How Does Project Based Learning Work?

Planning Steps of PBL

Three planning steps of PBL are Step 1: Plan with the End in Mind, Step 2: Plan the Assessments, and Step 3: Plan the Teaching and Learning.

These three planning steps are according to Ross Cooper and Erin Murphy, authors of the book Project Based Learning Real Questions. Real Answers. How to Unpack PBL and Inquiry.

In this blog, I will discuss how you structure a PBL experience from Cooper and Murphy in Chapter 2 of their book Project Based Learning Real Questions Real Answers. How to Unpack PBL and Inquiry.

Step 1: Plan with End in Mind

Cooper and Murphy suggest there are five potential starting points (none of which are mutually exclusive) when planning a PBL unit:

- Students: Find out what relates to the students, and use this as the basis for the project.

- Cool idea: Start with a cool idea that gets your students and/or you excited.

- A Process: Build your project around a process, such as design thinking or the engineering cycle.

- The end in mind: Establish what you want your students’ main takeaways (high impact takeaways) to be, and plan backwards from there.

- Academic Standards: Flip through your academic standards, looking for inspiration, which can come from standards that promote hands-on, minds-on, and interdisciplinary learning.

Cooper and Murphy emphasize that projects should connect to the standards no matter where you start, unless your students are engaged in Genius Hour.

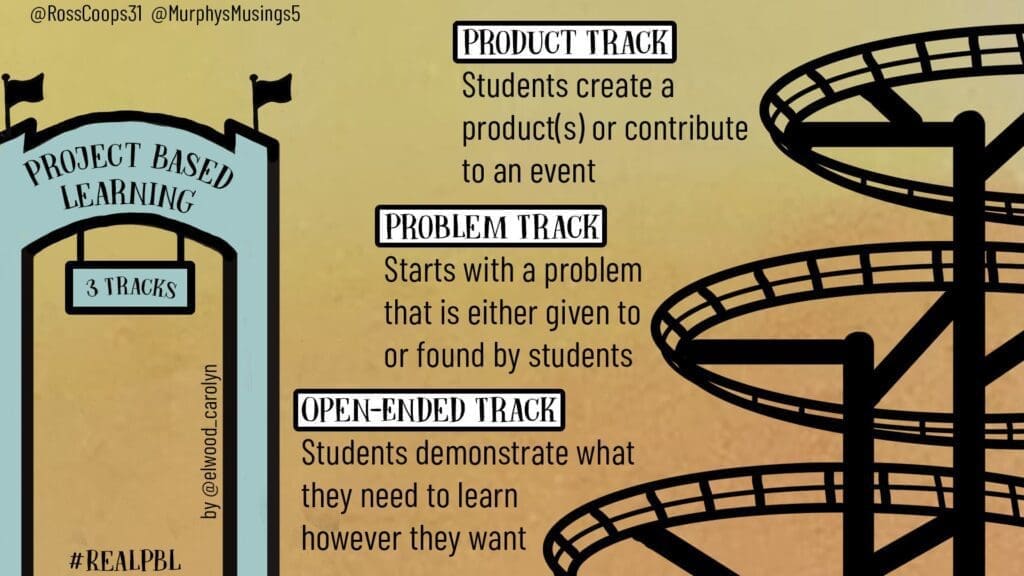

You can also rely on the three tracks to formulate ideas. The three tracks range from most restrictive to least restrictive. Cooper and Murphy suggest you think of these tracks as a gradual release of responsibility, starting with Product Track and ending with Open-Ended Track.

- Product Track: All students create a product(s) or contribute to an event, but there is flexibility in how they do it, so students can exercise their creativity to own the process.

- Problem Track: The project starts with a problem (usually a real-world problem) that either the teacher gives to students or students on their own. This approach is often called problem-based learning or challenge-based learning.

- Open-Ended Track: Present students with the project’s high impact takeaways, learning targets, and possibly an Umbrella Question, and ask them to show their knowledge however they would like, with only a little more directions.

You choose the track that fits best with your specific context for any project. Cooper and Murphy mention that one track isn’t necessarily better than another. You might use more than one track during a PBL Unit, like students debating an issue (Product Track) while solving a problem (Problem Track). But one track usually drives the unit.

Project Title

Cooper and Murphy suggest amplifying your project’s material with ready-made graphics and fonts if the title connects to something already exists (movie, band, video game).

Cooper and Murphy provide five generic titles, each followed by an alternative to which students might better relate:

- Movie Trailers; replaced with Coming Attractions (an authentic spin).

- The Pinball Project; replace with Pinball Wizard (from Tommy)

- Solar-Powered Cars; replace with Need for Speed: Solar Rollers (Like the video game)

- Farm to Table; replace with Green Cuisine (instead of Lean Cuisine).

- Endangered Animals; replaced with Angry Animals (instead of Angry Birds).

High Impact Content and Supporting Content

The select few academic standards that serve as the basis for the project are High Impact content. According to Cooper and Murphy, these standards require a deeper understanding of content (e.g., apply, understand, explain).

The ancillary standards that call for more surface level learning (e.g., define, recognize, identify) are Supporting Content. These standards support the High Impact Content. Cooper and Murphy suggest using standards (High Impact and/or supporting content) across multiple subject areas. This is to promote interdisciplinary learning. Plan with about eight total standards in mind – a number that can vary based on the project length.

Importance of Connecting Your Project to Standards

Cooper and Murphy emphasize that connecting your project to the standards means “you make the project the learning, as opposed to a fund activity after the “real learning” is finished.” Connecting your project to the standards helps students gain knowledge of those standards, and helps debunk the myth that PBL learning cannot prepare students for state tests.

Remember, “When we put standards in the hands of students, we do so in the form of learning targets, which are student friendly standards.”

High Impact Takeaways (also called enduring understandings)

Enduring understandings are students’ main takeaways from the project or the morals of the project. Cooper and Murphy remind us that when we generate High Impact Takeaways, ensure all your High Impact Content is accounted for. For example, Cooper and Murphy suggest you create one High Impact Takeaway for each piece of High Impact Content, or create one or two High Impact Takeaways that encompass all High Impact Content.

Cooper and Murphy also suggest considering these questions when crafting your High Impact Takeaways:

- Do the High Impact Takeaways promote inquiry, not rote memorization?

- Are the High Impact Takeaways in student-friendly language? Do they promote student ownership?

Importance of High Impact Takeaways

When you try to cover an entire topic with a project, you end up with surface level leaning. Cooper and Murphy believe that by planning with High Impact Takeaways in mind, you are asking yourself what your students’ main takeaways should be or what you want them to remember when they graduate. This way, it helps you focus on your project planning and teaching. It helps you present the project in a way that lets students learn deeper.

Cooper and Murphy suggest thinking about when to communicate the High Impact Takeaways to students, because when you put High Impact Takeaways in student-friendly language, you can make them available to students. However, High Impact Takeaways might still use academic language, so giving them too early could cause confusion and make it harder for them to get what they need from the project.

Umbrella Question (Essential Questions)

All the High Impact Takeaways wrapped into one question are called the Umbrella question. This serves as the Project Branding, according to Cooper and Murphy. Cooper and Murphy emphasize that there should be a straight line from the High Impact Content and Supporting Content (academic standards) to the High Impact Takeaways and finally to the Umbrella Question. Cooper and Murphy provide an example below, which illustrates this straight line with Take Action, a project in which students pursue civic processes to solve local problems while comparing their rights to the rights of citizens in historic contexts.

| High Impact Content and Supporting Content | High Impact Takeaways | Umbrella Question |

| High Impact Content: D2. Civ.2.9-12: Analyze the role of citizens in the U.S. political system, with attention to various theories of democracy, changes in American participation over time, and alternative models from other countries. D2. Civ.8.9-12: Evaluate social and political systems in different contexts, times, and places, that promote civic virtues and intact democratic principles. D2. His.4.9-12: Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras. Supporting Content: D1.9-12: Individually and with other students construct compelling questions and explain how a question reflects an adhering issue in the field. D.2.9-12: Explain points of agreement and disagreement experts have about interpretations and applications of disciplinary ideas and ideas associated with a compelling question. D1.5.9-12: Determine the sources that will help answer compelling and supporting questions, considering multiple points of view represented in the sources, the sources available, and the potential users of the sources. | Citizens pursue civic action to make change. The rights of citizens depend on historical and social contexts. | How can I pursue civic action to make change? How does civic action now compare to civic action of the past? |

Cooper and Murphy suggest Umbrella Question, which is the project’s branding towards the top of all project-related materials, so students can see how it relates to everything they are learning. Also during and at the end of the project, students make explicit connections between the learning and the Umbrella Questions. Have students write or blog after a project-related activity. Ask students about what they have learned and how it relates to the Umbrella Question.

When crafting your Umbrella Question, Cooper and Murphy suggest considering these three questions:

- Does the Umbrella Question promote inquiry, not rote memorization? During a project, it should feel as if students are interrogating the Umbrella Question.

- Will the Umbrella Question elicit multiple responses, not one definitive answer? Is it Googleable?

- Has the Umbrella Question been written in a short, compact, and conversational way, almost as if it could be repeated like a mantra?

Cooper and Murphy illustrate how we can derive a project’s Umbrella Question from a project’s High Impact Takeaway:

| High Impact Takeaways | Umbrella Questions |

| Claims and counterclaims use evidence and organization to be effective. | What is an effective argument? |

| We read to learn new information and make decisions. | Why do we read? |

| Properties of operations can be used to multiply and divide numbers. | Which properties matter the most? |

| Fossils document the history of life forms. | How does a fossil tell its story? |

| Our government has powers, responsibilities, and limits that change and are contested. | Who has power? |

High Impact Takeaways and Umbrella Questions are general, because they focus on what the student has learned, rather than the details of their project. Using this language can help students use what they’ve learned in different scenarios outside the project. This process is known as transfer of learning. Cooper and Murphy note the driving question is the subcategory of Umbrella Question. What an Umbrella Question is sometimes referred to when it is more project specific (e.g., “How might we redesign our classroom?”). Other than this, one difference, a driving question, should be crafted and used in much of the same way as an Umbrella Question.

Learning Targets

Cooper and Murphy suggest three tips to consider when converting standards to learning targets:

- If a standard has multiple independent actions (e.g., I can identify a dog and a cat), split into multiple learning targets (e.g., I can identify a dog). (I can identify a cat).

- Make sure all learning targets are student-friendly, because you ultimately want students to leverage these targets to drive their own learning through self-assessment. Most current standards are already student-friendly, aside from academic language. So, much like High Impact Takeaways, ensure students are not confused or overwhelmed when given learning targets. Building background knowledge can help, as can being intentional regarding when you communicate the targets.

- To promote inquiry, present each learning target as a question (“Can I…?” instead of “I can…”)

Cooper and Murphy emphasize that students should achieve their learning targets. Learning targets should serve as the basis for a project’s assessment (step 2) and instruction (step3).

Step 2: Plan The Assessment

Cooper and Murphy use the Progress Assessment Tool (simplify version of a rubric), to show the intentionality with which assessment (Step 2) connects to the desired results (Step 1).

Cooper and Murphy designed the Progress Assessment Tool, a three column “rubric”, to give students toward the start of a project. See Below Chart.

| Learning Targets | Success Criteria | Feedback |

| I can analyze the role of citizens in U.S. political systems. | The explanation or interpretation shows a close examination of the rights of a citizen. | |

| I can evaluate social and political systems in different contexts, times, and places. | A distinction is made between various political systems and civil rights across historic contexts. An opinion is stated regarding the effectiveness of various political systems. | |

| I can analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras. | Influential factors relevant to the historic context are identified. The impact of the factors on the perspectives of people is examined and explained. | |

| I can construct a compelling question. | The project identifies a relevant problem. The problem is reasonably approachable. | |

| I can explain varying perspectives regarding a compelling question. | Varying perspectives from multiple sources are presented and explained. | |

| I can determine the sources that will help answer compelling questions. | Primary and secondary sources are used to inform the work. , content is collected from various sources: database, official websites, print, etc. |

Left column: The Project Learning Targets

You are assessing students on what you want them to learn based on how well they follow the project directions, a practice that promotes compliance. Your assessment tool looks like project directions are regurgitated in another format; you need to redo it.

Middle column: Each learning target’s success criteria

Success criteria should be medium agnostic if you want students to have flexibility in how they show their learning. Cooper and Murphy suggest you refrain from mentioning specific products, technologies, or tasks. The litmus test is to ask. Students can work with the teacher to construct success criteria, rather than simply give them. Cooper and Murphy did this through the analysis of exemplars (e.g., students analyzing various narrative essay introductions to determine their quality features).

Right column: Where feedback is given about each target.

Cooper and Murphy strongly recommend creating and distributing a digital version of the Progress Assessment Tool, potentially through Google Docs or Google Classrooms. This way, it is available to everyone, and because it is digital, the cells/boxes will expand as we type into them.

Every student receives a copy for an individual project. Cooper and Murphy suggest you think about group-assess versus individually assess? Sometimes group projects have a combination of the two.

Each group gets a Progress Assessment Tool, and so does each individual. On the group copy, give feedback on the group learning targets, and on the individual copy, give feedback on the individual learning targets. If you can individually assess students on all targets, every student gets their own Progress Assessment Tool. If every target is group-assessed, do one copy per group. If a grade is necessary, try to avoid group grades.

Cooper and Murphy put out a disclaimer that you can adapt these ideas about Progress Assessment Tool use in the classroom to work with a more traditional rubric or similar assessment tool.

Step 3: Plan the Teaching and Learning

Cooper and Murphy focus on reflection and publishing in Step 3 of Plan the Teaching and Learning.

Cooper and Murphy note educators fail to realize that reflection can help students show higher-order thinking. Reflection can take place wherever and whenever. It helps educators revise and refine our work.

There are two categories to consider why we have students reflect during PBL:

First Category is non-evaluative. This is when trying to get students to think critically about their work. You can use prompts and think about fading out those prompts to promote independence (gradual release). Cooper and Murphy provide these examples:

- What additional questions do you have about this topic?

- What strengths can you identify in your work?

- What are you most proud of?

- How could you improve your work?

- What would you do differently next time?

- What connections can you make between now and your past experience?

- How has this new learning changed your thinking?

Second category is more evaluative, because it connects to specific learning targets. This could fall under step 2 instead of step 3. Cooper and Murphy suggest using prompts to draw out information from students when you want to determine whether they have learned the material. Cooper and Murphy suggest these reflections for assessment purposes and possibly grades:

Example 1: Students are engineering solar-powered cars, and you want to make sure students understand how their cars harness the sun’s power to propel (or not propel) their vehicles. Ask them: Using academic vocabulary, explain all the steps you had to take to transform the sun’s energy into motion. If your car is not working, include when and why the breakdown occurred, and what you will do to fix it.

Example 2: Students are tasked with designing their own businesses, which they will pitch to local entrepreneurs for feedback. You want to make sure students understand what a quality pitch involves. After each student’s first pitch, ask: Reflect upon your pitch, one part at a time.

Based on the feedback you received, what will you change when you pitch again?

Example 3: Students are tasked with finding and solving a school-wide problem. You want to ensure students understand empathy and how they must consider all stakeholders when tackling their problem. Towards the middle of the project, ask: One stakeholder at a time, explain your strategies for addressing their wants, needs, and perspectives.

Cooper and Murphy suggest students should reflect in multiple ways, such as written reflections, blogging, videos, or discussions. During and after the reflection process, make time for them to improve on their work. This is for both categories.

Publishing

Cooper and Murphy note publishing does not just come at the end of a project. It should mimic closely what we do as adults. Cooper and Murphy state in their book Hacking Project Based Learning:

“Students may make their work public throughout a project to: obtain audience feedback, promote their work, provide self-motivation, or because multiple steps are involved, and they have chosen to publish after each one.”

Cooper and Murphy suggest three ways to use publishing as part of Project Based Learning, and they are not mutually exclusive:

Example 1: Use publishing to document the process. Have students continuously film their work in progress, and every Friday ask them to publish a more polished video that documents their process (which helps them obtain feedback and reflect on their work).

Example 2: Use publishing as the project’s final product. If students raise awareness for an endangered animal, like the bald eagle, ask them to publish an original song toward the end of the project, and then promote it via social media to raise awareness.

Example 3: Use publishing for sharing. If students use the school’s outdoor classroom to grow vegetables and explore farm to table, ask them to create presentations to share what they have learned with other students, families, and outside experts, possibly at a community exhibition or other event.

Cooper and Murphy want educators to approach the publishing platform with intentionality. Cooper and Murphy do not want educators to cry “differentiation” or “student choice” when students may present what they have learned, such as via PowerPoint, Prezi, or infographic. Cooper and Murphy emphasize, “Student choice needs to be more than letting students decide where they can copy and paste their work.”

Let students decide on their publishing platform, with flexibility to change along the way during the project. Rather than choices being made based on what is cool or easily accessible, ask students to make their choices based on what they are trying to accomplish. Cooper and Murphy believe the true differentiation occurs as students or groups of students carve out their own paths to meet their learning goals. Cooper and Murphy emphasize, “While technologies and mediums are part of this process, they are not the differentiation in and of themselves.”

Cooper and Murphy’s Final Thoughts

Here are two important thoughts to consider from Cooper and Murphy:

The myth of educators sitting around the table “perfectly planning” their PBL unit, delivering it to students, and then hoping for the best. This is not the way to go. The problem is that when we take this approach to planning, we leave out our most valuable stakeholders, our students.

Please give your students a voice during the learning and planning process. If you are transitioning to project-based learning, communicate to students (and possibly families) how your instruction is changing and why, while continuously asking for their feedback. This way everyone is moving toward Project Based Learning, rather than something “done to students.”