Effective SEL Teaching Practices

In their book, Building Blocks for Social-Emotional Learning, Tracy A. Hulen and Ann-Bailey Lipsett introduce ten SEL instructional practices you can use to teach and integrate social-emotional skills into academic and social settings throughout the school day:

- Transitions

- Student goal setting

- SEL daily routines

- Picture book read-aloud and reading comprehension strategies

- Social-emotional learning during play

- SEL-focused partner or group games

- SEL journal writing

- SEL projects

- Teachable moments

- SEL classroom learning centers and menus

I will show some of the SEL Teaching Practices in this blog. If you would like more information, you can read Building Blocks for Social-Emotional Learning. This book has been nominated for Indie award according to Solution Tree publishing company.

Hulen and Lipsett use Vignette: Teaching and supporting Daniel throughout the SEL

Backgroud Information

From the Building Block of Social Emotional Learning book, authors Tracy A. Hulen and Ann-Bailey Lipsett provided Vignette: The Story of Daniel:

Maria Smith, Daniel’s teacher, sat alone in her classroom after school, reflecting on her day. She wondered how she was supposed to meet Daniel’s needs while also teaching him reading, writing, and mathematics and keeping the other students safe. Rightly so, she wondered how she could be proactive in changing his behaviors so that she was not left in near-dangerous situations.

To begin changing Daniel’s behaviors, Maria needs to look at his actions as more than simply behaviors but instead as clues into Daniel’s unique, individual profile. She needs to identify what skills he may be missing to comfortably access learning. Why can’t Daniel lose a game without melting down? Why does independent work make him so angry, yet he can complete the same work if he is sitting next to the teacher? Why can he appear to be perfectly happy and then suddenly erupt with anger and violence? Why can’t Daniel sit still during focus lessons, remember to raise his hand when he has a question, and wait in line without bumping into the person in front of him?

What’s going on with Daniel and other students like him, who seem to have something keeping them from moving forward?

Hulen and Lipsset use the example of our fictitious student named Daniel and his teacher Maria to help you define what SEL is, understand the importance of teaching it, learn how to support students’ emotional regulation, teach emotional regulation strategies, and discover students’ neurological development and its relationship to behaviors.

In reflecting on Daniel’s abilities and needs, his teacher realized he is still developing a strong sense of self. Daniel is yet not able to identify what makes him happy, sad, or frustrated, although he knows the vocabulary words. Before Maria can expect him to stay calm in her classroom, she recognizes that she will first need to help him understand when he is getting frustrated, without getting overly frustrated herself. “How am I ever going to have time to give Daniel those skills on top of everything else I must do?” she wondered. “There must be a better way to reach Daniel and all the other students.”

Instructional practices.

Maria found herself thinking about Daniel and students like him often. He had so much potential, and yet so often had difficulty participating in her lessons. She knew he should be doing better in school than he was, but he barely produced work due to his emotional outbursts. She didn’t feel like the solution was to create an individualized program for Daniel, and she knew she couldn’t just send him to the office every time he was upset. In fact, there were too many students like Daniel who needed her to shift her own teaching practices. After an episode, Daniel could label exactly what he should do next time. He could identify emotions and talk about using calm-down strategies, but he couldn’t seem to bring himself to use them in the moment. There had to be a better way to support Daniel’s social-emotional learning, along with all students in her classroom, throughout the regular school day.

Transitions

Vignette: Teaching and supporting Daniel

It was time for the reading workshop to end, and Maria dreaded stopping the class from their work to ask them to clean up. Transitions—or moving from one activity to another as a class—were difficult for all the students in her class, but particularly Daniel. Ending one activity and moving to a new one always seemed to create power struggles and cause the class to lose instructional time. What’s more, she felt like these moments were wasted opportunities. She was interacting with the students during this time, but more like a traffic cop—correcting their behavior, monitoring their safety, and directing them where to go—and less like a teacher. When she thought about how to adapt her school day to support Daniel and her other students with “big feelings,” she wondered about transitions. Could these be opportunities to change her interactions from simply being a behavior monitor to meaningful teaching? Would that make transitions smoother for the whole class?

Maria could use purposeful transitions to change her interactions with students to meaningful teaching.

Authors suggest purposeful transition because it allows the learning and practicing of skills and concepts, and serves as a useful management strategy, engaging students in a task and limiting the opportunity for classroom behavior issues to arise.

Teachers can begin to incorporate purposeful transitions around social-emotional learning by using transitional time to have students learn and practice SEL skills. This is a great way to teach SEL and integrate academics and SEL learning. It also allows teachers to interact with students in a more meaningful way during these short moments, rather than simply monitoring behavior. Authors emphasize that it directly teaches students what tools they can use to make these moments of transition less stressful.

Helen and Lipsett suggest ways to integrate SEL learning into transitions:

- Label how students feel about changing subjects by modeling. Using a think-aloud strategy, the teacher can state ‘It’s time to clean up. I’m so frustrated right now, because I want to keep reading with you all. I don’t want us to clean up, but it’s time for lunch. I am going to take two deep breaths and think about what I need to do to prepare for lunch. Breathe with me —- one, two —-‘

- Guided Practice. Kindergarten students counting backwards as they transition from learning station to learning station in their mathematics workshop. The teacher can have students use deep breathing, along with counting back from five.

- Blowing out candles self-regulation strategy. Counting-backward strategy where students pretend their five fingers are five candles, and use deep, slow, long breaths to blow out a candle and count back with each breath from five to zero. Deep breathing slows down our body responses, lowers our cortisol levels, and moves us away from our fight, flight, or freeze response so that we can again access our decision-making abilities in our prefrontal cortex (Ma et al., 2017).

Authors believe these breathing strategies support the development of SEL building block component 4 (emotional regulation) and cognitive executive functioning skills, and give students a tool to control their own emotional responses.

Student Goal Setting

Vignette: Teaching and supporting Daniel

Maria watched as Daniel and Maggie cleaned up from their reading center using the breathing exercises she was leading the class through during the transition. She smiled as the two laughed together at blowing out their finger-candles. Later in the day, while Daniel worked on his writing, he threw his paper across the room. “It’s not perfect!” he cried. Maria went to him and suggested he try breathing, but he just put his head down and sobbed. “I can’t! I try to be perfect and not get upset, and everyone else is perfect, and I just can’t!”

Reflecting on this made Maria realize that Daniel is putting a lot of pressure on himself to “be perfect”, but he does not necessarily know what this means. It seems like an unattainable goal. To even learn to use these self-regulation strategies, Daniel must begin to understand how to set a goal and achieve it through small steps, so that he can celebrate his successes along the way. Come to think of it, all students benefit from goal setting, Maria thought. What if we incorporate goal setting into our classroom?

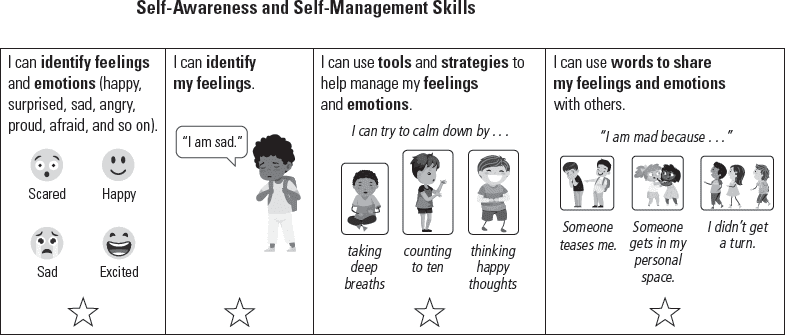

Maria is right about students benefiting from goal setting. Teachers can use “I can” statements from essential SEL standards and use them for student goal setting. Authors note that when students know their learning targets, they are not only more likely to learn the skill, but also to use and practice a cognitive executive functioning skill (namely, goal setting) needed for academic learning, and something that is a lifelong skill.

It is important to remember that goal setting should require shared ownership between the teacher and the student. Teacher needs to facilitate the process, but it is equally important for the student to take personal ownership in the act of goal setting. Student goal setting becomes meaningless if the student is not part of the process.

So, how can teachers help facilitate social-emotional goal setting so that it is meaningful and manageable for teachers and students?

Hulen and Lipsett suggest the goal card in figure 4.4. These are four essential learning targets that progress and build on one another. They could be four core essential learning targets at kindergarten that students focus on for the entire school year, or they could be goals to focus on for one to two months, such that all lessons connect and build on these four essential learning targets.

Student goal setting can also be more individualized for students.

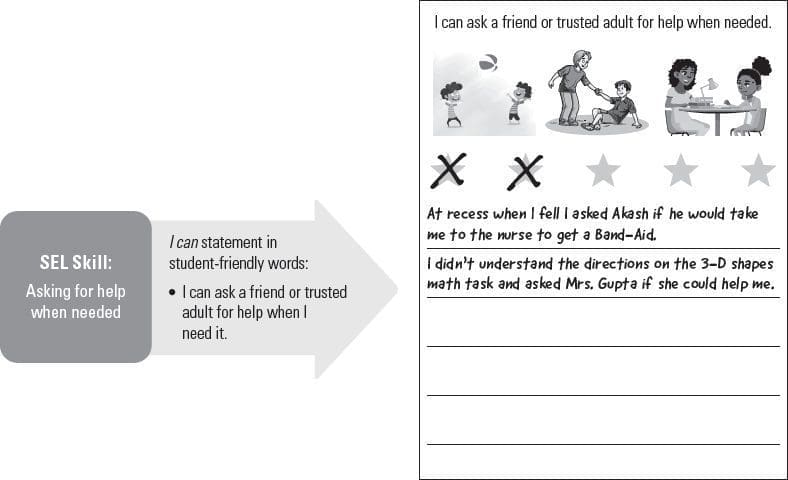

Individual SEL student goal card.

Teacher used an assessment tool to determine that a student struggled to keep her hands and feet to herself at the carpet, in line, and at recess. The teacher created a personal goal card for the student and conferenced with her regarding its use and purpose. The teacher then decided the student’s goal card would be taped onto her desk, so it was a consistent visual reminder. When the student kept her hands and feet to herself at the carpet, in line, and at recess, the teacher would check in with the student and give positive verbal praise. The student would then be given a star sticker to be put on the goal card. When the student modeled the behavior five times, the goal card would be completed and sent home for the student to share with her parents. The goal card also became the teacher’s informal data collection tool, serving as a record that demonstration of the skill was observed.

Reflective student goal card—asking for help.

The SEL skill is about asking for help when needed. The team used student-friendly language and changed the wording to ask for help from a friend or trusted adult when needed.

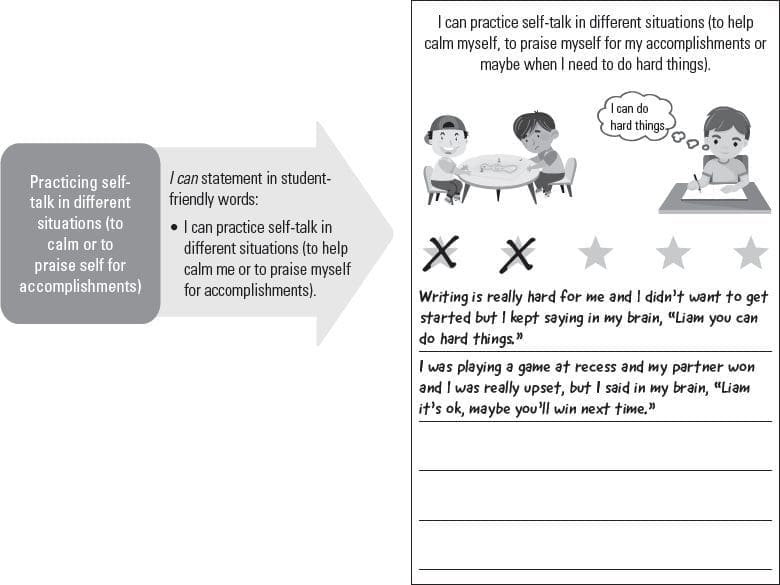

Reflective student goal card—practicing self-talk.

Some students may consistently already ask for help when needed, while others may struggle in this area. These students may get a different student goal card that better fits their needs, such as the example in Reflective student goal card—practicing self-talk.

SEL Daily Routines

Teachers can create SEL daily routines or incorporate SEL into any existing routines part of the regular school day. One routine the authors discuss is morning routines. Maria’s class started with:

Daniel and Maggie dragged themselves into their classroom, looking rather glum. Maria greeted them happily and reminded them to go through their daily morning routine. She was glad they seemed to become such good friends. She was worried about how today would go for them based on their emotions this morning. She had been noticing that she could predict how the day would go for both based on how their mornings went. On days when one of them seemed disorganized and dysregulated, and had difficulty remembering the classroom routines, she knew the rest of the day would be like this as well. Maria had come to realize that on days when they came in so glumly, Daniel could end up with negative thinking that would lead to an outburst if she did not step in. Luckily, Maria thought we have a morning meeting to help us mentally transition into our school day and organize ourselves for the day. Maria had begun increasing social-emotional learning into her morning meeting. It was saving her time, changing the tone of her school day, and teaching vocabulary she could refer back to when students had big emotions.

Morning meeting routine allows students within each classroom to develop a community, connect with the teacher and their peers, share their thoughts and perspectives, and review the daily routine. Authors believe this one routine promotes the development of SEL building block components 1 (self-awareness), 2 (reciprocal engagement), 3 (social awareness), and 4 (emotional regulation) and executive functioning. Morning meetings provide a safe, comfortable start for each school day (Dabbs, 2017; Williams, 2011).

The following shows what this might look like in the classroom and how it could play out.

Maria gathered her class on the rug they use for a meeting area each day. The students sat around the edge of the rug, facing inward. “Good morning!” Maria announced. “It’s wonderful to see you today! Let’s begin our greeting. Today we’ll say hello in Spanish—Hola! When it is your turn to greet your friend, turn your body all the way around so you are knee to knee. Look your friend in the eyes and smile so they feel that you are happy to see them. In a big voice, greet your friend by using their name.” Maria’s directions reminded the students of the specific social behaviors she expected them to use during this time. “Who can show me what that looks like?”

Johnny raised his hand, and Maria asked him to greet his neighbor. As the greeting spread around the circle, Maria smiled at the students and provided gentle reminders to make eye contact, turn, and use their friendly voices. When the greeting reached everyone, she addressed the class. “Wonderful. This week we have been talking about identifying our emotions. Give me a quick thumbs-up if you noticed you felt happy when your friend looked at you and smiled.” This whole-group response encouraged everyone to participate, without taking time to listen to individual answers. Maria kept the pace of her morning meeting going. “Turn your bodies to see today’s message,” she told the class. Because this is a practice, the class quickly moved to their spots on the rug where they could see the message.

“Dear Fantastic First Graders! Today is Tuesday, October 28th, 2019. Today we had PE and music. I noticed I have two feelings about book character day on Friday. I am excited to share my costume with you, but I am also a little nervous that I’ll wear a costume to school. Who else feels that way?

Have a great day!

Love, Mrs. Smith.”

The class read the message two times. As they read, Maria changed her voice to reflect how she felt with each emotional word. “I wonder if anyone else is feeling this way about Friday. Without talking, put up two fingers in front of your chest if you are feeling two feelings about Friday. Put up one finger if you are feeling one feeling, and three if you have three feelings!” She waited while the students thought, and then shared their fingers.

“Johnny, put your fingers in front of your chest, don’t wave them in the air! Wow—I see some people just have one feeling, while others have two or three! We have a lot of feelings in this room! It is normal to feel two or more feelings about one event. It feels mixed up inside, but events can make us feel many different things. Time for our game. Who wants to lead Simon Says?”

After the game, Maria again asked for a show of fingers of how many emotions they felt during the game. “Simon Says always makes me nervous! I’m worried that I’ll miss something,” she shared. “Did anyone else have a different feeling?” She chose one student to share, and then moved on to the sharing portion of the morning meeting.

Picture Book Read-Aloud and Reading Comprehension Strategy

Vignette: Teaching and supporting Daniel

With an extra five minutes to spare before lunch, Maria grabbed the class’s favorite book—The Pigeon Has to Go to School! by Mo Willems (2019). It’s such a silly book, Maria thought, but the students seem to connect with it. Especially when I act like a pigeon—and ask the class to do the same. It’s funny, she thought. Daniel and Maggie are often the most engaged during read-aloud, especially when the characters have big emotions. I wonder how I can use these to further teach and practice our SEL skills?

Authors believe storybook read-aloud provides multiple benefits to classroom communities.

- They create a shared experience and language as a class listens and responds to a story together.

- Stories can provide a narrative for academic content, illustrate a concept, or simply provide a quiet time for students to become immersed in language.

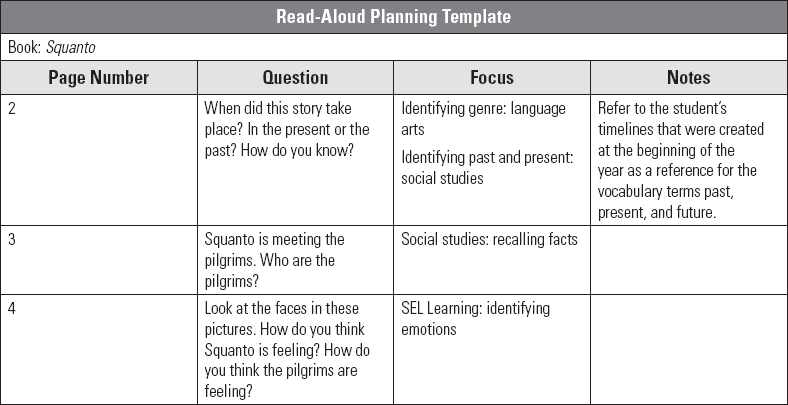

Yet during a busy classroom day, read-aloud can often be overlooked or under-planned for, especially in the upper elementary grades. As teachers, we grab a read-aloud when there is a surprise free ten minutes in the day, or when building interest and background in a new concept. Well-planned, interactive read-aloud increase students’ abilities to interact with the text, engage with their teacher and the concepts the book presents, and heighten deeper-level thinking (van Druten-Frietman, Strating, Denessen, & Verhoeven, 2016; see figure 4.12).

Interactive Read Aloud Template Link

Authors believe read-aloud supports social-emotional learning in two specific ways.

- First, books can be intentionally chosen to specifically teach or enhance a social-emotional concept. When the class is working on identifying emotions and using calming strategies (SEL building block 4: emotional regulation), teachers can read books like When Sophie Gets Angry—Really, Really Angry by Molly Bang (1999) to illustrate the concept. Elephant and Piggie books, by Mo Willems, are excellent for encouraging students to identify emotions within a text. In these books, the characters become overcome with emotions easy to identify through the illustrations and dramatic words. By the end of the book, the characters are again calm, providing classrooms with the opportunity to discuss how the characters used calm-down strategies before resolving their problem.

- Teachers can include social-emotional questioning into the read-aloud they use for their academic areas. If the class learns about fractions and fair shares, they may read The Cookie Fiasco by Dan Santat (2016). In addition to planning interactive questions to encourage the students’ problem solving and deeper-level mathematics thinking, teachers can embed social-emotional questioning here. In this story, four friends panic because they have three cookies and cannot figure out how to fairly share the cookies. While discussing the mathematics parts of the story, students can also track the characters’ emotions as the story progresses. As the class notices how the characters’ emotions change with each event, they can connect the events of the story that cause emotional responses (SEL building block component 4: emotional regulation and executive functioning). This will build heightened interest in how the characters solve the problem (using mathematics). In most fiction stories, the characters’ decisions and actions are driven by their emotions. Having students track these emotions and the events around them also supports students’ reading comprehension.

SEL Journal Writing

Vignette: Teaching and supporting Daniel

Today is the worst day ever!” Maggie yelled as she stormed to her seat after Maria asked her to take a break from playing a partner game. Maria sighed. For Maggie, every day was the worst day ever. Maria mentioned this to the school counselor, who suggested Maggie start journaling about her day to reflect on both the good and challenging times of the day. That’s a great idea, Maria thought, for my students who like to write. In fact, I will try that with all my students. But Maggie and Daniel hate writing! How can I help them journal their feelings?

Journaling is an excellent way for students to individually show what these new concepts mean to them. This can become a daily or weekly routine done at the start of a student’s day or after a student finishes an assigned learning task (for example, instead of reading a book when a student completes an assigned task, they can journal).

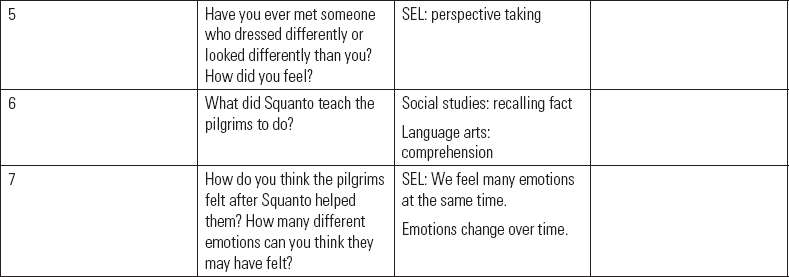

Also, consider allowing students to pair drawing with their writing, or encourage them to create a graphic novel that portrays their feelings and thoughts on the topic (see figure 4.21). Graphic novels break down thoughts into small boxes, encouraging students to think in a linear, cause-and-effect manner, which is essential for comprehending SEL. In using the graphic novel approach, you can place the main problem-solving situation in the center of a pre-created comic strip. Then, ask the students to draw and write what happened before and after that social situation (see figure 4.22). This supports the students’ SEL building blocks 4 (social-emotional regulation) and 5 (logical and responsible decision making).

SEL Projects

Vignette: Teaching and supporting Daniel

Man, Maria found herself thinking, it has been one long year! But I’m so proud of how I’ve noticed what my students need and can embed it into the day. The end of the year is going much smoother than the beginning, and I see real change in Daniel and overall SEL growth in all my students. Now that our team has done this work together, it should be easier to put into place next year. One team goal for next year is to increase our use of projects. I shared with my team how Daniel took so much ownership of the project I gave the class at the end of the year, and my teammates also noticed the same for many students in their classrooms. In fact, it was the most engaged we saw some of our students. As I reflected with my teammates, I wondered if I could have used project-based learning earlier in the year to not only engage Daniel, but also help him develop his emotional regulation. We all agreed this would have been good for all our students, not just Daniel, so we decided to plan for project-based learning earlier in the year and find ways to continuously incorporate it into our current curriculum.

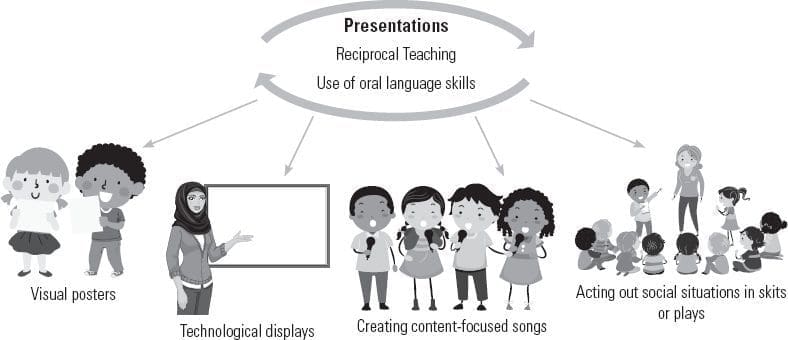

Authors recommend that projects and presentations are a great way to engage learners and integrate multiple curriculum areas, including SEL. It creates opportunities for students to practice SEL building blocks 2 (reciprocal engagement) and 5 (logical and responsible decision making). Using the reciprocal teaching structure, students learn through the process of creating and teaching concepts and ideas to their peers, and by being taught the concepts and skills through presentations and projects their peers create. Instead of the traditional model of the teacher instructing the students, the students are teaching each other, and the teacher is a facilitator. Students can teach their peers and present social-emotional learning in various formats. Students can create SEL presentations (see figure 4.27) using various digital presentation software and videos. Students could also present SEL skills and concepts by using visual poster presentations, acting out social situations in skits or plays, or creating their own SEL-focused songs.

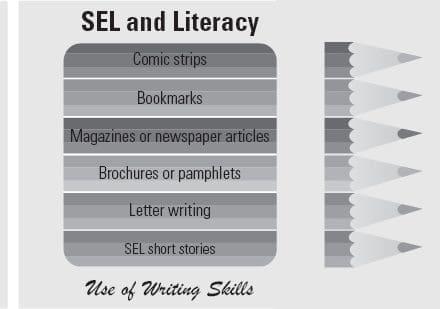

Students can also learn through various SEL projects that specifically support literacy and writing skills (see figure 4.28). Ideas may include creating comic strips, bookmarks, magazines or newspaper articles, and stories that teach specific SEL concepts or skills.

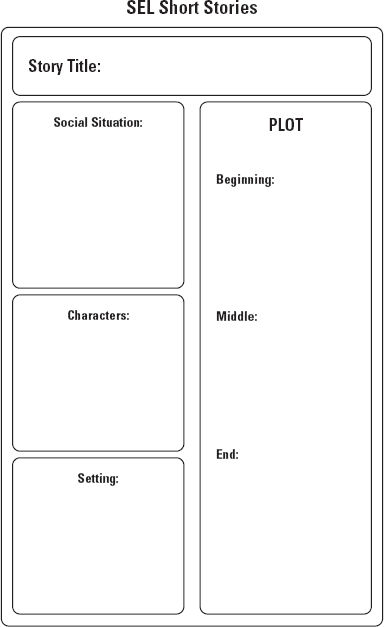

Some upper elementary teachers have their classes pair with younger primary classes, and have their students read to younger students (or the younger students read to the older students). Another option is to have upper-grade students gear their SEL projects toward younger students, instead of creating and presenting them to their grade-level peers. It might also be important to use scaffolds to help students create their SEL projects. Figure 4.29 (page 206) is a graphic organizer that students can use when creating social stories. Dexter and Hughes (2011) find that graphic organizers can help students (particularly students with learning disabilities) make abstract concepts more concrete and help transfer knowledge and ideas in new or unusual situations. Christopher Kaufman (2010) breaks down the executive functioning skills necessary during the writing process and states that teachers should require all students to use prewriting processes and organizers, not just those with learning disabilities.

Project-based learning (PBL) is another great way to integrate social-emotional learning. According to John W. Thomas (2000):

Project-based learning (PBL) is a model that organizes learning around projects. According to the definitions found in PBL handbooks for teachers, projects are complex tasks, based on challenging questions or problems, that involve students in design, problem-solving, decision-making, or investigative activities; allow students to work relatively autonomously over extended periods of time; and culminate in realistic products or presentations (Jones, Rasmussen, & Moffitt, 1997; Thomas, Mergendoller, & Michaelson, 1999). (p. 1)

Often project-based learning incorporates multiple academic content areas. Social-emotional learning typically occurs naturally through project-based learning, but can also be directly planned for and embedded into PBL. Projects can also be an avenue for building relationships with families, as families can be encouraged to contribute to the process. Students can also use technology to enhance their projects.

Conclusion

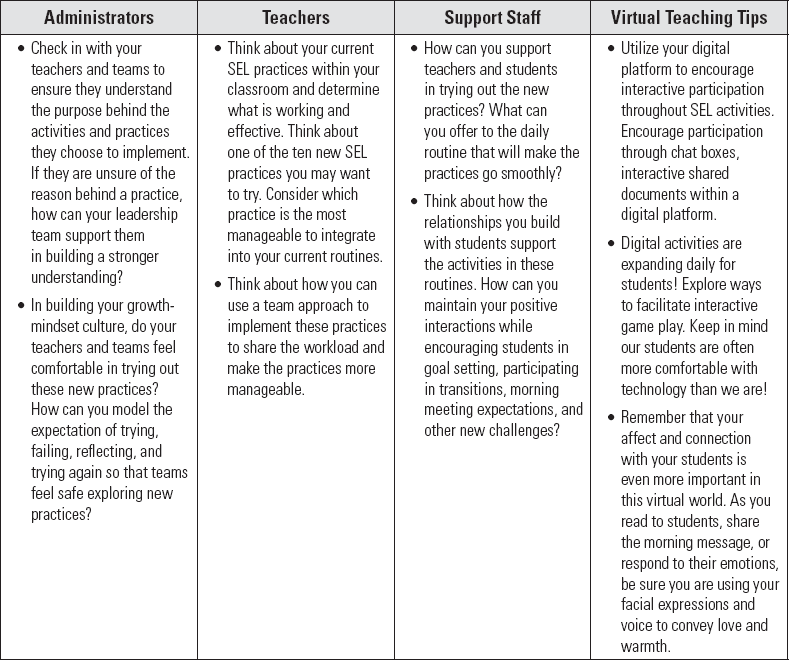

Authors provide Tips for Administrators, Teachers, and Support Staff:

Figure 4.35 has tips and reflection questions about the contents of this chapter. As you consider these questions and the next steps, reflect on your current practices in your own classroom and school.