Questions to Consider When Choosing Scaffolding Strategies

Karin Hess, author of the article ‘How to be Strategic with Scaffolding Strategies’, wants educators to consider this question when choosing a scaffolding strategy:

- Why did I choose this strategy?

- Does it match my learning target? and

- How will it optimize learning for some or all of my students?

Previous Post

3 Myths about Scaffolding

Hess shares some ideas about making good choices, but first Hess wants to clear up 3 common myths about scaffolding:

Myth #1: Scaffolding is the Same as Differentiation

Many teachers – and even some educational resources – often mix scaffolding with differentiation, but they are distinct. To help remember the difference, you can think of scaffolding as providing the necessary support to complete a task, while differentiation offers students various options regarding the tasks they can undertake.

When instruction is differentiated, students select from various assignments that are often similar in difficulty. I first intentionally used differentiation during my time teaching middle school. I developed assignment menus that catered to different content (varying texts, materials, scenarios, or subjects), the processes involved (levels of engagement with the material, whether working solo or in pairs, etc.), and the products that students created to demonstrate their understanding. Tools like choice boards, menus, and activity stations are frequently employed throughout a unit to present optional tasks for students.

On the other hand, scaffolding strategies are designed to help each student effectively engage with grade-level content, complete assignments ranging from basic to advanced, and build their confidence and independence as learners.

Myth #2: Scaffolding is always temporary

In fact, many scaffolding techniques—like dividing a task into manageable pieces or collaboratively creating an anchor chart to enhance understanding—can be applied later, even as tasks become more complex. Scaffolds aren’t just for students who need extra help. Even top-performing adults break intricate tasks into smaller segments and rely on models and peer feedback to better grasp new concepts. Think of it this way: a painter

always utilizes some form of scaffolding when working on a ceiling.

Myth 3: Scaffolding is used to change the intended Rigor

A scaffolding approach can lighten the cognitive load on a learner’s working memory during educational activities, without altering the challenge level of the task.

For example, when a complex text is read aloud or illustrated as a graphic novel, students are relieved from the need to fully use their working memory to decipher unfamiliar words for understanding the text’s meaning. Instead, they might take sketch notes while listening, capturing essential ideas to facilitate later summarization, discussion, or explanation of more intricate concepts.

While decoding skills are vital, the primary focus of this learning activity isn’t solely on decoding words. Similarly, when a student uses a calculator to perform calculations with large numbers or decimals, they can verify their estimates without the cognitive burden of manually calculating the same operations.

Understanding the learning objectives helps educators identify the most suitable scaffolds for the lesson and specific students—essentially, placing the scaffolding activity in their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Scaffolding is aimed at ensuring that even if a student encounters difficulties, those challenges are constructive.

Consider scaffolding as a bridge that can either (a) enhance content accessibility (such as “chunking” texts, conducting focused discussions, or building background knowledge) or (b) simplify multi-step tasks (like

collaborative data collection or breaking tasks into smaller, manageable parts with checkpoints).

Determining the Right Time for Scaffolding

Educators can benefit from considering three main areas of support that help students build the skills necessary for tackling more complex tasks or grasping difficult concepts:

- enhancing content understanding,

- improving executive function, and

- fostering language and vocabulary skills.

Effective scaffolding at one Depth of Knowledge (DOK) level typically helps students progress to the subsequent DOK level. Below, Hess outlines various strategies for each DOK Level tailored to different teaching goals. (For a

comprehensive collection of strategies, be sure to download Karin’s PDF.)

Scaffolding Purpose 1: Enhancing Understanding and Linking to Key Concepts

Various techniques aimed at enriching learning can easily emerge from activities focused on improving language abilities or fostering executive function. For example, collaborating with students to create an anchor chart outlining the steps for tackling a non-routine math problem not only bolsters executive functioning, but also serves as a useful reference. This chart can remind students of each step as they approach new challenges.

Scaffolding Techniques to Enhance Learning Across Various DOK Levels

DOK 1 – The “DAILY 10” Playlist

The role of prior knowledge in improving reading comprehension and developing schema is crucial. To implement this technique, create a playlist featuring at least six short printed and non-printed materials on a subject (like images, political cartoons, articles, or relevant websites tied to social studies or a science unit) for

students at the week’s start.

Each day, for a maximum of ten minutes, students—either individually or in small groups—select one resource to read or listen to and jot down some notes. These notes are not graded. Encourage class discussions and journal entries to link this expanding background knowledge to the current unit of study.

DOK 3 – Carousel Feedback

This approach reframes carousel brainstorming, where small groups rotate through different stations, brainstorming ideas on various subtopics. They record their thoughts on large chart papers for the next group to read and contribute to.

The teacher sets up 4 or 5 large posters, each featuring a unique question prompt or problem-solving task. Students are grouped in a diverse arrangement, each group using a different colored marker for their answers. They start by reading the problem at their table and working on the chart paper to find a solution.

After a few minutes (before they complete their task), the teacher signals for time, and the groups rotate to tackle a new problem. Upon arrival, they review the previous group’s work and discuss it among themselves. They then determine whether the last group’s solution was correct and use a new color marker to either continue solving the problem if it was right or to make adjustments if they spot an error. If corrections are needed, they add a note explaining the mistake and the rationale for the correction.

When time is called again, the groups rotate for a third time, repeating the checking and justification process as before. In the final round of rotations, the groups create a justification for their solution, relying on calculations and notes provided by other teams. This carousel approach fosters meaningful discussions and encourages collaborative reasoning backed by evidence.

Purpose of Scaffolding 2: Enhancing Executive Function and Skill Application

Students who struggle with executive function often find it challenging to stay focused and engaged in dealing with long texts and complex tasks. This skill set also plays a crucial role in goal setting, monitoring progress, and fostering a positive self-image as learners. Executive functions encompass various skills

that help students start, track, and complete intricate multi-step projects.

Scaffolding strategies can help in several areas:

Initiation – The ability to kick off a task or activity while generating ideas,

responses, or finding solutions (e.g., collaborative brainstorming sessions).

Working Memory – The ability to retain information for engaging with longer

texts (e.g., breaking texts into manageable chunks).

Planning and Organization – The skill to handle both current and future tasks

demands (e.g., maintaining learning logs).

Self-Monitoring – The capacity to assess one’s own performance and compare it

to established standards or expectations (e.g., through conference discussions).

Supportive Strategies for Executive Function at Varying DOK Levels

DOK 2: A Card Pyramid for Information Summarization

The card pyramid technique uses numbered sticky notes or index cards to dismantle information from a text. Ideally, partners collaborate to construct the pyramid, taking turns to verbally summarize their findings, before penning down a written summary.

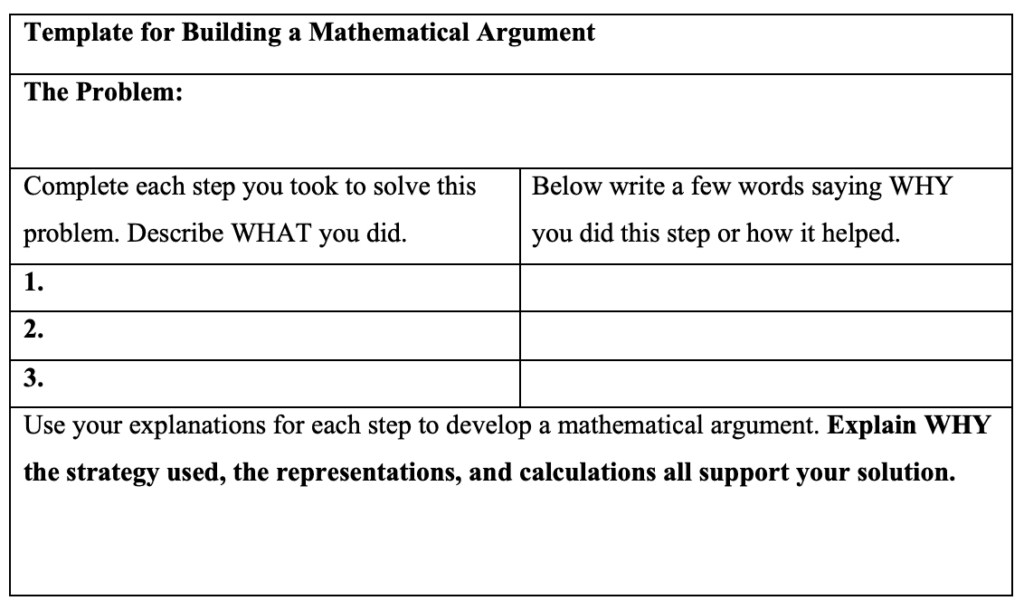

DOK 3: Crafting a Mathematical Argument

Teaching how to create a mathematical argument can be as challenging as learning it. In this approach, partners split their paper vertically. On the left side, students methodically work through the steps to solve the problem, while on the right, they articulate the reasoning behind each step or explain how it works.

contributed to their solution (e.g., my diagram illustrates the division of the candy bar; I’ve labeled each fractional part to clarify…). This scaffolding method is beneficial, as it deconstructs the path to the solution, allowing for a more thoughtful explanation of the reasoning behind each action.

Scaffolding Purpose 3: Nurturing Language and Vocabulary Growth

Developing vocabulary and language skills is crucial for understanding across all subjects. One effective strategy for enhancing vocabulary is to emphasize and reinforce the key language necessary for learning in each content area. Teachers can informally boost language development by using visuals and tangible models to activate prior knowledge, color-coding to highlight significance or differences (like anchor charts, sentence stems, or paragraph frames for multi-digit number place value), facilitating meaningful discussions, and

demonstrating their thought processes aloud.

Using multi-sensory techniques can help students develop their language skills. However, it’s important to avoid overwhelming them with too many methods simultaneously, or relying on strategies that don’t easily carry over to future learning. A charming visual of a pumpkin or cookie may not effectively help students understand paragraph or essay writing compared to a structured anchor chart or a color-coded paragraph frame with clear visual cues.

Hess enjoys introducing TBEAR through texts familiar to students, such as fairy tales or pieces they’ve read in class before. Teachers at all grade levels have used or modified TBEAR, and have found it particularly effective for students struggling with language proficiency. In both whole-class settings and partner work, students can use TBEAR to help them find text evidence and prepare for discussions or writing assignments. For example, middle school teachers I’ve collaborated with had students develop and display anchor charts

for important math vocabulary after analyzing these words through TBEAR.

TBEAR smoothly supports students in progressing from DOK level 1 to levels 2, 3, or 4, and it’s easy to recall what each letter represents:

T: Create a Topic sentence/Thesis statement/or claim (DOK 1); or define a vocabulary Term or concept.

B: Succinctly summarize the text to act as a bridge to your evidence (DOK 2); or rephrase the meaning in your own words.

E: Find text Evidence/Examples (DOK 2); or offer both examples and non-examples when defining specific terms.

A: Analyze each example or piece of text evidence; include additional details to explain why the evidence backs up your thesis/claim (DOK 3).

R: Share a key takeaway (DOK 1 or 2) or a reflection that might extend from DOK 3 to DOK 4, such as links to the world, personal experiences, or ties to additional resources.

Support for Everyone

True equity starts with the understanding that all students can and should progress beyond memorizing routines and gaining superficial knowledge in a subject. This is particularly important for students with learning disabilities and those who speak multiple languages.

Research indicates every student benefits from daily chances to express their creativity, interpret information and ideas, pose questions, engage in research, and develop their own insights through meaningful discussions.

For Review