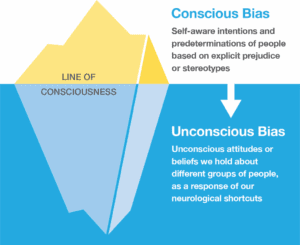

What is Unconscious Bias?

Unconscious bias is also called implicit bias—a type of social cognition that occurs below the surface, making it harder to detect as defined by Huda Essa, author of the book The Consciously Unbiased Educator.

Essa cites social scientists who believe unconscious bias can develop as early as age 3 (Flannery, 2015). They are often undetected and may even contradict a person’s pronounced beliefs. As a report from the Kirwan Institute (Staats et al., 2016) notes, “research from the neuro-, social and cognitive sciences show that hidden biases are distressingly pervasive, that they operate largely under the scope of human consciousness, and that they influence the ways in which we see and treat others, even when we are determined to be fair and objective” (p. 6).

Essa writes that overtime unconscious bias can become oblivious for each of us and it perpetuates “the admission of dangerous ignorance that gives rise to enduring negative influences.” (2024, pg. 9)

The truth about unconscious bias remains widely unknown and denied by large sections of society according to Essa. Unconscious bias exists in inequity of education system. As Essa points out, most teachers have been taught to do their jobs in a way that lets institutional oppression continue. The information, tools, and situations given to teachers don’t help promote cultural proficiency. Essa urges educators will continue to hurt students unless they learn to recognize and deal with their hidden biases. For all students, past, present, and future, we need to learn to see through the false ideas that our oppressive schooling taught us to think were real.

To get rid of hidden biases, teachers need to become culturally competent. Going after this goal can open your eyes and even change your life, but the road isn’t always straight and smooth. As Essa mapped out her own path to cultural proficiency, Essa had to face a flood of embarrassing realizations. Each added fuel to the fire of shame, making it impossible for Essa to safely move forward. Essa does not let the power of shame halt her progress. Essa realizes that her refusal to allow shame to slow her down turned out to be one of the best decisions of her life. Essa wants the same for you.

Essa emphasizes it’s important to recognize when shame is present. This can be hard, because shame changes forms. It could show up when we least expect it or aren’t ready to deal with it. Shame is often deep inside of us, but it controls many of the things we do on the outside. Please don’t take Essa’s warnings as a sign that she doesn’t believe you can grow. Essa wants to give you the tools and knowledge you need to become culturally competent quickly and easily.

Unconscious Bias Educators’ First Tool

Essa provides the first tool, as you learn, is an idea that you will need to remember: we were all born into systems of unfairness already in place. Essa reminds us of the mistakes you’ve made up to this point aren’t because you’re evil, but because of how you’ve been taught and conditioned.

Essa cites when shame hinders your progress, recognizing this frees your mind and heart to focus on the lessons happening right now. It also makes it easier to practice empathy, which experts now say is the most important leadership skill (Brower, 2021).

Preparing Your Journey: Creating Your Index

Essa explains an index you make will help you to keep track of what you are learning. Getting cultural proficiency is a personal goal that needs a tailored approach. As you read, you will have a wide range of feelings, thoughts, and reactions that require you to take a moment to pause and think.

First, get a notebook. This will be your constant companion and a key part of how you connect on this journey. You will make a system in your notebook based on Brené Brown’s “integration index” from 2022, which was based on Maria Popova’s “alternative indexing” method. Its job is to help you categorize and repeat what you are learning based on what helps you the most.

List the categories that are most important before you start making the index. Since you have the pen in your hand, make it your own. At any time, you can add or change categories. Write each item on your list as a heading on one or two pages of your notepad. Make sure there is enough room for your notes below each one. Here are examples of categories that could be used:

- “Aha” moments: New learning or information that excites or inspires you

- Vocabulary: Unfamiliar vocabulary words and definitions worth exploring or using

- Quotes: Quotations that resonate with you.

- Dig into later: Questions, things you don’t understand, ideas you want to research further and learn more about

- Put on hold: Concepts you need to put on hold for now. These might be ideas that challenge you beyond your current bandwidth — anything from a tired mind after a long day to emotionally charged reactions like shame and fear. It is OK to press pause, but this category is your promise to revisit the ideas, so you won’t have gaps in your foundational learning.

- Talk it over with: Ideas you want to share and discuss—for example, with colleagues at a meal, with loved ones on a call, with students in class, or with followers in a social media post.

- Take to work: Takeaways for timely application.

- Schedule it: Actions you don’t want to forget to take

- Personal connection: Ideas that ignite empathy on any level. This could directly relate to your life experiences or to those of significant others, including but not limited to ancestors, admired figures, family, and friends.

Essa suggests you can learn in the way that is most important with the help of the index. It tells you to take your time and figure out which ideas connect with you, even if they make you angry, excited, or confused. You can mark and highlight important ideas, and then write down the page number and any notes relevant under the index group that go with them.

Invitation to Connect and Converse

Essa offers another free key tool that involves conversation. Essa feels free and honest conversation is important to our cultural proficiency journey. Once again, Essa reminds us of shame rearing its ugly head. This time Essa calls it “Program Hush”. Program Hush, as Essa refers to, is the silence derived from disconnectedness between people, which leads to feelings of insecurity, inferiority (or superiority), uncertainty, inadequacy, stress, intimidation—even spite, anger, or apathy. Among all the people who you have disconnect with, the missing ingredient is empathy. Essa believes empathy is needed to generate the comfort necessary for authentic and productive discourse.

Essa provides another tool to help educators overcome program hush. Essa poses questions throughout her book that prompt you to reflect on a part of the information shared or how it applies to your life. Essa urges you to record your unadulterated, genuine responses in your notebook. Essa warns you that some of your responses may be sobering, but don’t you hold back. Essa suggests if you feel stuck on a challenging question, you can add it to a “Put on hold” section in your index, but you will need to revisit it at some point, so it’s best to complete as much as you can before moving on in the text.

Here are the pose questions by Essa for CONNECT AND CONVERSE:

- Think back to your childhood years. When did you first contemplate race, and what prompted this?

- What notions did you absorb about each racial identity? Some responses may be stereotypical or biased, but Essa urges you to honestly think about them anyway.

Essa urges you to hash out your own thoughts for each of the pose questions. Essa suggests using your voice to expand your knowledge base. This will give you practice at breaking the programmed hush instigated by shame. Essa notes by engaging in conversation here will infinitely enhance your experience off the page. You can then use your acquired skills in a way that compels others to do the same. It is important as you are expressing yourself and listening to your own voice. You will soon see why understanding what you think is the most effective action you can take.

My Attempt at Connect and Converse

When I started middle school in suburb of Buffalo, New York, I thought about race. Kids I don’t even know made fun of me because I look Asian. I was mad and didn’t understand what was going on. My sadness and insecurities were getting worse as I went through middle school and high school. I was 12 or 13 years old. It was already hard for me to learn English as a second language when I was six grade levels behind. I just felt cut off and by myself.

Put on hold: Notions I absorb about each racial identity.

Essa’s Childhood Experience with Race

Essa recalls her childhood experience with race in her own words:

Many of my own childhood memories are from Michigan in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Smartphones and online social media did not exist. Neighbors sat on their front porches and visited one another often. Kids played in the streets until sunset. We drank from hoses without a second thought and used them to spray unsuspecting siblings and friends during the humid summers. My memories include elaborate hairstyles, heavily trafficked sidewalks, and highlighter-bright colors.

However, this memory I’m thinking of includes simple hair and shades of dull brown: my neighbor Penny’s brown brick house, with its oak front door, coffee-colored mailbox, and wheat-brown stucco lining the front porch steps and columns. The sneaker-scuffed, drab brown tile on the floor stands out the most. The day my heart broke and my chin dropped, that floor is what I stared at through a curtain of brown hair I let fall to hide the tears stinging my chocolate-brown eyes.

Just moments before, we had been excitedly planning an epic sleepover at Penny’s. It would involve braiding each other’s hair, giggling over magazines, and eating buttered popcorn. With ear-to-ear smiles, Jill and I wiggled and hopped with excitement, waiting for Penny to return with her mother’s permission. We were sure the answer would be yes but were still eager to hear the joyful confirmation. The door swung open, and out came Penny skipping toward us. She enthusiastically announced to Jill that her mom had said yes! They swung their linked hands as they squealed and jumped up and down. As if on cue, Jill’s mother called to her from across the street to let her know that supper was ready.

I was stirring with excitement for my turn to celebrate with Penny as she watched Jill run home. After what seemed like a long time, she turned to face me, and her smile had disappeared. “Umm, Huda, we need to talk.” My bubbly friend’s voice had instantly trans-formed into an adult-like tone. She gently took my arm and walked me to the edge of the porch. Her eyes seemed to glance everywhere but my face as she mumbled, “My mom said you can’t sleep over.” Confused, I replied, “But you just told Jill that your mom said yes.” She took a deep breath, and this time, she looked straight at me to say, “My mom said that Jill can sleep over, but you can’t because you’re Black.” Confused again, I said, “I’m not Black, I’m Arab.” With a look of pity and a slight shake of her head, she said, “It’s the same thing.” I felt like I had been punched in the gut. My throat tightened and I turned my face toward the dusty brown floor. Now I couldn’t look at her. Heartbroken and filled with shame, I walked the short distance home. This was not the first time I had faced racial discrimination in my short years, but when it came from loved ones, it pierced through the thick skin I was rapidly growing to protect myself.

I could relate to Essa’s childhood memories. It reminded me of where I grew up in suburb of Buffalo from the late 1980s to early 1990s. I used to live in a ranch-style house in the shape of an L. There were neighbors on both sides of the street. There wasn’t much contact with neighbors. There were homes in the area built in the 1950s. The garage door and bathroom tiles in my house were both pink. I lived there with my parents and younger brother. The garage door and front door were painted red by my dad because red is thought to bring good luck. As a kid I rode my bike around the neighborhood often. I liked living in the suburbs when I was a kid. My neighborhood was peaceful and tall trees lined up on both side of the street.

I came to United States with my mom and brother in the 1970s. I vividly remember the encounter with a police officer my brother and I had. We were temporarily living with my uncle and aunt in the suburb of Chicago before moving to Buffalo to be with my father. It was during the day when kids were supposed to be in school. My brother and I had decided to ride bike around the neighborhood. We did not get far when the police officer stopped us. I told my brother to stay where he was, and I would get our mother to explain why my brother and I were not in school. It was scary since my brother, and I did not know how to speak English. Our cousins, David, and Howard, taught us the first word “dummy.”

My favorite show was Starsky and Hutch. I could not wait to watch the show every week. I even received magazine with Starsky and Hutch on the cover as a Christmas present from my parents. David Soul’s first album Don’t Give Up on Us was my first vinyl record I own along with a black and white record player I bought with my own money. The memories of watching the funeral procession of Elvis Presley on television and my first time going to a Tom Jones concert with my mom are something I will never forget.

Going into the job market as a computer programmer in the late 1980s, I had a hard time making it a career. I got married early in 1990 and moved to Long Island, New York. I learned hard lessons about life at this point as an adult. When things are hard and you feel like a failure, the most important thing to remember is to get back up and try again.

It breaks my heart to hear Essa talk about how hurt she was when her friend told her she couldn’t come over for a sleepover because she is black. I know how Essa must have felt because it made me think of how alone and sad I felt when I was made fun of because I looked Asian in middle school.

Look Back to Advance Forward

Essa reflects back on her childhood years where she describes as an adolescent, her family did not look like most families in her neighborhood. Essa first year of schooling it became painfully clear to her that her family and herself were not normal. Essa’s name was difficult for her teachers to pronounce. Essa’s parents were immigrants, and their English did not sound like most other parents. Essa knew then that she differed from her classmates. I understand why Essa felt she was different. But I disagree with Essa’s description of her family being not normal. Why is not normal? Because you have a different background or culture. Essa struggled with her identity when she was an adolescent, like I did. I changed my name to Maria, because I knew my Chinese name was hard to pronounce. I felt it was my fault for being Asian. Why can I fit in?

Essa felt the same way when she writes “One of the most profound psychological effects was an aching, continuously unfulfilled longing to fit into a mold that was not created for the likes of me.”

Review, Reflect, Resolve (3Rs)

To help educators to apply the knowledge reached to your everyday life, both in and out of the classroom, Essa provides one more tool: a set of three prompts designed to expand your understanding of the chapter. First, she asks you to simply review your perspective of the topic. To expand your understanding, you are then prompted to reflect more deeply on your experiences, beliefs, and relevant impacts. Lastly, you will resolve to immediately apply your learning toward improved practices and continual growth.

3Rs, as Essa refers to them, supply you with opportunities for contemplation and guidance for actions that move beyond your thoughts and into the real world. 3Rs help you build independent practice that will prove useful. Don’t forget to use your personal index to help you power through more productively!

Review

Think back to your childhood. Were you exposed to people, curricula, and media that offered you “mirrors, windows, and sliding doors” to diverse identities and perspectives?

When did you notice whether you shared the racial identity of leaders and figures you learned about in your curricula and most media sources?

Are you aware of whether your family history is like that of most others in the United States? Might it include instances of encountering prejudice or using tactics to avoid it that caused the loss of identities and valued cultural traits?

Reflect

What are advantages to young people seeing people who look like them in influential and positive roles?

How have your experiences with and among diverse populations shaped your worldview?

What obstacles have you faced due to limited knowledge of diverse identities (e.g. discomfort around discussing various topics, lack of confidence communicating with and learning from various identities, unhelpful and misplaced shame, or fear)?

Resolve

Consider the disadvantages you now have owing to discrimination your ancestors may have found. These may include loss of invaluable assets like languages, cultural traditions, family history, lessons, recipes, and communications, along with less direct disadvantages like poorly developed empathy.

Keep Learning