I am sure many educators have heard this before:

Many students who disrupt learning are actually struggling academically, and would rather be seen as “the bad kid” than as “the stupid kid.”

Educators know how important engagement is for student learning, but how do you meet the goal of education “prepare the young to educate themselves throughout their lives”?

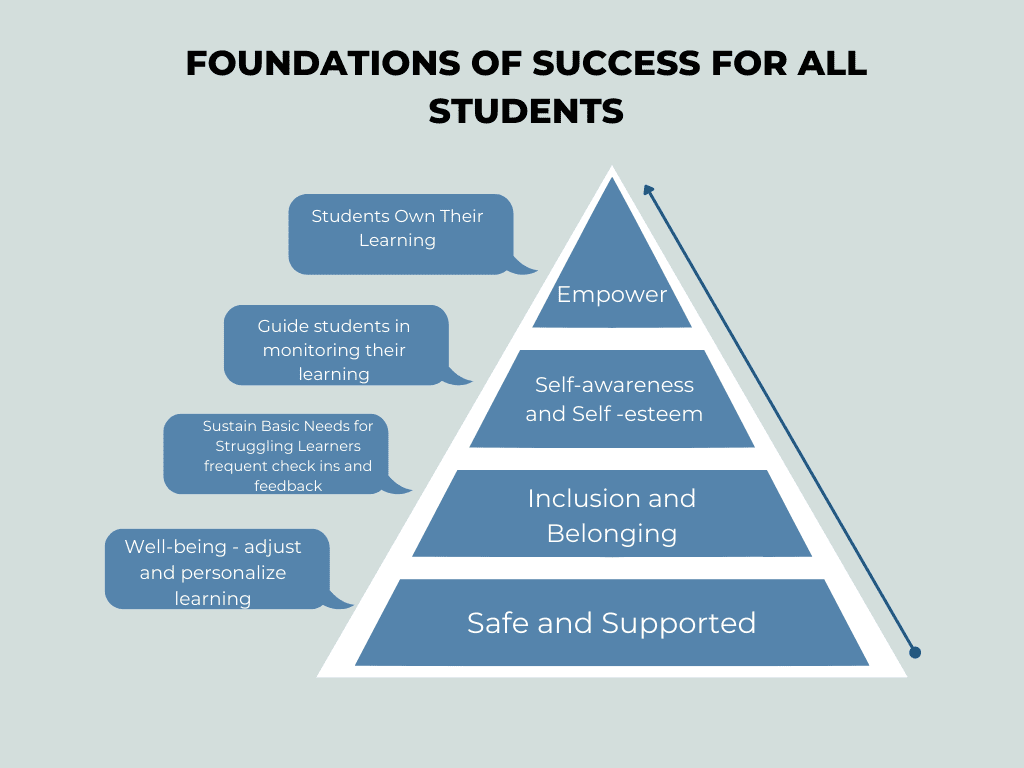

Authors Laura Greenstein and Mary Ann Burke of Student-Engaged Assessment Strategies to Empower All Learners made an analogy of groundwork for success for all students to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs:

Greenstein and Burke focus on beliefs, habits, and underpinnings that prepare students to be insightful self-assessors throughout their lives. Greenstein and Burke’s beliefs confirm what I read from the article “Empower Students Through Creativity and Choice” that social emotional learning can be as important to embed into all learning when applying academic and transferable skills.

Foundations of Success for All Students

Safe and Supported

Greenstein and Burke emphasize if children are to succeed, they must first feel safe and supported but for some learners, life is not safe. Authors present information about a student named Jake.

Jake qualified for free/reduced lunches, but his mother was too proud to accept help. Jake would routinely show up at the learning lab, hoping there were leftovers from the day’s snack. The teacher always put a little aside for him, and he was always appreciative in his own way.

By his junior year, he had taken and did well on the military aptitude test and enrolled in the Delayed Entry Program. Two years after his high school graduation, he returned to his school to tell his story and thank his teachers, counselors, and especially the principal who mentored him through the process. He was proud of his promotion to specialist and had earned a service ribbon. Privately, he told me he was glad to finally pay his mother back for all the sacrifices she made for him. For Jake, building the foundations of food, medical care, and stability in his life were essential foundations for success.

According to the authors, well-being in assessment comes when students clearly understand the learning intentions and have opportunities to personalize and adjust them in ways that make sense to them and support their success. For example, authors use deconstructing large-scale standards into actionable and measurable interim steps:

“Compare two decimals by reasoning about their size” (CCSS Math 4.NF.C.7) becomes “I can read and understand decimals and put them in order.” When a student named Carlita can’t remember what the < and > symbols mean, her teacher posts, > means is greater than, Carlita has an aha moment and completes the task accurately. Carlita’s teacher made her feel at ease instead of apprehensive.

Inclusion and Belonging

Inclusion and belonging are another step toward personal achievement once learners’ needs for safety and well-being are met and they feel academically and emotionally secure in their classroom. Greenstein and Burke believe standardized tests are required, but they may not sustain these basic needs for struggling learners. Authors want to include assessments that are inclusive of all learners, routinely incorporated within teaching and learning, relevant to the student, align with learning, and comprehensive in their use of a spectrum of methods and actions that support progress toward mastery. Instructionally supportive assessment is one of them.

Instructional supportive assessment relies on frequent check-ins for understanding, as well as feedback that clarifies misunderstandings and guidance on next steps, hence, informative assessment. Authors state that “these assessments give learners voice, such as adding annotations for their responses or asking lingering questions within the assessment”. Greenstein and Burke give prompts for feedback that can come from teachers, as well as peers: “What you said about _ is clear, but I am still confused on.” Or “I see you included _ but have you also thought about _?”

Self-awareness and Self-Esteem

Students develop clearer ideas about who they are and how they think as they mature. At this stage, students begin to recognize thier strengths and struggles. Authors note that this development of self-awareness and self-esteem can be fostered by assessments that encourage and guide students in tracking their learning. Greenstein and Burke point out that when students become reflective and flexible assessors, they also can personalize learning intentions. For example, when given a choice in showing understanding of event sequences, Wei makes an instructive video on writing a graphic novel, while Fiona wants to illustrate a user’s guide to sustainable gardens.

The Hanover research study on the “Impact of Student Choice and Personalize Learning” from “Empower Students Through Creativity and Choice” points out that choice in different parts of the learning process can affect motivation, participation, and achievement. And examples of students Greenstein and Burke point out that students’ motivation and participation increased once the apprehensiveness and pressure are gone.

Authors give another example that shows that consistency and clarity of learning goals are central to success. A student named Max said to his teacher, “I want to try something new for my project, but don’t want to be penalized for lack of creativity, since it’s the first time I am using Piktochart, an infographic maker.” Max and his teacher mutually agreed to count the content ratings of the rubric at 80 percent and the design ratings at 20 percent after a brief conversation.

Greenstein and Burke give many student owned elements of assessment shown to increase success. These include:

- clarity of purpose

- Relevance to the learner

- authentic experiences

- Personalized meaning

- Purposeful reflection

- Informative feedback

- Gauges of progress

- Reliance on coherent assessments and measurements

Greenstein and Burke suggest that a good place to start to include student owned elements of assessment in instruction is by translating big picture ideas into local actions. Authors have a good point in stating that “from the start, teachers, students, parents, and communities must have clarity of what learners are expected to know and do (standards). They cannot wait for test results after the learning cycle is over or the school year has ended to learn about students’ achievement.” To prevent this from being a problem, authors recommend being proactive at the local level – students and teachers – by translating big-picture outcomes into local goals and short-term learning steps. Proactive also means, authors explain, “taking responsibility for your decisions and actions.” Here is how to incorporate this idea:

- Introduce this idea by asking students about their experiences getting caught in a rainstorm or unintentionally breaking something: Have them think about what could have prevented it.

- Then talk about being proactive in school, by asking for help on a specific stumbling point, or helping classmates on the verge of tearing up their paper, or throwing their tablet across the room.

A Case in Point:

Greenstein and Burke present Garth, a student having difficulty sorting words into verbs or adjectives:

Rosie showed her list to him and explained that adjectives describe things. She showed her understanding by stating that furry describes a dog and beautiful describes a hat. Rosie then clarified that verbs are action words, such as speak, ran, feel. She stated, “I know it can be confusing when you have to decide if confuse or confused is a verb, but I don’t think that is on our list. Let me know if you need more help.” Authors point out that this simple act of helping another is an important part of engaging and empowering students as assessors.

Greenstein and Burke highlighted what Proactive Assessment is about:

- It is more timely, focused, and actionable than benchmark and summative measures.

- It relies on self-reflection in relation to learning intentions and self-reliance in responding to informative feedback.

- It engages students in explaining what they learned, comparing it to their goals, identifying lingering questions, and making recommendations for next steps.

Authors write ” a proactive mindset is ready to face the unexpected in relation to learning outcomes.” Anton is a good example. He explains that “the review sheet made me realize that I skipped the third stage. I reviewed what we learned and corrected my work. Now, I think my grade should change from 79 to 84.”

Know that “It is essential to keep the student at the center of assessment,” emphasizes the authors, because “if multiple types of assessments are used for instructional purposes, they must be made specific to the standards yet responsive to the students.” Another point I believe is crucial to understand is that according to Greenstein and Burke, “the motivational value of assessment is enhanced by in the moment feedback, whether from the teacher, peers, or a computer program. Relevant and engaging tasks combined with embedded formative assessment can incentivize students to move toward finding answers and solutions.”

Greenstein and Burke cite Andrae, Huff, and Brooke (2012) when they point out that being student focused means about students’ strengths, needs, and interests; promoting learning through growth; involving students in setting goals; tracking progress; and determining how to address any gaps (2).

Empower

So, this happens when students own their learning:

Conclusion

Greenstein and Burke encourage you to think about how Matthew Lynch (2018) summarizes the value of students’ owning their learning in the above infographic. Do you agree or disagree with? Are there ideas you would add or delete?