Shape Project Design with Clarity

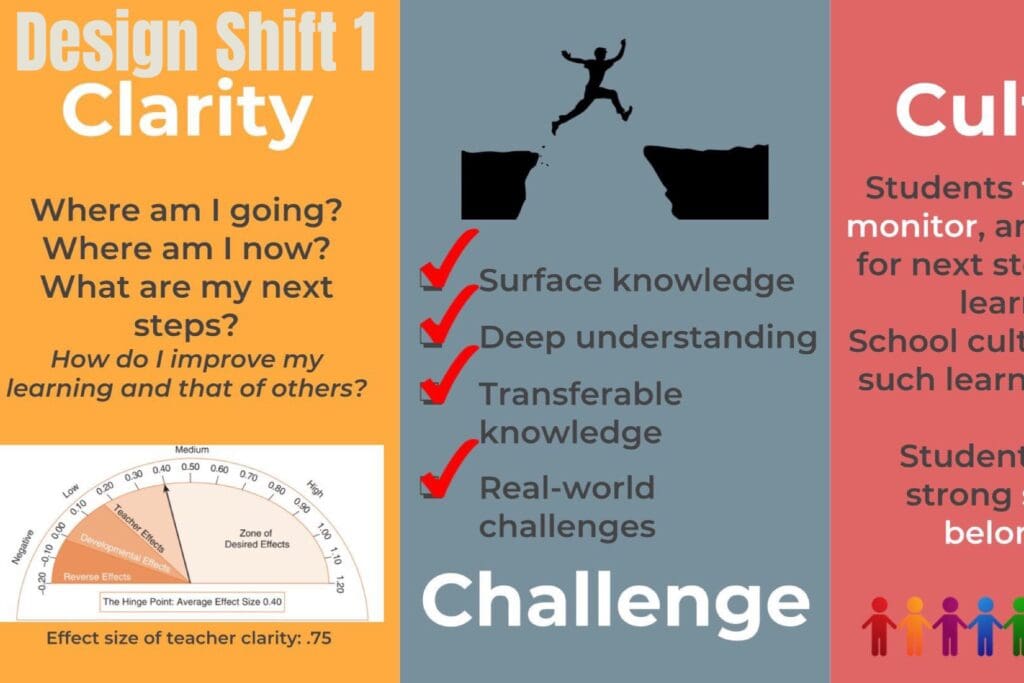

Michael McDowell’s first design shift, Clarity, focuses on shaping project design (PBL) to enable students to address question 1, where am I going in my learning? McDowell ensures clarity by using two design challenges that emerge for teachers:

- Supporting context and tasks from learning intention and success criteria

- Scaffolding surface-, deep-, and transfer-level expectations effectively

Where am I going?

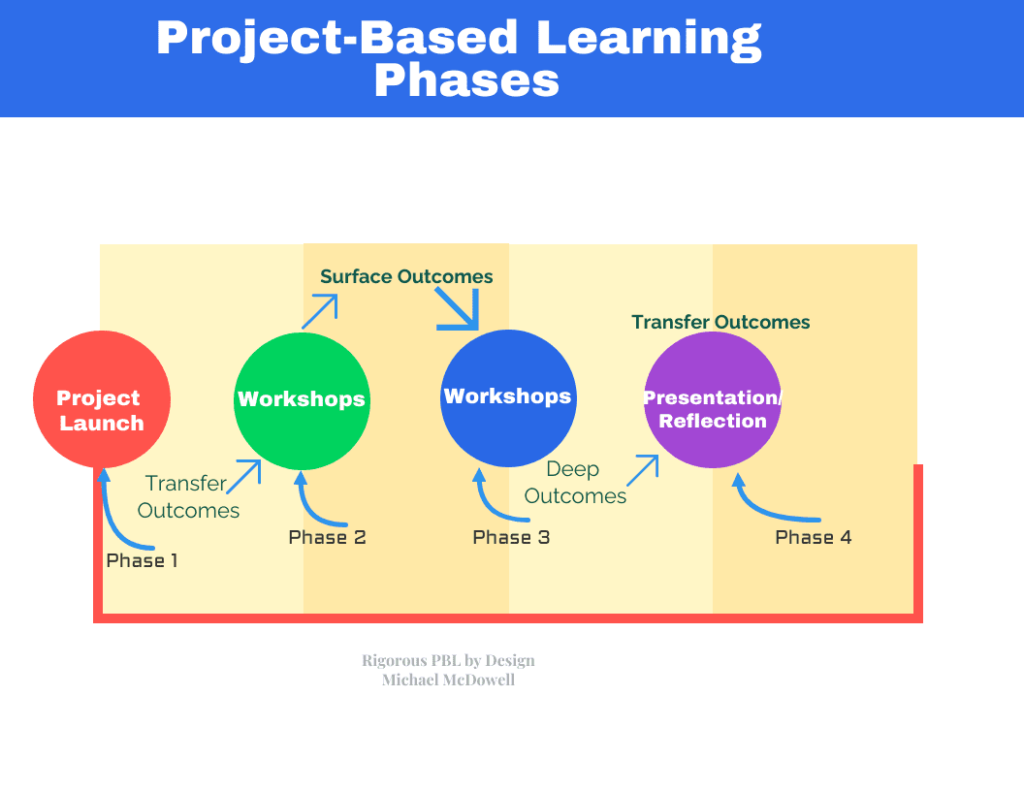

One of the distinguishing attributes of problem-based learning (PBL), when designed correctly, is that clear learning intentions and success criteria are provided at the beginning of the learning sequence (see Figure 3.1). McDowell emphasizes that teachers introduce students to the surface, deep, and transfer expectations they will need to discuss during the project in phase 1 project launch. McDowell believes that by overtly articulating expectations early on, students have a clear picture of where they are going over the next several weeks. As students engage in Phase 2 and Phase 3 work, they have a clear reason for why they learn surface- and deep-level knowledge, as it is connected to the project’s transfer learning expectations. Also, an indirect result of this process is that showcasing high expectations for student learning upfront sends an implicit message to children that teachers believe they can learn and learn at high levels.

First Design Challenge: Be Clear About Separating Context and Task From Learning Intentions and Success Criteria

McDowell gives an example of separating context and task from learning intentions and success criteria:

Project Snapshot: The House M.D. Project

In the following project, students are provided with details on an ailing patient at a nearby hospital. The health professionals at the hospital are interested in learning about the students’ ability to discern the diagnosis, craft a treatment plan, and identify a prognosis. The health profession will go to a special presentation in a few short weeks to understand how students apply cell biology, microbiology, and immunology to address the needs of the patient.

Key questions:

As you read the initial description of the project, think about these questions:

- What are the key learning intentions of the project?

- What are the success criteria of the project at surface, deep, and transfer levels?

The House M.D. project is inherently context rich, and teachers must support students in separating the project situation or context from the learning intentions and success criteria. Students may focus their mental effort on diagnosis, prognosis, and identifying a treatment plan for a patient at the hospital. McDowell believes it makes sense, as the project’s product expectations are laid out in the example. However, as a teacher, I’m looking for students to understand and explain the relationship between bacteria, viruses, and protists to the immune system.

The House M.D. Project is the vehicle or context to introduce the immune system to my classroom. If students do not understand the learning intentions and success criteria in the project, they often cannot transfer their understanding to new contexts and situations, and they will lack the surface- and deep-level understanding I want them to gain. By consciously separating learning outcomes and success criteria from the project context, students can readily transfer their learning to various situations and articulate their understanding in various ways.

McDowell cites Dylan William’s (2011) example of a learning outcome, context, and confused learning goal below:

| Learning Outcome | Present an argument either for or against an emotionally charged proposition. |

| Context | Assisted Suicide |

| Confused Learning Objective | Present an argument either for or against assisted suicide. |

McDowell notes that learning intentions and success criteria can get muddled and blend contexts, confusing students and teachers in clarifying goals and expectations. Clarity may also be affected by including tasks within learning intentions and success criteria.

Second Design Challenge: Scaffold Surface-, Deep-, and Transfer-Level Expectations Effectively

Carefully scaffolding the complexity for students to meet the transfer-level demands of project questions and tasks is what the second design challenge is about. McDowell believes students must be introduced to learning intentions and success criteria in a PBL classroom at surface-, deep-, and transfer-level expectations. McDowell specifically mentions and emphasizes building success criteria at specific levels of learning in the following way: surface learning (single and multiple ideas and skills), deep learning (combining or linking ideas and skills), and transfer learning (extending ideas and skills). Figure 3.5 illustrates these levels of learning.

Surface-, Deep-, and Transfer-Level Learning Rhetoric Figure 3.5

| Build Knowledge | Make Meaning | |

| Single (One concept, idea, skill) | Multiple (More than one concept, idea, skill) | Link (Connect concepts, ideas, skills) |

| Name, tell, restate, define, identify, recall, recite, recognize, label, locate, match, measure etc. | List several elements, describe and explain using context, classify, give examples and non-examples, perform a procedure, summarize, estimate, using models to perform the procedure, construct a simple model etc. | Cite supporting evidence, organize, outline, interpret, revise for meaning, explain connections or procedures, contrast, compare, synthesize, verify, show cause and effect, critique etc. |

Voices From the Trenches

Teresa Rensch

Director of Curriculum and Instruction

Konocti Unified School District, Lower Lake, CA

Konocti Education Center (a 4th–12th grade school) has had two years of full implementation as a health magnet, visual arts, and PBL school. Konocti Education Center landed on PBL to bring an alternative instructional method in hopes of raising the level of relevance of school for a particular set of students in fostering 21st century capable learners. Whether a school or district, when attempting full-scale implementation, I recommend partnering with Corwin to build a viable strategic plan. Corwin can support an effective professional development plan that allows staff to gain new, research-informed knowledge, have time to make meaning of the new learning and construct the new learning for the classroom, receive ongoing coaching support, and ultimately build capacity within one’s own system.

The partnership includes large-scale needs assessment and guidance in interpreting the data to narrow the focus and initial action steps that will affect student learning.

As director, I spent my first year in the school gaining knowledge through observing classes. In year two, we now make an effort to include students in reflection around their academic progress at incremental junctures in the PBL unit. There has been a shift to include more frequent formal and informal formative assessments. This supports teacher clarity around the students’ levels of learning along the way. It also supports the students’ awareness of their own learning progression. One thing that stands out about this school is the collaborative spirit involved in creating the school-wide PBL units. I particularly appreciate the reflective piece at the end of the school wide PBL unit, in which the school professional learning community (PLC) evaluates the success of the unit.

If I were leading a new school initiative to implement PBL, I would include malleable steps with clear benchmarks at each phase of the implementation plan. I would incorporate the reflection component and data analysis as part of the implementation plan. I would ensure that key instructional strategies, like teacher clarity, were interwoven into the PBL units. Moving forward, we will continue to include John Hattie’s research into the methodology of PBL. The school collaborative teams will include regular intervals of data analysis and progress monitoring around the effectiveness in the delivery of PBL units and lessons.

In this book, Michael McDowell provides a practical application manual for effective implementation of PBL. When I say “effective,” I mean the hinge point of visible learning. McDowell delivers substantial research supporting each shift in PBL design. This book is premised on the realization that students start each PBL unit in the learning pit, and then the journey begins through the intentional arrangement of instruction, intervention, and feedback. Through the implementation of these three shifts, students cross the finish line at the end, each PBL unit out of the pit, at a stage of illumination and discovery, at a stage of deep and sustainable learning.

So, PBL has shown substantial yields when students are prepared for transfer-level work, but if student achievement at the surface level, PBL has a relatively low effect.

Conclusion

I agree with McDowell (2017) that “instructional design is about creating a plan that substantially moves a student’s understanding and skill set to much higher levels through a project (or unit or lesson). To accomplish such a feat, expectations for learning must be clear, performance levels well established, and next steps that students need to take in their own learning process must be well planned.” (pg 41)

Next Blog: How to Design Project-Based Learning with Clarity in 5 Steps

Reference

McDowell, M. (2017). Rigorous PBL by Design. SAGE Publications, Inc. (US). https://bookshelf.vitalsource.com/books/9781506359014