Effective Feedback

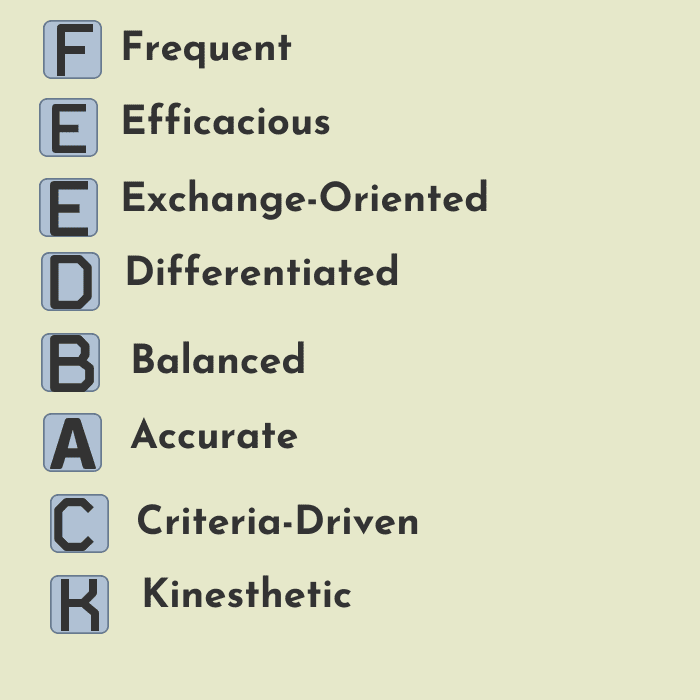

Effective feedback needs to be reviewed as just right, just in time, and just for me. It can nourish unprecedented growth in learning for all students. O’Connell and Vandas, authors of Partnering With Students Building Ownership of Learning, deconstructed feedback by synthesizing research and best practices into an easy acronym, using the word feedback itself. Authors explore each descriptor to deepen discussion of feedback and suggest ways to incorporate it into the classroom.

| F | E | E | D | B | A | C | K |

| Frequent | Efficacious | Exchange-Oriented | Differentiated | Balanced | Accurate | Criteria-Driven | Kinesthetic |

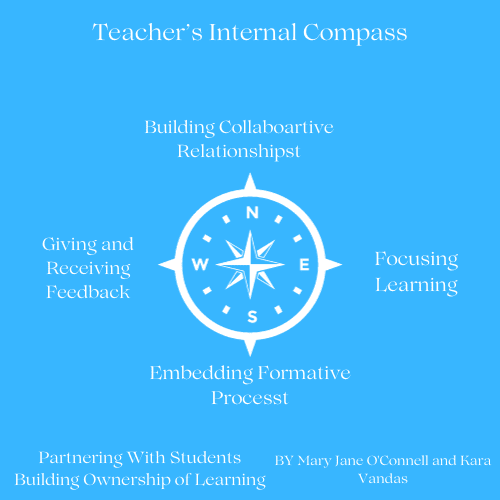

On the Teacher’s Internal Compass, we focus on the cardinal points South: Embedded Formative Assessments and West: Giving and Receiving Feedback, which enables teachers to receive direct feedback on how their instruction moves forward and whether to stay the course, adjust, or completely revamp instruction.

FREQUENT: Recurrent, Common, Every Day

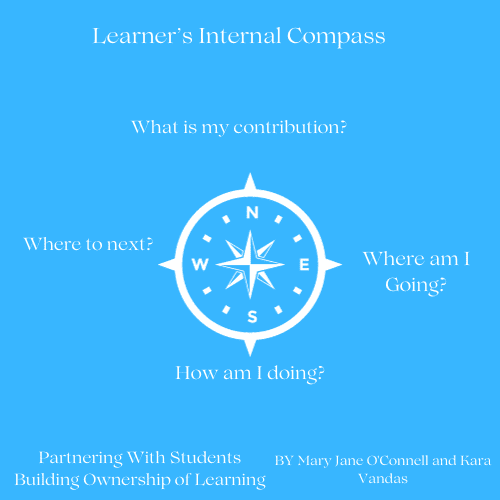

O’Connell and Vandas believe the timing and frequency of feedback are critical to informing and empowering students to take the next steps in learning. Feedback should answer the question Where am I going? How am I doing? and Where to Next? So, how often should feedback be offered or by whom?

A critical element in effective feedback, both immediate and delayed, is the quality of the instruction provided. Feedback can be effective if the instruction is meaningful, and provides students with enough information to move forward in their learning. (O’Connell and Vandas, 2015)

Immediate feedback is helpful when students learn a new idea or perform a task for the first time. Students need immediate feedback to provide accurate information about errors and misconceptions they have.

Delayed feedback is more effective when students have a sound foundation in a concept or skill. Students are working to deepen their learning. Writing process is a good example of delayed feedback. Authors want us to consider supporting students in achieving deep understanding, letting them grapple with learning to build skills as problem solvers, and understand the important process of persevering through challenges in learning.

Structures for Feedback: Immediate and Delayed

O’Connell and Vandas recommend teachers establish consistent and useful structures for giving and receiving immediate or delayed feedback. These structures can be done every day or week to ensure that lines of communication remain open, as the student demonstrates progress toward achieving the Learning Intentions.

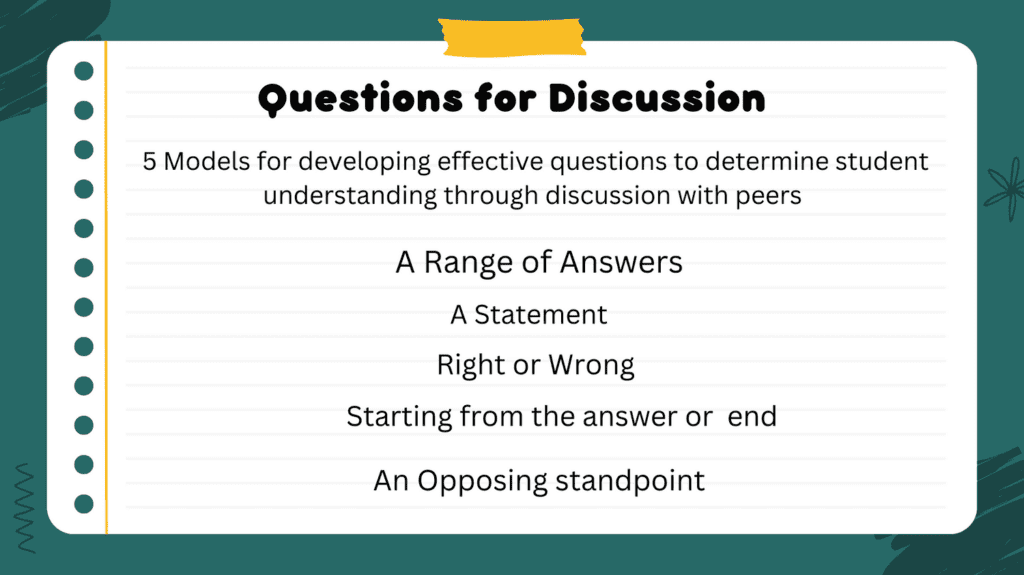

Five models for developing effective questions to determine student understanding through discussion with peers.

The Traffic Light

Traffic light is a structure that can be used daily at the end of the class for feedback, and it has many variations. The following is a sample of the questioning prompts:

Green — What I learned or Understand ——-

Yellow — What I am unclear on or sort of understand ——

Red — What I don’t understand ——–

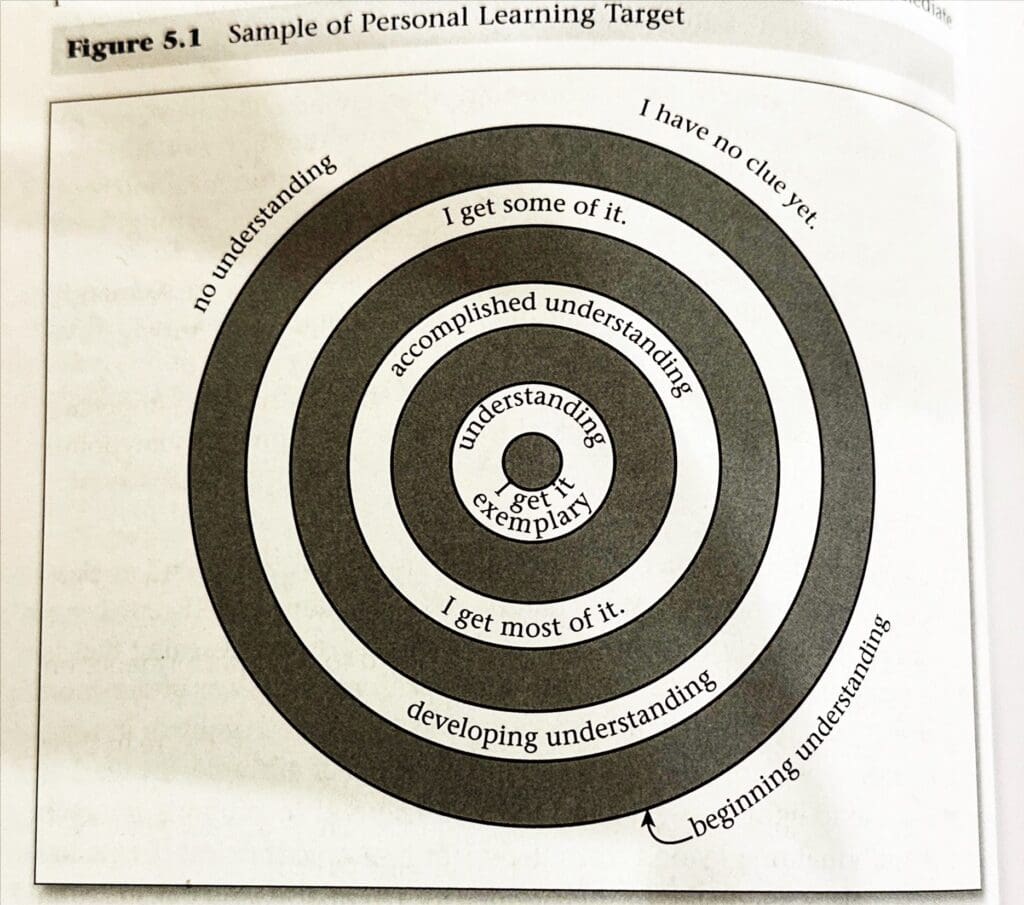

Personal Learning Target

Each student has a small target on his or her desk, and a game chip. For older students, the target could be posted in the room and provide a visual for a written or verbal exit slip. Students are asked to place the game chip on the target to represent how well they understand the Learning Intention. If they don’t understand, and need assistance or clarification immediately, they move the chip toward the outside ring of the target. If they understand and are progressing well, they leave the chip at the center of the target. This signals to the teacher and peers when a student needs help, and allows for targeted and immediate feedback.

Efficacious: Useful, Valuable, Successful

Students receive tons of feedback everyday. But how useful is the feedback? Authors want educators to consider two important points that relate to the word efficacious:

- Praise versus academic feedback

- Grades versus comments

Praise Versus Academic Feedback

Authors provide the following criteria for best practices around praise and academic feedback:

- Praise feedback, or feedback about the person, should be kept separate from academic or corrective feedback (i.e., “You are wonderful to have in class.”).

- Praise feedback should praise effort to relate to something the students can control, rather than intelligence (i.e., “The long hours and effort you expended are directly related to your performance on this exam”).

- Academic feedback should meet the students where they are in their learning progression (i.e., “I see you have used some dialogue in your writing. Let’s look at specific examples in our text to help you learn how to correctly format the dialogue”).

- When giving feedback, instead of providing students with the answer, scaffold the feedback so that they can answer a problem or question on their own (i.e., “I see you are trying to write your lab report. Please look at the Step 3 criteria and the example, and then revise this step to meet the expectations we discussed”).

Grades Versus Comments

O’Connell and Vandas emphasize that grades should be given only on work truly summative, or at the end of learning, after there has been ample time to practice the learning and receive feedback. Comments alone should be used on work that students will use to further their learning.

O’Connell and Vandas provide a student goals template that can replace grades with learning. Goal setting templates can also be called “contracts”. Authors believe they have positive effects on student ownership of learning, because they afford students the ability to

- Have greater control over what they are learning

- Receive targeted instruction from the teacher

- Work in groups with others with similar learning goals

- Focus on what matters most

- Better organize their time

- Give and receive feedback more effectively around personalized learning goals

| Name: Jamie, Grade 6 | Class/Period English Language Arts, Fourth Period |

| Learning Intentions Demonstrated on the Prestest – To explain how the plot moves a story along – To describe how the events affect characters to the story – To show how different parts of a story affect its meaning and the way the whole story turns out | My Personal Learning Goals – I need to work on reading the text to better understand how the events affect the main character, and how to explain that using examples from the story – I need to work on how different phrases and words the author uses affect the plot. I get how events affect the plot but never really thought about how the words the author uses make a difference. |

Another example authors provide is a learning portfolio. Building a learning portfolio with students’ help further transfer and connect what is being learned to the strategies being used to learn. It is meant to empower students to be owners of their learning, and also to facilitate partnering with others in learning. The goal is to inform students of the amazing strides they have made in learning, while simultaneously asking them to reflect on what empowered them to reach their goals.

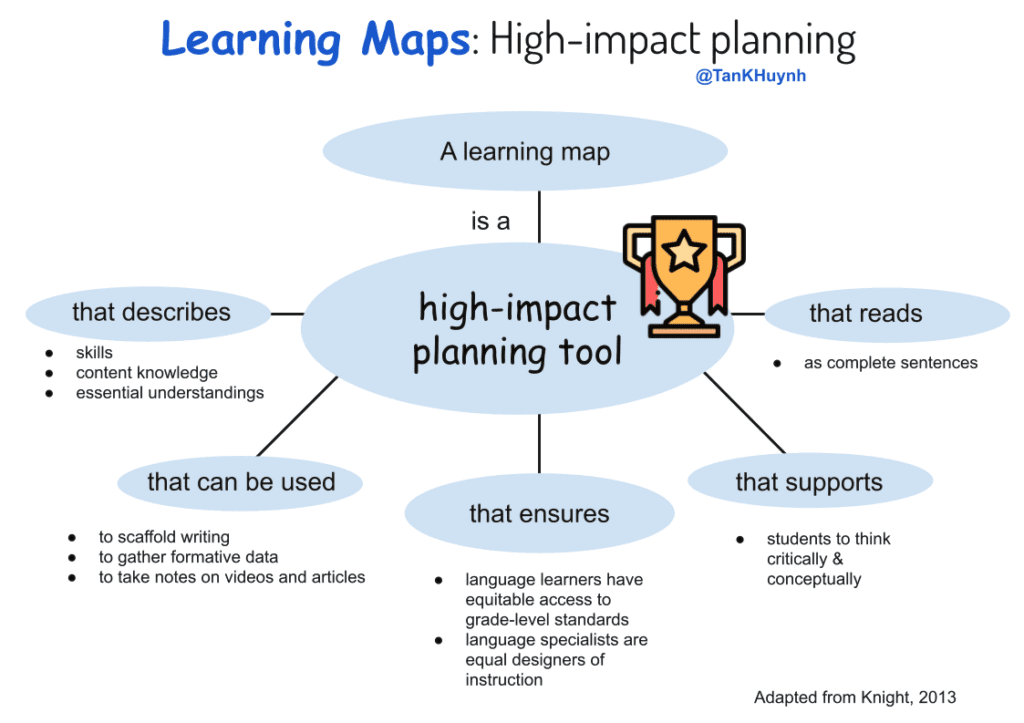

Authors suggest that as teachers and students work through a unit of study or a chunk of learning, we recommend collecting artifacts and using Learning Maps (Knight, 2013) to begin building the learning portfolio. The artifacts and Learning Maps will empower students to process and make connections about their learning, and later help them prove what they learned and how they learned it. Authors state “a distinguishing addition to the typical portfolio is the inclusion of a critical element: documenting Learner Strategies that are connected to the evidence of learning.”

The learning portfolio represents the journey of learning. O’Connell and Vandas suggest artifacts should include the student goals template, Learning Maps, work samples, homework, rough drafts, pre-assessments, journal entries, and any other representations of student understanding, knowledge, skills, and questions about learning. In addition to these forms of evidence, students should also include information about the strategies they have used as learners.

O’Connell and Vandas believe learning maps offer students a visual or graphic organizer, similar to a concept map, to depict the Learning Intentions. They can help students conceptually organize, visualize, and anticipate Where am I going? and also provide teachers and students with a vehicle to surface How am I doing? and where to next? Therefore, Learning Maps provide students with a concrete Learner Strategy to frame and organize their learning as they progress through the learning process.

The Learning Map may be included as a living, breathing part of the portfolio. It should begin with the most important ideas from a unit or chunk of learning, derived from the standards and Learning Intentions. When introducing a new unit of study, the teacher identifies essential learning for the unit, which could also include topics and subtopics. As the unit progresses, teachers and students regularly revisit the Learning Maps to record their growing understanding of concepts and topics. The map will allow students to connect ideas and break topics and subtopics into smaller parts, building a visual representation of their learning.

Have you considered how efficacious feedback could be if students offered comments about what did or didn’t work for them? Authors suggest students comment on how your modeling and use of a think aloud contributed to successful learning during group discussions. Now, you have useful feedback that informs you about your instructional practice and the effectiveness of group structures. When you act upon students’ feedback, it conveys the importance of the partnership and models how you value feedback from others.

Exchange-Oriented: Conversation, Interchange, Trading

When there is a feedback loop or two-way street in the teaching and learning process, it is implied in the exchange. Exchange depends on how feedback is given and received. Our goal is to deliver feedback appropriately, and acted upon, so learning moves forward. However, the feedback exchange can actually impede learning if it is misunderstood, ignored, or simply rejected.

O’Connell and Vandas illustrate how students can provide feedback to a teacher open to the exchange. Consider Maria’s story and think about how you might have responded.

Maria, a kindergarten teacher, was in the middle of a lesson when a little boy suddenly raised his hand and said he had no idea what she was talking about. She mentioned how it surprised her, but that she was glad he had stopped her to let her know. She then asked the class if they felt the same way, and explained what was confusing to them. She used their feedback to immediately adjust the manner in which she taught the Learning Intention. The information provided by this brave little kindergartner prompted Maria to reflect on future lessons she had planned and make improvements. While this sounds wonderful, think of alternative ways she might have reacted. She could have asked the student to listen better and not interrupt, or made some other remark to save face. However, her response demonstrated that she too is a learner. She modeled for her students how to take honest feedback and use it to learn and improve.

Authors recommend both modeling and offering frames or structures for feedback. Let’s look at an example, using a feedback technique called Two Wows and a Wish.

The structure requires two positive comments about a student’s work or performance, and one constructive criticism to improve on the work or performance. One way to model this structure is for a teacher to ask for feedback, and then model using the structure. For example, the teacher first provides instruction about how to write an argument. He then asks the students for feedback on the instruction, using Two Wows and a Wish. He thanks the students for their honest feedback and explains how he will use the feedback to change his instruction next time. After modeling how to use the structure to give and receive feedback, he provides the students with the opportunity to practice giving feedback on their rough drafts, using Two Wows and a Wish. To help students structure the feedback, he asks them to review a limited number of paragraphs to offer feedback, based on the Success Criteria and in the structure of Two Wows and a Wish. Students are then given the opportunity to share their feedback and improve their writing, based on the affirmations and suggestions offered.

Differentiated: Discerning, Set Apart, Individualized

O’Connell and Vandas emphasize the following:

- To be effective, feedback must be perceived as being personal and specific, and the timing must be appropriate for students to act upon the information. Students need to view feedback as “just for me,” “just right,” and “just in time.” This type of feedback captures what is described as the Goldilocks principle, and is a simple way to remember the necessary components of differentiated feedback.

- To have meaning and move learning forward, feedback must also be differentiated as students move through each of the cardinal points—North, East, South, and West—on the Learner’s Internal Compass. Feedback provides students with the prompts to respond to the questions. What is my contribution? Where am I going? How am I doing? and where to next?

Authors believe students who own their learning and are our partners share the responsibility for providing feedback to self and peers and acting upon the information. At surface level learning, students can check most of their work with answer keys, Success Criteria, or even by comparing responses with peers. The more difficult task is to empower students to recognize errors and rectify their misconceptions. O’Connell and Vandas provide examples of what the desired student response would be: “I got the same type of problems wrong, or I seem to make the same type of errors. I’m either being careless, or I don’t understand the concept and need to learn this again. I might first need to reread the text and examples and try the problems again. Maybe I’ll ask a classmate to explain it to me, or look at an online instructional video.

Interacting With Text: A “During Reading” Feedback Strategy

When students read, they often encounter words and phrases that interfere with their ability to understand or make meaning. The graphic organizer in Figure 5.3 can be used with students to document key ideas and issues they encounter as they read complex text. It would be best served in the later elementary grades and in middle and high school. As students read and make notes on the organizer, the teacher may circulate around the room, glancing at the responses to assess and intervene as needed to offer feedback, ask questions, clarify ideas, etc.

BALANCED: Learner to Teacher, Teacher to Learner, Peer to Peer, Self

To balance feedback and expand the results, teachers can adapt techniques within their existing routines at the beginning, middle, and end of lessons to provide opportunities for students to seek feedback from the following:

Self: Evaluating or using meta-cognitive strategies, seeking information or correctives, creating self-teaching or self-regulating situation.

Peers: Clarifying information or processing aloud for confirmation, peer teaching.

Teacher: Information gathering from interactions, questions designed to determine re-teaching needs, corrections to assignments, test and project evaluation (Pollock, 2012).

A strategy authors share is Teacher Feedback: Sharing Thinking through Sticky Notes:

A structure for teacher-to-student feedback involves having students generate their ideas on sticky notes while they read. Prior to independent reading, the teacher may define the types of ideas to include on the sticky notes. For example, if the class is working on character development, students may generate ideas about the attributes of the characters, changes in characters, or ways some characters interact with others to reveal the plot. As the teacher circulates around the room, he or she can review the notes students generate and offer feedback to deepen student thinking. To see this strategy in action, access the Edutopia video link to view “Making Sure They Are Learning” at www.corwin.com/partneringwithstudents.

Peer-to-Peer Feedback: Text PlaybackThis structure is done in pairs and involves retelling the main ideas and key details after reading a partner’s writing. This allows the writer to hear what the reader gained from reading his or her work. It can uncover misconceptions, areas the reader found particularly interesting, areas that lacked detail, and more (Fisher & Frey, 2011). The same concept can be applied to a common text students have read and tailored to meet specific Learning Intentions, such as discussing the author’s opinion and evidence or lack of evidence cited to support their claim.

ACCURATE: Progress in Learning, Feedback Fit

Authors use Hattie and Timperley (2007) as a simple but effective model for providing the right fit for feedback, depending on the cognitive complexity or rigor of the task. When the learning is new or students are introduced to the content for the first time, they are considered at the task, or surface level. The feedback that is most helpful is direct, immediate, and corrective. It is important to provide feedback that tells the student that he or she is doing the task correctly or incorrectly, and to address any misconceptions early in the learning process. It can be as simple as “yes, it is correct” or “no, it is incorrect.” Whether the response was correct or incorrect, it is often helpful to ask students to explain how they know the response is correct or what they need to do to ensure a correct response. If the students are completely confused or unable to provide an adequate explanation of how they arrived at a response, it may be best to reteach the concept.

As learners gain confidence in how to accomplish a task, the next layer of feedback required is at the process level. Process feedback guides students to make connections, develop deep understanding of concepts, process ideas and relationships to other ideas or concepts, and build strategies and routines.

As students progress to deep learning, they will reach the final feedback level, self-regulation. Students at this level can manipulate the task, apply various self-directed strategies, make decisions, and regulate their learning. Self-regulated learners can focus on the task at hand and monitor their own actions and behaviors. When confronted with additional information, they can consider what has worked in the past or design a completely new plan of action. In other words, self-regulated learners will push aside doubts and fears and take the first steps into unchartered new territory. They know they will learn from their mistakes along the way.

O’Connell and Vandas suggest Questions: Prompts for Providing Feedback: After thinking through each example, we suggest you try one of your own. Once you have determined the learning progression and Learning Intention you would like to address, develop questions for each feedback level that will prompt a student response to provide feedback at the task, process, or self-regulation level. If this is a new idea, consider trying your question prompts with only a few students to gauge their reactions to your questions and the feedback offered.

In addition to Questions: Prompts for Providing Feedback, authors provide Feedback Tracker Figure 5.5 provides a sample recording form to document the level of feedback provided to students as they respond to the question prompts. To use the Feedback Tracker for multiple days, use a different-colored pen each day and note the date. This way, it is clear if and when the feedback to students moved from surface to deep.

| Sample Prompts | Explain How Your Answer is Correct or Incorrect | What Strategies Did You Use? | How Could You Apply This to Another Situation? |

| Student Names | Task Level | Process level | Self-Regulation |

| Paul | (2/15) (2/17) | (2/20) | |

| Denae | (2/15) | (2/17) | (2/20) |

| Jaquan | (2/15) (2/17) | (2/20) |

CRITERIA-DRIVEN: Clarity, Alignment to Learning Intentions, Gauges/Drives Learning

Feedback is only useful when it pushes learning forward. Authors emphasize that feedback must answer the questions What is my contribution? Where am I going? How am I doing? and Where to next? Students receive a lot of feedback every day, but often it fails to address their progress toward achieving the Learning Intentions. The goal is to give feedback that addresses students’ progress.

Authors believe that when answering the four questions on the Learner’s Internal Compass, we must align the feedback to the level needed, based on where the student is performing and on the Success Criteria, to ensure quality academic feedback is given. Let’s take a few minutes to explore how these are connected, while reviewing a deeper explanation in Figure 5.6:

| Question | Answer | Explanation |

| What is my contribution? | The student response references Learner Beliefs and the class credo to monitor behavior and help others learn. | The student is self-regulated, but also demonstrates many learner beliefs. |

| Where am I going? | The student response references learning intentions, success criteria, and personal learning goals for the unit of study. | If students understand where the learning is headed, they must know and be committed to the learning intentions for the class, as well as their personalized goals. |

| How am I doing? | Teacher or peer feedback is aligned to success criteria and at each student’s level (task, process, and self-regulation). | Success criteria are essential to clarify what is required to meet the learning intention(s). The level of feedback can then be matched to a student’s performance level to best align to his or her needs. |

| Where to next? | Teacher or peer feedback aligned to learning intentions and success criteria, yet to be achieved, and at each student’s level (task, process, and self-regulation). | The student is guided to think deeply about what is learned, and to make connections and progress toward self-regulation to meet the learning intentions and success criteria. |

O’Connell and Vandas provide a strategy called Generating Criteria for Success: Educators generate a list of all the behaviors you would expect to see. You have just created a beginning list of what is needed for students to become criteria-driven and self-regulated. In other words, you have created the Success Criteria for students to truly benefit from criteria-driven feedback and also answer What is my contribution? Where am I going? How am I doing? Where to next? Now that you have gained greater clarity on the behaviors needed to provide effective feedback, you can engage your students in a similar activity that ultimately leads to improved work products and greater self-regulated learning.

KINESTHETIC: Action-Oriented, Answers Where to Next?

Authors emphasize that feedback must cause action—thus the word kinesthetic. If we employ all the elements of powerful feedback discussed so far, we still must ask ourselves, Is it working? Do I see my students making changes, deepening their learning, and asking more questions? Are the students reflecting on mistakes and engaging in further learning to ensure they can say “I’ve got it!”? Is the feedback impacting my instruction? How have I changed my instruction, incorporated students’ ideas, and developed more robust structures to facilitate feedback?

FEEDBACK to Self

Have you ever heard the phrase, “If it isn’t monitored, it won’t happen”? We want to become masters of effective feedback to best support learning for our students and ourselves. To do so, we must monitor our use of effective feedback practices. Use the FEEDBACK acronym under Summing Up: Learning Through Effective Feedback as Success Criteria to monitor your feedback practices. Think about a unit of study you recently taught. Look at each piece of Success Criteria to generate a concrete example that illustrates how you or your students demonstrated the criterion. Use the following questions to reflect on and consider potential changes in your practices:

What do you notice about yourself and the students?

Did you find an area where you excel, and maybe one in which it was difficult to generate an example?

What is the balance between the examples you generated for yourself and the examples from students? Is it balanced or out of balance?

What will you continue doing, and what might you consider changing?