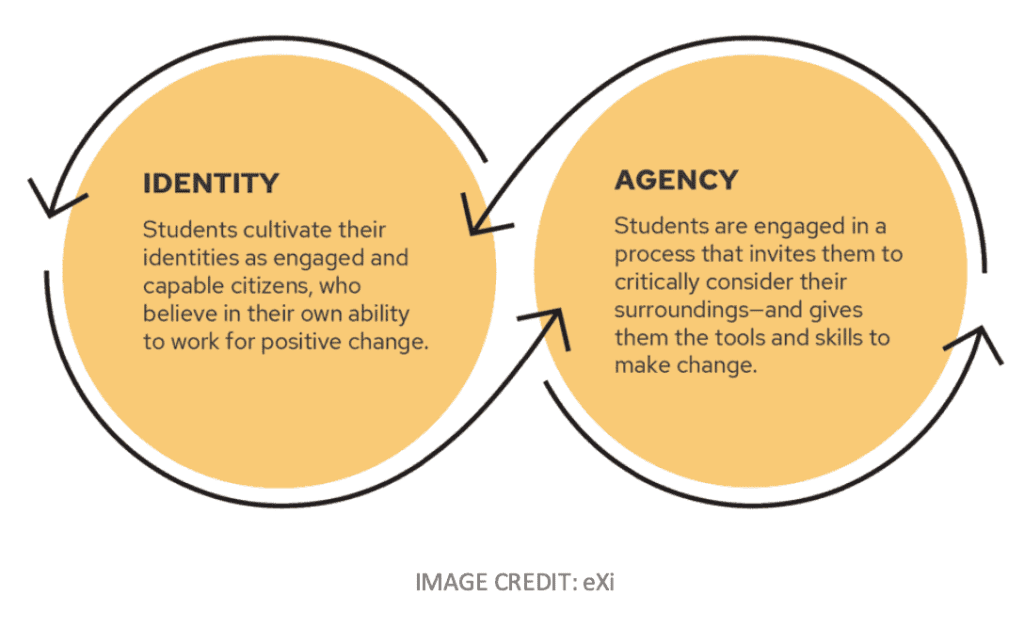

Identity and Agency Defined

Identity refers to our comprehensive understanding of our own features, our self- perception in relation to others, our perceived abilities, and our recognition of our weaknesses, as stated by Nancy Frey, Douglas Fisher, and Dominique Smith, the authors of the book “All Learning is Social and Emotional”.

Authors define Agency as the capacity to engage in self-directed and autonomous actions. Our self-assurance and ability to bounce back from challenges are shaped by our convictions on our ability to proactively respond. Identity and agency are influenced by both unchangeable and flexible frameworks, encompassing elements such as gender, race, sexual orientation, personal experiences, cultural heritage, and social status.

Teachers’ words and actions shape students’ identity, and agency (whether intentional or not). Authors suggest educators pay mindful attention to the development of our students’ identity and agency, because it is foundational to their learning and achievement. A child lacking confidence is unlikely to engage in academic ventures. Students lacking agency struggle to comprehend that they can change the course of their learning. Giving resources towards fostering the individuality and empowerment of each student yields positive outcomes in both academic performance and personal achievements.

Agency is intrinsically linked to identity, as it defines an individual’s ability to sue and mold their own fate. A sense of agency, like identity, is formed through social construction. The social capital of a young individual, which consists of their family, friends, school, and community networks, affects their feeling of agency.

“A person’s personal identity and sense of agency are the foundation of his or her emotional life. As human beings, how we see ourselves and our belief in our capacity to act upon our immediate world affect every waking moment of our lives.”

Student’s Identity and Agency Shape by Teacher’s Words and Actions

Authors show two instances where two students are affected by their teachers’ words and actions:

A first grader whose reading proficiency level was displayed on the screen by her teacher unintentionally revealed first grader student proficiency level at B. The other students in the class started whispering “Is she really on B?” and “That is low. I am at M. So B is really bad.” The first grade students refused to practice reading for weeks. The teacher’s action had triggered a new identity – “I am a bad reader, and everyone knows it.” It damaged the child’s relationships with other students.

A 9th grade student, Drew, was not yet as academically skilled as his classmates, and often compared himself to others in a negative way. Drew did not consider himself smart or capable. He gives up easily when faced with a challenge in the classroom. Some teachers view this as “lazy” and “unmotivated”. Drew’s 8th grade teacher wrote it on his report card. Drew enrolled in a new school where social and emotional learning is integrated in the classroom, which has a positive impact on Drew.

Ms. Avila, Drew’s new English teacher, takes this charge seriously. Ms. Avila distributed the writing prompt which focused on the first few chapters of George Orwell`s Animal Farm to the class.

When Drew read the prompt, he put his head down on the table and told Ms. Avila, who noticed Drew and checked on him, it is just too hard. Drew explained, “I’m reading the book, and it is OK, but I don’t know what the contradictions are, or even what that word means. I don’t know what Orwell is trying to say, and I don’t want to do this. I will just fail. That is what I do.”

Knowing that challenging tasks can trigger students with identity and agency struggles, Ms. Avila responded by asking Drew a few questions about the text:

- What are ways in which the animals changed between Chapters 1 and 6?

- How did Napoleon become more powerful?

- Why did Napoleon tell the other animals that Snowball was responsible for the ruin of the windmill?

- Why does Napoleon have dogs guard him?

Drew answered all the questions and enjoyed talking with Ms. Alvita. His teacher pointed out, “What I’m hearing is that you know a lot about this book. And those are some interesting ideas about how dictators develop. As you say, it happened slowly, and more animals had to go to Napoleon for answers.” Ms. Alvita suggested to Drew he use this knowledge and apply it to the writing prompt. “Would it help if we took the prompt apart and figured out the task together?” she asked. Authors pointed out at that moment, “Ms. Avila pivoted from supporting Drew academically to supporting him academically and emotionally.”

Drew wanted to know the meaning of the word contradiction and confessed, “I think I got stuck when I read that word, and not knowing it made me feel like I was going to fail.”

A detail as small as the meaning of a single word in a prompt can stop a student with a limited sense of agency in his tracks. By talking and listening close to students like Drew to spot when their agency is threatened, it can help show them ways they can get themselves restarted.

Recognizing Strengths Through Feedback

What do we mean when we advise you to help your students recognize their strengths?

Authors notice that students can so readily point out their failings more than their strengths, which is not surprising. We usually focus on weaknesses, gaps in learning, and deficits as teachers and parents. Because we want students to understand that failure is an opportunity to learn, we usually highlight errors that can guide them toward new learning, but we need to support positive identity development and agency. To do this, we should highlight students’ strengths and all the evidence of mastery they show us.

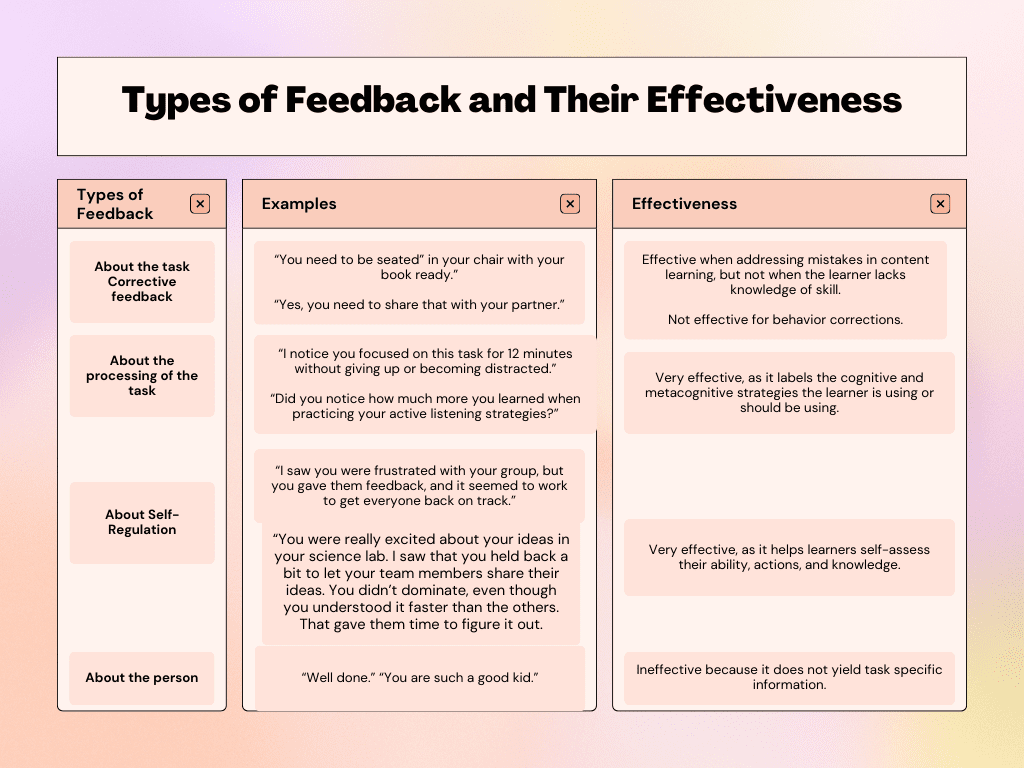

Authors suggest that feedback is one way to do this. There are four types of feedback authors point out that teachers and parents might employ:

- Corrective feedback: It is feedback about the task itself (the accuracy of the response). It is not effective in helping students identify strengths.

- Feedback about the processing of the task: It focuses on how the student approached the task. This feedback is a great choice in helping students recognize strengths, such as effort, strategy choice, focus, perseverance, and progress. It is also an effective way to approach identity related struggles, often voiced as “I’m just not good at this.”

- Feedback about self regulation: It focuses on students’ ability to manage their emotions and behavior during a specific situation. It is another good choice for helping students recognize strengths. Used to acknowledge their actions, choices, and responses, it can boost their sense of agency.

- Feedback about the person: It focuses on praise about the individual character traits. It is not effective, especially when it is vague praise like “You always do a great job.” or “You are smart.” Although we don’t want to discourage praise, it shouldn’t be confused with feedback. Unlike feedback, praise does not give a student any direction as to what to do next, or any information about why something he or she did succeeded.

Authors note that all four feedback can and should be used for academics. Authors want to highlight how to deploy them in the right circumstances. This is a way to integrate social and emotional skill development into your existing instruction. See Chart Below:

Authors also point out that there are other ways to show students strengths. One that stood out to me is Michael Perez, who helped his students identify their strengths. For each major assignment in his 6th grade class, he creates a checklist of strengths (from his master list of 20 items) that students can practice or show as part of their learning. For example, their lesson on ancient China’s contributions to the world included the following self-assessment statements:

- I can help peers without telling them the answers.

- I can summarize readings effectively.

- I can keep track of time so that my group finishes tasks.

- I can illustrate ideas and concepts in powerful ways.

- I can follow directions and explain directions to others.

- I can make sure everyone has the chance to speak in our group.

Authors notice how these statements are crafted to contribute to students’ sense of identity, and specifically foster agency. Authors point out that Mr. Perez also asks his students to identify one area of strength they would like to develop, and he works individually with them to develop a plan for this growth. Authors praise Mr. Perez for his use of these success criteria, which not only gives students academic targets, but also empowers students to pursue and reach them.

Self-Confidence

Self-confidence is shown in outward behaviors. Authors used the confidence and behavior table, which compares confident behavior with behavior associated with low self-confidence. This is from the article below:

| Confident behavior | Behavior associated with Lower-Self- Confidence |

| Doing what you believe is right, even if others tease or criticize you for it. | Acting in certain ways, because you worry about what other people think |

| Being willing to take reasonable risks and put forth effort to achieve better things. | Staying in your comfort zone, fearing failure, and avoiding risks. |

| Admitting your mistakes and learning from them. | Working hard to cover up mistakes and hoping you can fix the problem before anyone notices. |

| Waiting for others to congratulate you on your accomplishments | Talking about your successes as often as possible, and with many people. |

| Accepting compliments graciously (Thanks, I worked hard on that essay” “I am pleased you recognize my efforts”.) | Dismissing compliments off handily (“oh, that essay was nothing, really; anyone could have done it.”) |

Authors ask where self-confidence comes from? Authors cite Maclellan (2014), who reviewed the research literature on teachers’ actions to develop self-confidence in learners, recommends teachers do:

- Encourage student engagement through socially designed learning activities that promote self-concept and help develop knowledge.

- Plan activities in which students must explain their reasoning and debate the evidence on which they make their claims.

- Embed self-regulative and metacognitive activities in all lessons.

- Engage in dialogic feedback with students.

Authors mention teacher Elan Ramos, who has a quote from Eleanor Roosevelt framed on his classroom wall: “No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” Mr. Ramos often refers to the quote before students engage in complex tasks or provide feedback. Authors observed Ramos’ classroom discussion, in which he invites students to talk about ways they might stay focused and calm while making a presentation. “Public speaking requires skills that we don’t use every day,” he told them. “Let’s create a list of things we can do to keep calm and maintain our confidence. Authors view this as direct and deliberate work to address the issue of self-confidence as a contributor to students’ success. Students in Ramos’s group identified strategies they could use when they felt their confidence was compromised. Authors emphasize that it is necessary to track students’ confidence levels, as part of any effort to integrate SEL into everyday instruction. Authors remind us to be mindful of the language you use (so you don’t unintentionally undermine anyone’s confidence). Like Mr. Ramos, who gives students strategies

Self-Efficacy

Authors define self-efficacy as a measure of the belief in one’s ability to act (agency), complete a task, and achieve goals. Authors believe it influences self-confidence, and influenced by one’s skills sets.

Authors ask how teachers can influence students’ self-belief to enhance learning and goal attainment? Authors ask us to consider that the important factor in self-efficacy is believing the task is within your capacity, and a step toward that belief is seeing someone else complete the task successfully – particularly you.

Ways to influence students’ Self-Efficacy:

- Compiling short video clips of students performing various tasks and highlighting the keys to success. 3rd grade teacher sharing written or recorded reflections from last year’s class on mastering multiplication.

- Use literature by choosing books that carry a message about belief in oneself.

- A teacher’s mindful use of language, such as “It’s the power of yet,” when students can’t do something, “You can’t do it yet.”

Growth Mindset

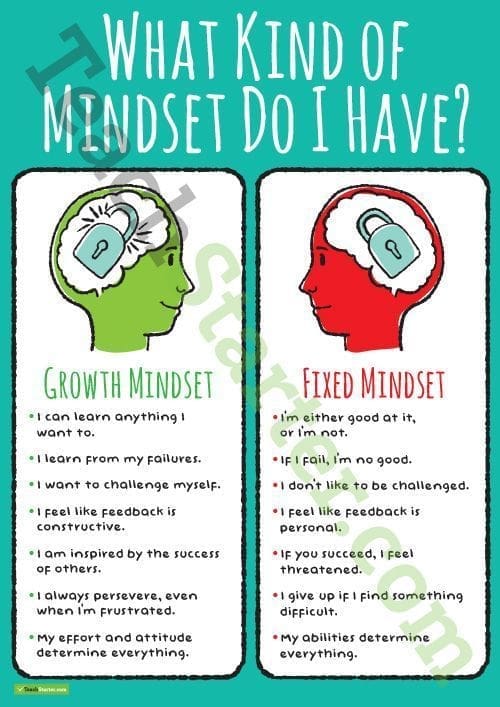

Authors believe mindset is the attitude someone holds about a task. For example, mindset about exercise: a necessary evil, an integral part of our lives, avoid it at all costs.

Authors explain that mindset expresses identity, agency, and self-efficacy as it applies to learning. Authors use MINDSET The New Psychology of Success by CAROL S. DWECK, PH.D. Fixed Versus Growth Mindset:

What a fixed mindset — intelligence is static. It leads to a desire to look smart, and a tendency to — avoid challenges, give up easily, see effort as fruitless or worse, ignore useful negative feedback, feel threatened by the success of others.

They may plateau early and achieve less than their full potential. All this confirms a deterministic view of the world.

With a Growth Mindset —

Intelligence can be developed.

It leads to a desire to learn and to —

a tendency to embrace challenges, persist in the face of setbacks, see effort as the path to mastery, learn from criticism, find lessons and inspiration in the success of others.

They reach ever-higher levels of achievement. All this gives them a greater sense of free will.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Carol Dweck: A Summary of the Two Mindsets and the Power of Believing That You Can Improve. Original graphic by Nigel Holmes. Copyright 2015 by Carol Dweck.

All of us—and all of our students—have elements of both fixed and growth mindsets. Various parts influence the attitude, such as the content area, issue, experience, historical success, and ambient conditions. For example, while you may normally have a mindset focused on progress when reading, encountering a book challenging for you to comprehend may evoke a perspective that is more fixed in nature. It does not exclusively fall.

Authors suggest educators reassess mindset treatments to specifically target kids at a high risk of academic failure and come from impoverished backgrounds, due to emerging evidence that general mindset interventions are not especially effective for many students. It is important to situate mindset treatments within the broader framework of worldwide social and emotional learning (SEL) initiatives. Teachers can help students cultivate a growth mindset by identifying the stimuli that prompt a transition from a growth to a fixed mentality, and pinpointing techniques they can employ to redirect their attention towards learning.

Perseverance and Grit

The authors cite the definition of perseverance and grit:

- Perseverance is primarily an internal construct that describes the willingness to stick with a challenge.

- Grit is an outward expression of this—how one shows persistence toward a goal, the ability to “give up a lot of other things to do it”, [demonstrating] deep commitments that you remain loyal to over many years” (Perkins-Gough & Duckworth, 2013, p. 16).

Authors point out two parts of perseverance and grit:

It is important for students to often come across both fictitious and actual people in their reading who show desirable attributes we hope students would consider and potentially embrace. Neli Beltran, a 3rd grade teacher, often selects titles for her daily “short book talk” that showcase people who exhibit resilience and determination. These book lectures provide the additional advantage of “blessing the book,” which involves the teacher endorsing and promoting specific titles, increasing their appeal to students (Marinak & Gambrell, 2016). Ms. Beltran delivers a concise summary, customizing her comments to align with her pupils’ preferences. Then she offers the book to anyone interested in reading it during the independent reading period that follows the book discussion. Her current preferences 2016. Ms. Beltran delivers a concise summary, customizing her comments to align with her pupils’ preferences. Then she offers the book to anyone interested in reading it during the independent reading period that ensues the book discussion. Her current preferences.

Another facet of endurance and tenacity involves identifying one’s passion and harnessing it to fuel one’s exertion. Youth scouting groups will help children and teenagers discover their interests through the implementation of a merit badge system. Those of us with experience in such organizations understand the drive that arises from adorning a ribbon with badges that symbolize our achievements. However, the key to these systems is their ability to motivate pupils to attempt tasks they may not have otherwise achieved. Adrienne Huston, a middle school English teacher, presented the computer game. The goals are to investigate various trajectories in life and to rescue children. “The level systems in these kinds of games are great for encouraging kids to take on harder tasks, but what seems to move them forward is earning badges,” she said. “In this game, there are badges called Lived a Good Life, Good Samaritan, Healer, and Lore Master. There are so many students playing it that we now have an informal after-school gaming club!”

Resiliency

Imagine this scenario given by the authors:

To stay on top of what his students face, Dominique logs his morning interactions with them. In a single day, before school had even started, he encountered students who were victims of child abuse, living in foster care, worried about getting kicked out. Faced with food insecurity and hoarding breakfast in the cafeteria.

- Stressing over an interaction with a boss at work the night before.

- Crying in the stairwell after a breakup with a girlfriend.

- Dealing with the death of a parent.

- Worrying about a failed test and needing a plan for academic recovery.

Authors state, “And these are just the students who decided to say something that morning. Imagine all the challenges students face in a given day. Imagine the ones they don’t tell us about. It’s impressive that they learn anything at all, given what else is on their minds.”

As educators, we can enhance the learning experience and outcomes for these students by recognizing the significance of social and emotional learning and focusing on the development of resilience.

Authors believe resiliency quizzes are useful in raising resiliency, identifying its parts, and developing plans to build or rebuild it. (This tool is intended for adolescents. For younger students, we recommend the PBS online tool featuring the animated character Arthur, at https://pbskids.org/arthur/health/resilience/quiz.html.) However, these quizzes do not increase students’ resilience.

The practical implementation is achieved through the integration of resilience lessons into our classrooms. Henderson (2013) used the term “safe-haven schools” to refer to schools that give high priority to this activity. Teachers in safe-haven schools implement strategies that foster resilience in individuals by cultivating pupils’ internal and environmental protective qualities.

Authors point out that it is important to develop students’ sense of agency and self-efficacy, so they have skills they can use when faced with a challenge. This can be as simple as selecting texts with resilient characters. The message in the classic story The Little Engine That Could is powerful for students, but it needs to be discussed. The point of the story is not about the train, but the effort that the train put forth to meet the goal. Older students might read Tupac Shakur’s poem, “The Rose That Grew from Concrete” (1999), for discussions about perseverance and resilience. When teacher Joel Perez shared the Tupac poem with his students, he asked them to identify the “concrete” in their lives and how they will break through that concrete to grow. One lesson on one text will not develop resiliency, but regular doses of texts that provide examples of strategies that can be used might change a life.

Authors’ Questions for Reflection

- What opportunities do you see in your content to integrate identity and agency into your practice?

- What techniques do you use to help your students recognize their strengths?

- What conversations do you have with your students regarding self-confidence?

- What techniques and language do you use to help students recalibrate their estimate of self-confidence when it is too low or too high?

- How do you integrate elements of self-efficacy into your content instruction? In what ways might your content be useful for building student beliefs about their efficacy?

- What is the current level of understanding in your grade level, department, or school about the nuances of mindset, beyond knowledge of fixed and growth mindsets? In what ways do your students learn about triggers that can shift them into a fixed mindset?

- Do you discuss resiliency with your students? What professional resources do you have in your school and district to help students who need further professional intervention due to trauma?

This blog is on Build Block of Social Emotional Learning You Need to Know