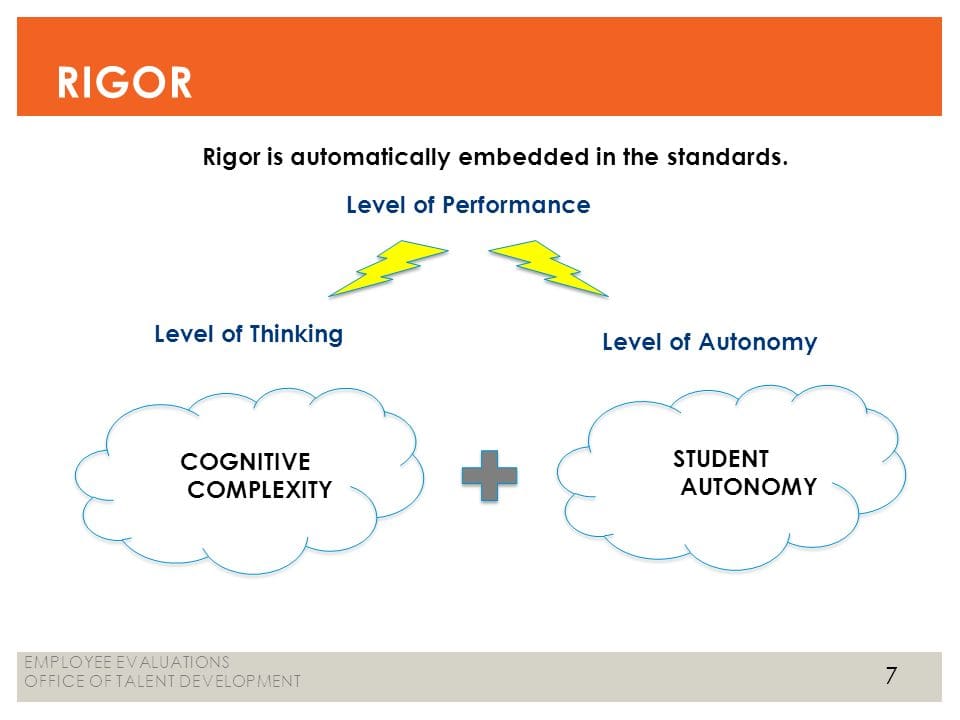

Two Key Components

Two Components in Path to Rigor

The Path to Rigor has two components-complexity and autonomy. This is according to authors Carla Moore, Michael D Toth, and Robert J Marzano, The Essentials for Standards-Driven Classrooms.

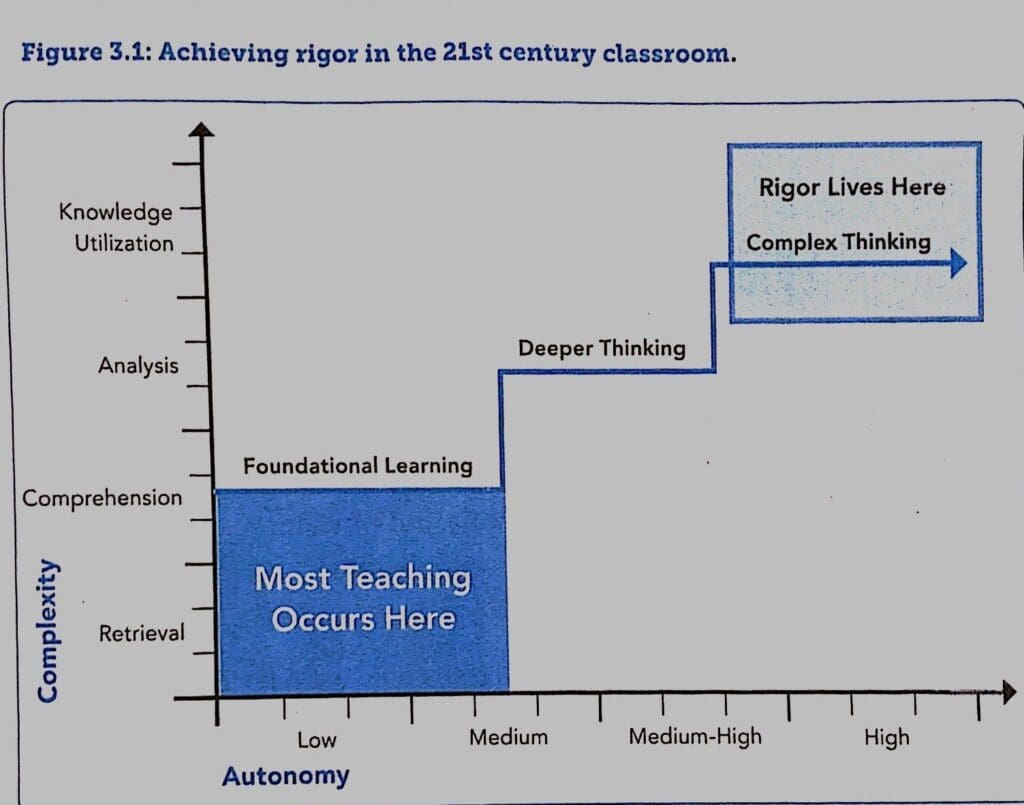

Complexity, authors define, is the cognitive load required by the standard. There are four levels in Marzano’s taxonomy: Retrieval, comprehension, analysis, and knowledge utilization.

Authors also describe four levels of student autonomy: low, medium, medium-high, and high. Most teaching occurs at low levels of complexity and autonomy, while the newest standards require high levels of both. Authors note there is still a gap between the standards and actual instructional practice. See Chart Below:

Complexity A Defining Feature of Rigor

Complexity refers to the cognitive demands of the tasks in which students are expected to engage. Authors show how to determine the complexity of a task you are designing by using Marzano Taxonomy. The taxonomy has two dimensions: complexity of the task itself and the content knowledge embedded in the task.

Carla Moore, Michael D Toth, and Robert J Marzano explain that by moving from the most complex to the least complex, the levels of complexity are knowledge usage, analysis, understanding, and retrieval. You can see this in the above chart.

Authors note each level involves many cognitive processes, i.e. retrieval (lowest level) involved recognition, recall and execution.

There are two types of knowledge: Declarative and Procedural.

Declarative is informational and has its own hierarchy in terms of complexity. Authors note that terms and phrases are important at the lowest level. Details are a level up, and the highest level are generalizations, principles, and ideas. According to Marzano, in his book Understanding Rigor in the Classroom, rigor regarding declarative knowledge is achieved after teachers identify specific topics on which they will focus. Rigor cannot be achieved with these topics or even a few topics simultaneously. Teachers must identify a specific topic or two on which to focus at their first order of business. See table below for list of Types of Topics for Declarative Knowledge:

| Topic | Examples |

| Specific people or type of person | Abraham Lincoln, US President |

| Specific organization or type of organizations | New York Yankees, Professional Baseball team |

| Specific intellectual or artistic product or type of intellectual or artistic product | Mono Lisa, famous painting |

| Specific occurring object or type of naturally occurring object | Linden tree, tree |

| Specific naturally occurring place or type of naturally occurring place | Artic Ocean, ocean |

| Specific animal or type of animal | Secretariat, famous racehorse |

| Specific manmade object or type of manmade object | Rolls-Royce, expensive passenger automobile |

| Specific Naturally occurring phenomenon or event or type of naturally occurring phenomenon or event | Mount St. Helens eruption, volcanic eruption |

| Specific manmade place or type of manmade place | Roman Colosseum, sport arena |

| Specific manmade phenomenon or event or type of manmade phenomenon or event | Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, holiday event |

| Specific manmade abstraction or type of abstraction | Linear function, function; love, emotion |

Before planning instruction to enhance rigor, a teacher should identify the specific declarative topics on which he or she will focus. With this level of focus established, the teacher can use various cognitive analysis processes to enhance rigor.

Using the Cognitive Analysis Processes

Marzano identifies five processes: Comparing, constructing support, analyzing errors, and elaborating. Marzano says these can be used virtually with all types of knowledge. However, some fit more readily with certain types of knowledge in certain situations.

Marzano gives an example of how the teacher design comparison tasks using the following process:

- The teacher identifies the topic to be compared.

- The teacher identifies simple characteristics on which to compare the topics.

- The teacher asks students to describe how the topics are similar and/or different.

- The teacher asks students to summarize what they have learned and describe how their thinking has changed.

You can find more information about the cognitive analysis processes in Understanding Rigor in the Classroom Chapter 1.

Procedural knowledge

Procedural knowledge involves generating something new according to Marzano’s Rigor in the Classroom book. For example, executing the procedure of adding numbers like 48, 78, and 3, you get a sum that was not explicit before the procedure was executed-in this case, 126. When you execute the procedure of writing a friendly letter, something new is produced-the letter to your friend.

Procedural knowledge is not as plentiful as declarative knowledge when it comes to the standards, but the procedures found in the standards are typically considered the centerpiece of their subject areas. The standards within history, for example, are overwhelmingly declarative, but few procedures like conducting a historical investigation are recommended within the history curriculum. Marzano provides Examples of Procedures within various subject areas below:

| Subject Area | Sample Procedural Knowledge |

| Mathematics | Solving linear equations |

| Language Arts Reading | Sounding out an unrecognized word while reading |

| Foreign Language | Using common idioms in informal conversation |

| Geography | Reading a contour map |

| Health | Employing a personal exercise routine |

| Physical Education | Throwing and catching a ball |

| Arts – Music | Playing the scale on a violin |

| Technology – Coding | Troubleshooting a set of code with errors |

Cognitive Analysis Processes

There are two cognitive analysis process that apply well to procedural knowledge to which students have already been introduced: Comparing and Classifying.

Comparing

The cognitive analysis process of comparing can enhance the rigor with which students execute procedural knowledge. The process involves the identification of increasingly more complex characteristics. The task design process includes the following:

- The teacher identifies the procedures to be compared.

- The teacher identifies simple characteristics on which to compare the procedures.

- The teacher asks students to describe how the procedures are similar and/or different.

- The teacher asks students to summarize what they have learned and how their thinking has changed.

Classifying

The cognitive analysis processes of classifying apply both to procedural knowledge and declarative knowledge.

Subordinate classifying involves identifying the various types of or categories within a given procedure. The task design process includes the following:

- The teacher identifies the procedure on which to focus.

- The teacher identifies the subcategories within the procedure.

- The teacher presents students with items that fit into the subcategories.

- The teacher asks students to sort the items into the identified subcategories.

- The teacher asks students to summarize what they have learned and describe how their thinking has changed.

Autonomy in the Classroom

Carla Moore, Michael D Toth, and Robert J Marzano believe teachers need to gradually release responsibility for learning to the students to achieve true cognitive complexity and autonomy – the intent of the standards.

Authors (2017) explain that students value reflection and learning when they have true autonomy and take initiative to learn more. The responsibility for learning must move from the teacher to students. Carla Moore, Michael D Toth, and Robert J Marzano emphasize this shift hinges on the teacher’s ability to shift from teacher-supported learning to peer-supported learning. “Students become self-guided and take control of their learning,” (pg. 45-46) written by authors. Students know when they have met their learning targets, and how to seek help when they struggle.

Authors (2017) believe there is a balance between teacher as coach who offers support and guidance, and teacher who asks guiding questions as facilitator. “The teacher monitors the temperature of the learning. Teachers know their students well enough to know how and when support and guidance might be needed.” (pg. 46)

Planning Instruction Important Part of Rigor

Rigor is important to planning, because taxonomy is the tool teachers must use to scaffold learning, from introducing new content at the foundational level to helping students deepen that content. The end goal is for students to reach higher levels of cognitive complexity with autonomy.

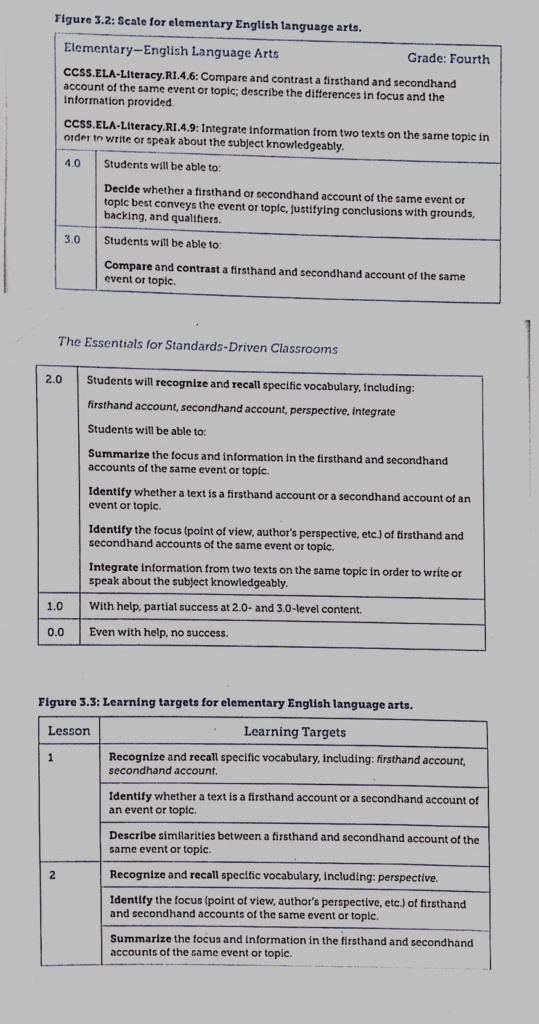

So far, authors have explained how students reach higher levels of cognitive complexity with autonomy. Now the focus is on performance scale. Carla Moore, Michael D Toth, and Robert J Marzano emphasize that the scale drives your planning, instruction, and the design and timing of your assessments. They believe The Essential Model maps the process to create a clear pathway to rigor for you and your students.

As you can see from The Essential Model above, Standards-Based Planning is discussed in my blog post Mastering Standard Based Planning Process. The focus now is on teachers’ work together to create common, standards-based scales for their lessons. Authors define performance scale as a continuum that articulates district levels of knowledge and skills relative to a specific standard. This will let teachers use minute by minute, day by day formative assessment strategies to track individual student progress and adjust and differentiate instruction. Plus, focus on feedback and celebrate learning progress when they have evidence.

Clustering Targets into Lessons

The key concept is that a cluster of targets will become your lesson plans. When clustering targets, we look for connections of ideas, or themes, between standards, often called strands. Then, we consider how to weave these learning strands for our students, while intentionally planning gradual release. Learning targets that will build foundations are the lower levels of complexity at level 2 on the scale. This is where building the academic vocabulary, connecting to previous learning, and building on the foundational learning by connecting to the higher levels of the scale, according to the authors.

In the Essential model, a lesson is not about span of time, but a chunk of content. Authors note it might take a day or two days. It is the target, or group of targets, that drives your lesson now. Figure 3.2 and Figure 3.3 This is another big shift in the way you think about a single lesson, according to the authors.

Authors note that the scale and clustering of targets for each lesson is sometimes as one target, and sometimes there are several targets. Teachers make these instructional decisions depending on cognitive demand and autonomy for that lesson.

Authors note the sequence of lessons builds from lower levels of taxonomy (level 2 of the scale) to the highest level of taxonomy (level 4 of the scale). At the same time, the teacher is planning for increased autonomy.

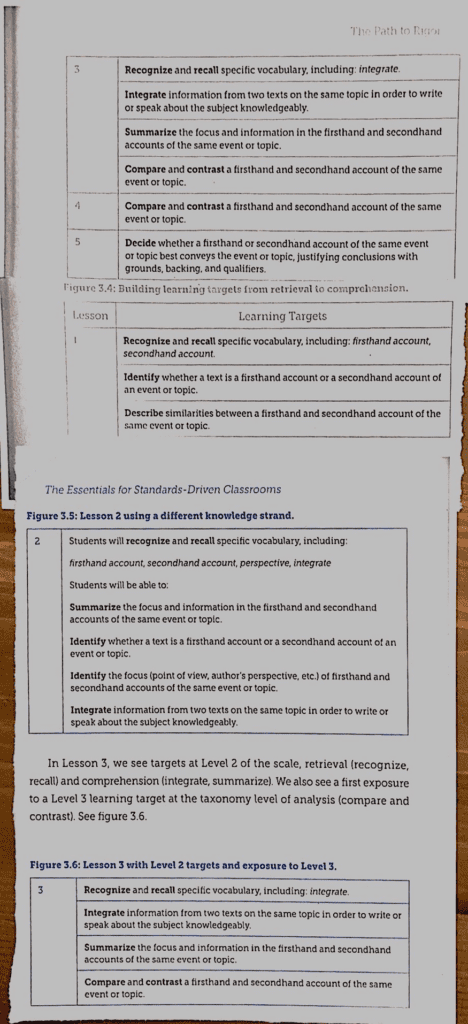

Lesson 1, from Fig. 3.4, has three targets that come from level 2 on the scale, but we can still see within the lesson a building of knowledge from retrieval (recognize, recall, execute) to understanding (describe).

You can see lesson 2, Fig. 3.5, follows the same pattern, but with a different strand of knowledge.

Lesson 3 is explained in the chart above.

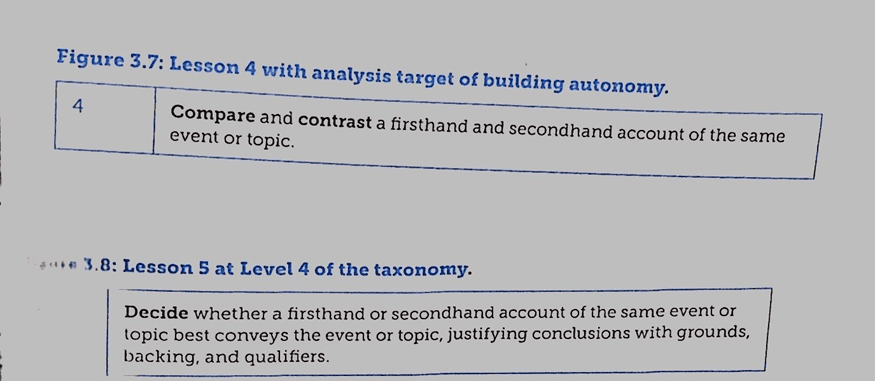

Bring the analysis back from the previous lessons to build autonomy in lesson 4. Lesson 5 takes students to level 4 of the scale at the taxonomy level of knowledge usage, where it brings all the learning together, from focus individual targets to the full intent of the standard where rigor lives.

Lesson Planning

Authors repeat that we are no longer planning lessons around an activity or chapter in a textbook. You are not starting with something for students to do, because when we start with activities, often we never entirely reach the standard. Authors (2017) note that the standards are driving the way we teach, and every lesson is designed to meet one or more learning targets. So, “By breaking down the standard into learning targets, and aligning instruction to the taxonomy, we can feel more confident in our students’ ability to achieve the intent of the standard.” (pg. 55)

Planning Instructional Strategies

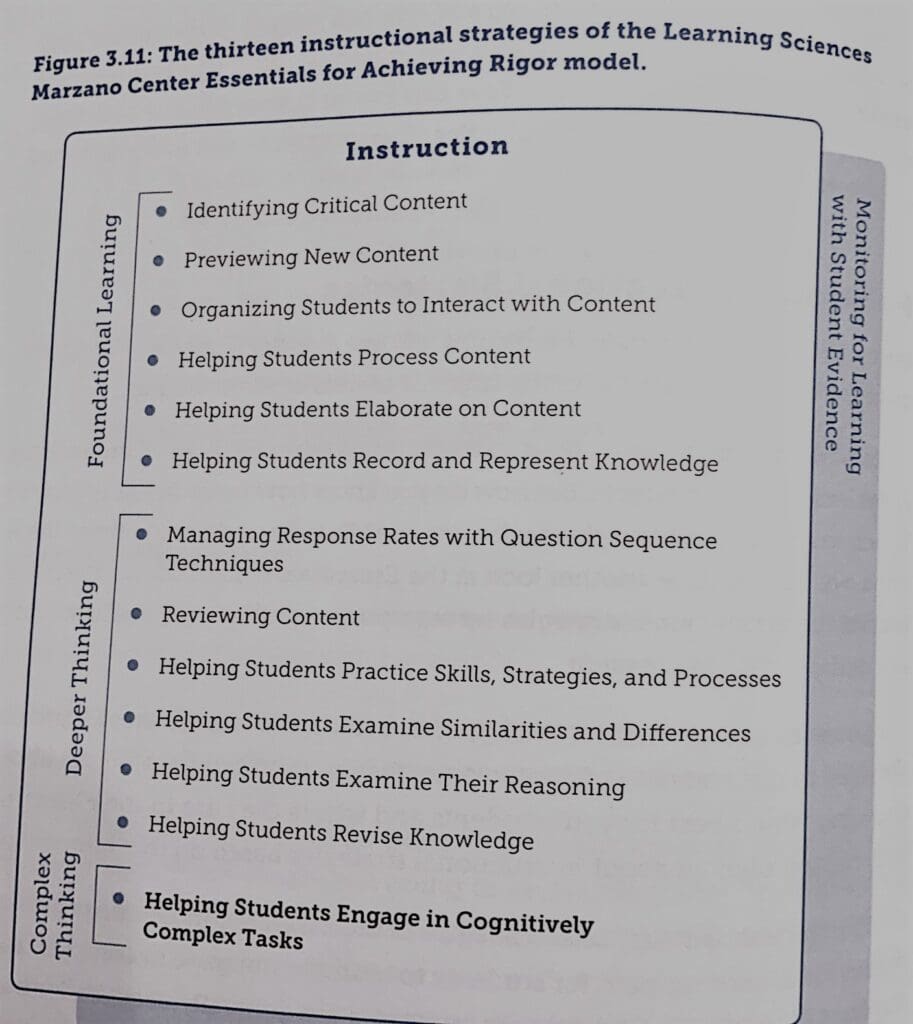

Carla Moore, Michael D Toth, and Robert J Marzano present the 13 Instructional Strategies in the Essential model, which provide a learning path for students to ultimately engage in complex tasks. According to the authors, the first six strategies are generally used for foundational learning or introducing new content. Authors note this learning is usually lower in complexity and includes the basic knowledge and processes that are more complex thinking is built on.

The next six strategies are applied to learning targets devoted to taking content previously learned and engaging students in deep thinking. Authors explain the purpose of the lessons for those learning targets is to have students think deeply about the content. These lessons require students to be analytical.

The final strategy is that students are thinking critically with full autonomy and knowledge usage level. However, authors emphasize that this depends on the taxonomy level of the standard.

Review

Marzano Resources provides a webinar A Guide to Standards-Based Learning. The webinar introduces key steps for transitioning to standards-based learning, and explains how teachers and leaders can leverage concrete tools to navigate the transition one step at a time. Viewers can expect to:

- Learn about the rationale for standards-based learning

- Understand how standards-based learning looks in hybrid, online, and in-person environments

- Discover tools that will help you successfully navigate the transition to standards-based learning

Conclusion

Carla Moore, Michael D Toth, and Robert J Marzano believe teachers will need to achieve classroom rigor. Teachers will need to plan instruction carefully, beginning with unpacking their standards and cluster learning targets on a scale aligned to the taxonomy. Once the scale is developed, it becomes the backbone of the teacher’s lesson plan. Teachers then create lessons using the instructional strategies suited to the targets and taxonomy levels of the targets. It is hard work, but you do not have to do it alone.

Reference

Moore, C., Toth, M. D., Marzano, R. J. (2017). The Essentials for Standards-Driven Classrooms A Practical Instructional Model for Every Student to Achieve Rigor, learningscience.com

Marzano Resources. A Guide to Standards-Based Learning https://mkt.marzanoresources.com/l/837863/2021-08-20/vrbx3