Burn This! Why the D.O.K. Wheel Is Inaccurate

Misconceptions of Rigor and Depth of Knowledge

Seven misconceptions of rigor and depth of knowledge and they are:

- Misconception 1. All students can’t think deeply; all students shouldn’t need scaffolding to support deeper thinking.

- Misconception 2. Depth-of-knowledge levels should function as a taxonomy.

- Misconception 3. You can equate verb lists with depth-of-knowledge levels.

- Misconception 4. Depth of knowledge is about greater difficulty, more effort, or learning to do harder things.

- Misconception 5. You can assess all depth-of-knowledge levels with multiple-choice questions.

- Misconception 6. Higher order thinking always leads to deeper understanding.

- Misconception 7. Tasks requiring multiple steps, or the use of multiple or complex texts or resources, will lead to deeper thinking.

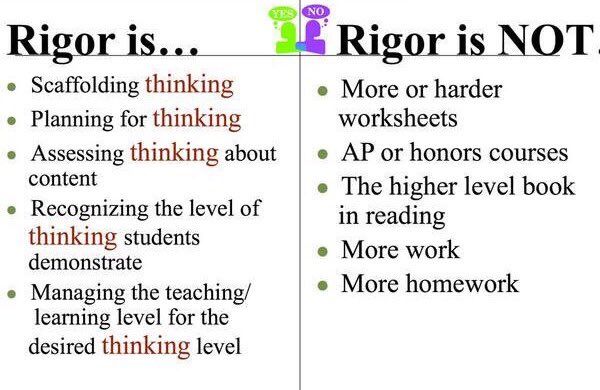

Karin Hess, author of Rigor by Design Not by Chance, mentions educators mistakenly grasp cognitive rigor to mean asking students to do more work, understand “harder” or more abstract content, or complete complex tasks independently. Hess beliefs this can cause inequity in what we expect of different students and how we teach them.

Let’s dispel misconceptions about rigor and depth of knowledge.

Misconception 1. All students can’t think deeply; all students shouldn’t need scaffolding to support deeper thinking.

Hess emphasizes that all students can think deeply. It is up to educators to find ways to scaffold learning so students can move from acquiring foundational skills to engaging in the deeper thinking that happens in the frontal lobe of the brain. Hess considers the thinking behind input plus one by Vygotsky. Hess says, “when a challenge is just beyond a student’s current level of independent mastery, social interaction and discourse can bridge the gaps in understanding, so learning can move forward.” Collaboration and discourse are some of the best ways for students to learn how to express and support their reasoning.

Misconception 2. Depth-of-knowledge levels should function as a taxonomy.

Both the original version and revised version of Bloom’s Taxonomy described it as a hierarchy of lower to higher thinking where higher thinking (analyze, evaluate, and create) is preferred over lower-level thinking (remember, understand, and apply).

As you can see

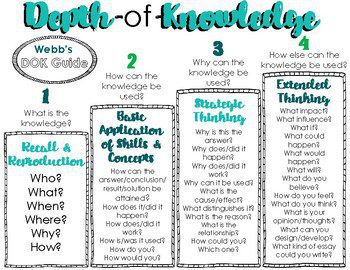

Depth of knowledge framework developed by Norman Web comprises of 4 levels:

- Level 1: Recall and Reproduction

- Level 2: Basic Skills of Concepts

- Level 3: Strategic thinking and reasoning

- Level 4: Extended Thinking

Hess explains that in reality Depth of Knowledge does not represent Taxonomy because DOK describes deeper and different ways of interacting with content where taxonomy devalues the role of foundational skills and conceptual understanding in laying the groundwork for deeper thinking and understanding.

Misconception 3. You can equate verb lists with depth-of-knowledge levels.

Hess calls the above wheel the “wheel of misfortunes” because it suggests that if you spin the wheel and pick a verb your students will instantly think deeply. This is not the case.

Hess explains verbs without content explains little about task complexity. Verbs and the wheel imply a connection does not exist.

Hess explains what we know about verbs as an indicator of task complexity:

- Verbs describe a type of thinking, not the depth of understanding or level of cognitive engagement with content.

- Verbs are generic, void of content. The same verb applies differently in different content areas. Analyzing a literary text requires the use of different schemas and thought processes than analyzing a work of art.

- Some of the same verbs appear at multiple levels of Bloom’s taxonomy; using them to determine the level of complexity of a test item or task is a subjective exercise.

- What comes after the verb determines the complexity of an assessment task or a learning activity.

Misconception 4. Depth of knowledge is about greater difficulty, more effort, or learning to do harder things.

Cognitive rigor is thinking flexibility and seeing multiple possibilities, approaches, or possible perspectives according to Hess. To understand ideas deeply and apply them broadly you need to uncover multiple perspectives or approaches to a problem. For example, debaters need to be flexible enough to use evidence on each side to argue for either the claim or counterclaim at a moment’s notice.

Hess explains that learning how to determine an author’s purpose, theme, or potential bias requires strategic thinking and decision making. Some tasks are hard to do, but they’re not cognitively rigorous. For example decoding words may be challenging at first, but with practice these tasks become easier.

Misconception 5. You can assess all depth-of-knowledge levels with multiple-choice questions.

You can assess all depth of knowledge levels with multiple choice questions that claim does not make sense. Hess says that “constructed-response questions, performance tasks, or extended projects are more suited for teaching and assessing the use of more complex tasks. To be clear, you can assess DOK 3 questions that focus on strategic thinking and reasoning with multiple-choice items.” Hess explains “However, when a student selects the “best” option, such as locating supporting text evidence for a stated theme, his or her response—whether correct or incorrect—provides little insight into how that student applied concepts and reasoning to arrive at the answer or whether the response is a result of guessing or, in the case of an absence of response, just inadvertently skipping the item completely.” Hess suggests multiple-choice questions work best for questions having only one correct response: DOK 1 and DOK 2 questions.

Misconception 6. Higher order thinking always leads to deeper understanding

Higher order thinking is associated with higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy—analyzing, evaluating, and creating. However, Hess says that many creative activities don’t lead to the deeper thinking needed to, say, investigate an essential question.

Hess emphasizes “Critical thinking activities begin by building a conceptual foundation (DOK 2) so that students can apply that understanding and transfer learning to new or more complex contexts (DOK 3 or 4). We see, therefore, that all levels of thinking have value; the goal of rigor by design is to be intentional about how to balance those levels throughout an “actionable” learning and assessment cycle.”

Misconception 7. Tasks requiring multiple steps, or the use of multiple or complex texts or resources, will lead to deeper thinking.

Many multistep tasks are actually learned routines. Not all multistep tasks are created equal. Hess explains these include applying skills and rules that are important to know but are still foundational (DOK 1). For example, think about long division. It can have many steps and can be hard to do at first, but it’s still a routine operation done the same way every time.

Hess points out all DOK Level 1 type of tasks students begin by building foundational knowledge; they might brainstorm what they know about the topic, learn new terms and vocabulary, or conduct a key word search. Then, DOK Level 2 makes connections among terms and ideas or examines cause and effect relationships and generate questions to investigate. Finally, DOK Level 3 or 4 gather data to help answer a broader, issue-based question.

Hess emphasizes that the steps of this process may begin as routine, but later on, they involve planning and strategic thinking, but the number of steps is not the determining factor of cognitive rigor.

The non-routine nature of how one step might lead to many decisions about other steps in the process deepens complexity and learning.

Hess beliefs “Students achieve deeper understanding when they dive into the concept and come away with new understandings and insights, making connections that can transfer to future learning.”

My Takeaway

I know I made mistakes with Rigor and Depth of Knowledge when I was a teacher. I did not know the important difference between rigor and depth of knowledge. Now that I have learned about the misconceptions, I wish I can go back and understand more about how to apply rigor and DOK in my teaching of English Language Learners. It would have made a difference in students’ learning.