Using Student Choice to Support Motivation

Chase Nordengren, author of Step into Student Goal Setting book, writes ‘no matter how your classroom is designed or how much authority you exercise over students, they always retain the most important decision: the choice to engage in learning.’ It got my attention.

Many educators face this dilemma of how to engage students in learning. My question is how do you engage students in learning using student choice? The answer can be found in the Giving Student Choice and Strategic Moments in Learning Cycle webinar, where presenters DR. Caitlin R Tucker and Kareem Farra, Founder of Modern Classroom, pose important questions to facilitate conversation about using student choice to support motivation.

The presenters pose the following questions:

What comes to mind when you hear the phrase ‘Student Agency’?

Author and presenter, DR. Caitlin R Tucker, starts the webinar by using the word cloud slide to ask educators to throw any words that come to mind. The word that rises to the top of the word cloud is Choice, followed by independence, engagement, voice, autonomy, confidence, and freedom.

Why is student agency so valuable?

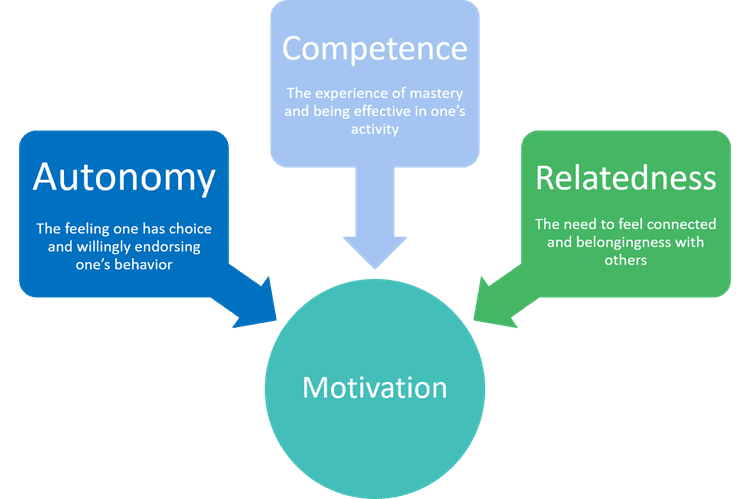

Student agency ties into what we know about human motivation. DR. Tucker describes motivation needs three things:

Student who can have independence and make key decisions, he or she has autonomy.

Students with confidence in their ability to accomplish tasks, navigate and execute on different tasks, then it is easier to do when they have a choice of how to go about it. This is called competence.

Students who complete a particular task will feel connected to the community for things like support. This is called relatedness.

DR. Tucker points out that teachers acknowledge that giving student choice can be scary, but something like student agency can give students meaningful choices in their learning experience. DR. Tucker knows it’s scary to give students meaningful choice, and teachers sometimes don’t know where to start. But DR. Tucker wants to make it clear that as we think about why student agency is so valuable, it is the part of this puzzle around motivation. DR. Tucker continues to explain, ‘We hear a lot about teachers who are a little frustrated, they don’t feel like students are necessarily super motivated. Teachers wish students are more engaged in learning. Maybe this is one simple way to think about student engagement to support motivation.

In the webinar, one question presenters asked is how students feel about no capacity to make decisions about what they do. This leads me to think about How Students Experience and Talk About Agency, a chapter from the book Student Agency: Honoring Student Voice in the Curriculum. In the book, author Margaret Vaughn asks students about agency:

What must students say about agency?

Vaughn points out that students emphasized the power of having a voice and having a choice in their roles as learners. Students who had agency felt they were positioned as knowledgeable decision makers and individuals capable of exerting influence in their learning contexts.

These responses are from students when asked what agency means to them:

VOICE AND CHOICE

Agency Means…

“Agency means having a choice and letting my ideas be heard to do what I’m interested in.”—5th-grader, female

“To me, as a student, agency means that I get to have a say in my education. It allows me to voice my opinion on what I want to learn, and how I want to learn it. Everyone has their own way of doing things, no matter what it is, me included. By giving students a choice, it allows them to discover and use the way they learn the best way they can.”—7th-grader, female.

“Having a voice in school.”—10th-grader, male

“Agency as a student to me feels like free speech and a say at what happens in school.”—8th-grader, male

“Having a voice as a student would certainly make me feel more involved in school and more valued.”—9th-grader, male

“Having agency as a student means quite a lot. You can have a part and voice in your own education, with guidance. It’s important to take part in your learning, not wait for others to do it for you.”—6th-grader, female

“Being able to decide things as a whole school by possibly voting or being able to choose your classes.”—6th-grader, male

“It means being able to choose what my day will look like and what type of activities I would prefer to do in school. It would be being able to choose what kind of learning I want to do, whether that’s online, reading from books, lectures, hands-on, or more.”—7th-grader, female

“It means being able to freely say your opinions to others to help improve something. In this case maybe the school system or rules made in school.”—3rd-grader, male

“As a student, having agency would make me feel that grade school will help me learn more about what I want to become after high school, even if the classes only cover the basics. I still feel that schools should require students to take classes from a variety of subjects, especially in earlier grades, to help students branch out and see what they enjoy.”—8th-grader, male

Vaughn beliefs by inviting students’ voices about their experiences and wonderings, schools can begin to rethink how to structure activities conducive to student agency. Vaughn cited “schools can engage in participatory action research, a process by which students become integral researchers, observers, and change agents through collective decision-making”. “Participatory action research supports an approach to fostering collective agency in students by inviting students and communities to understand and take action toward community change (Cook- Sather, 2020).”

Vaughn asks another question:

Do Students Feel They Have Opportunities to Make Choices and Share Their Voice?

Vaughn asks students to share opportunities in schools and in their classrooms, where they made choices and shared their voice. Interestingly, students shared minimal opportunities where they made choices and shared their voice. Responses ranged from none to describing activities outside of school.

Here are responses:

“I don’t feel like I have a lot of choice. She usually has a plan for the day, and it doesn’t change—we can’t change it.”—4th-grader, female

“I have almost none—no choice at all.”—7th-grader, female

“I feel I do not have much choice as a student, because I am almost never given an option but a command.”—8th-grader, male

“In some of my clubs, such as National Honor Society and Beta Club, but other than that, I feel as if I have had no voice in my school.”—11th-grade, female

“I feel like I have no freedom to choose.”—11th-grade, female

If students feel they have no capacity to control how they learn, then it begs to ask the next question posed by presenters of the webinar:

Should We Give Students a Decision in Choice? And When Should We Not? How does this process work?

Kareem Farra believes these questions are critical for a couple reasons:

One, educators sometimes think it only happens through the lens of content, that it’s like they get to choose what type. Farra then asked DR. Tucker, “What do you think about this?”

DR. Tucker says “When I work with teachers, I talked about three moments in a learning cycle where we might want to consider giving students agency. It doesn’t mean they will make every choice every time, but it’s these moments where we are at least asking ourselves as the architect of this learning experience, where would make sense for learners to make a meaningful choice?” She continues to say “Where might that choice make learning more interesting, more relevant, or remove a potential barrier in that student’s pathway?” “And so, of course, the first is around content on what to cover.”

DR. Tucker explains teachers are tasked with covering ridiculous amounts of content and curriculum, and usually we have to cover these huge topics and issues, so where are those moments? DR. Tucker believes we might let a student select the lens they look through or a smaller part of a larger topic interesting for them personally. DR. Tucker gives two examples:

“I was coaching in a second-grade classroom. Students were going to do a science unit, it was getting them familiar with animals and animal habitats, and how animals impact their habitat, and vice versa.” DR. Tucker says. “And the first thing the teacher did was ask students, okay, I want you to choose an animal you are interested in. You will be approaching this unit through the lens of this particular animal that you chose, instead of trying to like study a bunch of animals. It was so fascinating, because that one little choice kids were so pumped, and they chose just this huge array of animals to be their lens for this unit, which I thought was fascinating.”

DR. Tucker also shared her experience as a secondary English teacher. DR. Tucker describes “even in my own experience, part of my standard is always doing informal research”. DR. Tucker says, “So, we will read a text that I want students to know about the historical background.” DR. Tucker continues to explain, “if we are going to read Romeo and Juliet, let’s explore Elizabethan England, but instead of what I did in the beginning of my career, which was they were all going to research this ridiculous huge topic.” “I remember, like five, six years in, I thought, kids hate this.” DR. Tucker laughed.

When DR. Tucker reflects on her experience, she did not get that much out of the students. DR. Tucker thought, “What if I just give them a laundry list of lenses, like do you want to research fashion in Elizabethan England, or the monarchy, diet or entertainment Crime and Punishment, the plague and other illnesses?” Just that option of choosing which lens students look through, students are much more willing to learn about this period.

DR. Tucker explains the second round of how or the process the students learn about the content. DR. Tucker says “this is where that link in the motivation comes into play”. DR. Tucker continues to say “Conversation about competence becomes so important, because we know that not all students will be successful with the same pathway”. “We can actually provide different process pathways that they can choose from, so they can navigate a task with more confidence. This might be as simple as do you want to decide what steps you move through to get from point A to point B?” This can make a big difference in terms of how confident they feel. DR. Tucker says “if we have everybody read the same text, because it is what it is required on Tuesday, but we want them to actively engage with that text”. Maybe they do not all have to take traditional Cornell notes, maybe they can decide. Do I do Cornell notes or do I do a 3-2-1 reflection at the end, pulling out information?” DR. Tucker explains, “just giving them simple options for how you want to engage with this text?” “What would make this meaningful for you and to create products that demonstrate their learning?”

DR. Tucker encourages teachers to think about that content process, product, lens when we give students agency. So the key to student choice is to make a huge difference when you just layer in a little bit at a time.

If I give Student Choice, I will not get through my Scope and Sequence.

Farra asks DR. Tucker, “How do you respond to folks who say choice will make the experience less rigorous or difficult to hit all the content standards that need to be taught?”

DR. Tucker makes this point, “Some of us don’t trust students to make good choices, and I get it.” DR. Tucker says, “They won’t always make the best choice, but if they don’t ever get a chance to experiment, did it work for me or did it not work for me?” DR. Tucker continues to point out that “I think we are cheating students when we don’t allow them to start developing these critical self-regulation skills, social emotional skills or develop self-directed learner skills”. “They will not always make great choices, and that’s an opportunity to talk with them and say okay, why did you make this choice? Why don’t you think it worked? How might we make a different choice in the future?” DR. Tucker says “but it doesn’t mean I will give you a choice, because I don’t know what you will choose, and I don’t think you will choose something challenging”. So the point is, as DR. Tucker points out, “Place opportunities where students have autonomy and agency, and it actually increases engagement and therefore increases students’ love capacity to master content.”

The conversation between Farra and DR. Tucker turns to effective decision-making. Farra points out that “we are trying to empower students to actually be good at decision-making, because we as adults have to make decisions all the time”. So, Farra said, “then the big question is how do you support effective decision-making in a classroom?” How do you actually coach a teacher to coach students on decision-making?” Here is Farra’s response:

“What I learn over time is actually let the students find their pathway to success, and then communicate with them afterwards when they haven’t achieved success on choosing the wrong path. We see this all the time in our classrooms, where you give students student-centered learning choice: Would you rather choose an option? Or would you rather do this or that? Would you rather option into every lesson? This can start to get you and your students comfortable making choices. Something that we don’t talk about as much is that many students have spent years in classrooms where they don’t get to make hardly any decisions. So you put a decision in front of them, and there are some students who freeze and don’t know what to do, because nobody has ever asked me this before. One option is modeling.”

DR. Tucker suggests giving students the space to begin a task for multi-step assignments. And then at the end, think about what strategies might I use or did I use, how effective were they, and what resources do I get at my disposal? Or what resources did I lean on?

DR. Tucker and Farra pose these questions to help educators understand how student choice can support motivation.

If you would like to watch the webinar, you can create an account under edweb.net or if you already have an account, you can register for this webinar in both cases. You can earn 1 hour CE Certificate.

My take away

After watching the webinar, I researched further into the three components of motivation. It is called

Self- Determination Theory. According to the article “Our Approach Self- Determination Theory” suggests “When rewards mainly motivate people, punishments, and internal pressure, they have a harder time initiating and maintaining their behaviors over the long term”. However, when people are more autonomous—that is, when they are motivated more by their value for the behavior, or by their interest and enjoyment of the behavior—they tend to be more persistent in their behavior, feel more satisfied, and have higher well-being overall.”

In another article, “What is Self-Determination Theory?” suggests “people are actively directed toward growth”. Gaining mastery over challenges and taking in new experiences is essential for developing a cohesive sense of self.” Second, “While people are often motivated to act by external rewards, such as money, prizes, and acclaim (known as extrinsic motivation), self-determination theory focuses primarily on internal sources of motivation, such as a need to gain knowledge or independence (intrinsic motivation).

I learned extrinsic motivation is quick self-gratification that does not last long. I lean toward intrinsic motivation because it is more self-motivated, not by external factors and conditions. This is what students need, such as knowledge or independence (autonomy).