Rigor

Two Components on the Path to Rigor

Rigor is built on two connected elements: complexity and autonomy. According to Moore, Toth, and Marzano in The Essentials for Standards-Driven Classrooms, rigor increases when both cognitive demand and student independence rise together (Moore et al., 2017). For instance, high complexity with low autonomy may leave students struggling with advanced problems without the skills to manage their learning. In contrast, high autonomy without sufficient complexity can result in shallow activities. By linking these drivers, teachers can identify practical ways to balance both in daily planning, creating a more rigorous learning environment.

- Complexity refers to the mental effort required by a standard or task.

- Autonomy refers to the level of student responsibility for their own learning, ranging from low to high.

Many classrooms remain at low levels of both complexity and autonomy. A recent district survey found that only 30% of classroom tasks met the high standards for complexity and independence set by current educational guidelines. This gap between expectations and practice highlights the need for targeted improvements to raise standards.

Achieving Rigor

Complexity, a Defining Feature of Rigor

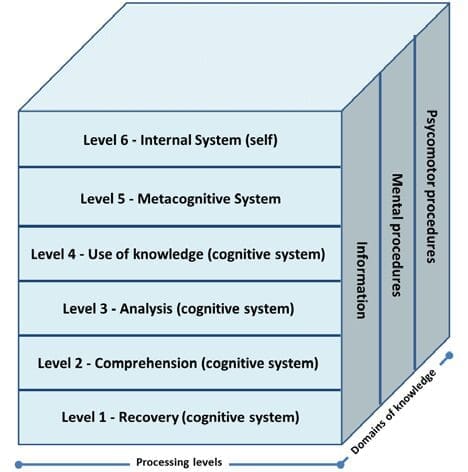

Complexity refers to the cognitive demands of tasks and assessments. Marzano’s Taxonomy helps teachers evaluate both task complexity and required content knowledge (Moore et al., n.d.). The taxonomy includes four levels: Retrieval, Comprehension, Analysis, and Knowledge Utilization (Marzano & J., 2001). Unlike Bloom’s or Webb’s frameworks, Marzano’s Taxonomy is closely aligned with standards-driven evaluation, providing a structured approach that matches current educational priorities and accurately assesses cognitive demands.

- Retrieval

- Comprehension

- Analysis

- Knowledge utilization

Each level involves specific mental processes. For example, retrieval includes recognition, recall, and execution. Reflect on your recent teaching: Which cognitive level was most common in last week’s assessments? This brief review can help you identify areas for further focus or improvement.

Two Types of Knowledge

Knowledge is categorized into two main types: declarative and procedural.

Declarative knowledge is information we know and are able to articulate.

Procedural knowledge is the set of processes we perform to create new outcomes or solve problems.

Declarative Knowledge

Declarative knowledge has its own hierarchy of complexity. The foundation is terms and phrases. For example, in a 4th-grade science class, students might begin with vocabulary such as ‘evaporation’ and ‘condensation.’ The next level includes details, such as how these processes contribute to the water cycle. The highest level involves generalizations, principles, and big ideas, like the principle of matter conservation. Marzano advises teachers to specify precise topics before increasing rigor, as focus is essential (Marzano & J., 2019). Covering too many topics can reduce depth and clarity.

Examples of declarative topics include:

- People or groups, Abraham Lincoln, U.S. President

- Organizations, such as the New York Yankees, a professional baseball team

- Artistic works, Mona Lisa, painting

- Natural objects, linden tree, tree

- Places, Arctic Ocean, ocean

- Animals, Secretariat, racehorse

- Manmade objects, Rolls-Royce, automobile

- Manmade events, Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, holiday event

- Abstract ideas, linear function, function, love, emotion

Once topics are clear, teachers can apply cognitive analysis processes to deepen learning.

Cognitive Analysis Processes for Declarative Knowledge

Marzano highlights five processes that can increase rigor across content types: Comparing, Classifying, Constructing support, Analyzing errors, and Elaborating (Marzano & J., n.d.). For novice readers, starting with Comparing is often the most straightforward approach. Adding a ‘start here’ note can help lower the barrier for initial classroom use.

Example, designing a comparison task:

- Identify the topics to compare. For instance, select a mathematical concept, such as solving linear equations, and a historical event like the signing of the Magna Carta.

- List basic characteristics for comparison. For linear equations, note the procedures and variables involved. For the Magna Carta, identify its historical context and key figures.

- Ask students to explain similarities and differences. For example, how do the steps in solving an equation compare with the regulatory and procedural aspects of drafting the Magna Carta? What variables and influences affected each context?

- Ask students to summarize what they learned and how their thinking changed. Encourage them to reflect on the analytical skills used in both mathematical and historical contexts, and how these skills can transfer to other disciplines.

Procedural Knowledge

Procedural knowledge involves a sequence of steps leading to a specific outcome. For example, solving 48 + 78 + 3 yields 129, and writing a friendly letter results in a complete letter. Emphasizing procedural fluency in the classroom is essential, as it supports efficient task completion and long-term knowledge retention (Mathematics, 2020). Balancing procedural and declarative knowledge creates a more comprehensive understanding that can be applied in various contexts, encouraging teachers to dedicate class time to this crucial area. While standards feature fewer procedures than facts or concepts, procedures often form the core of a discipline. For example, history contains many declarative standards, but procedural skills, such as conducting historical investigations, are also significant.

Examples of procedures:

- Mathematics, solving linear equations

- Language arts, sounding out an unfamiliar word

- World languages, use of common idioms in conversation

- Geography, reading a contour map

- Health, planning, and using a fitness routine

- Physical education, throwing and catching a ball

- Arts, Music, playing a scale on a violin

- Technology, Coding, and troubleshooting faulty code

Cognitive Analysis Processes for Procedural Knowledge

Two processes help when students already know the basic procedure:

Comparing procedures

- Before beginning this analysis, please make sure students can perform the procedure accurately three times in a row. This readiness helps prevent the analysis from starting too early.

- Identify the procedures to compare.

- List simple characteristics to compare. Ask students to describe similarities and differences.

- Ask students to summarize their learning and any shifts in their thinking.

Classifying within a procedure

- First, confirm students have mastered the procedure by having them perform it accurately three times. This step ensures they are ready for deeper analysis.

- Identify the target procedure. Identify subcategories within the procedure.

- Provide items that belong to the subcategories. Ask students to sort the items.

- Ask students to summarize learning and changes in thinking.

Autonomy in the Classroom

True rigor requires gradually shifting responsibility from the teacher to the students. Moore, Toth, and Marzano describe a progression from teacher-supported to peer-supported, then to self-directed learning (Moore et al., 2017). Students learn to monitor their progress, seek help when needed, and evaluate their work. Teachers should reflect on their current practices by asking, “Where do my students spend most of their time on this continuum?” This reflection helps map current autonomy levels and identify clear steps for improvement.

Teachers balance two roles:

- Coach, providing guidance and support when needed.

- Facilitator, using probing questions to prompt student thinking.

Strong relationships and regular checks for understanding help teachers decide when to provide support and when to allow independence. For background on student agency and autonomy, see

Student agency in classroom practice

What Is Learner Autonomy and How To Promote It

Planning With Rigor in Mind

Taxonomy guides scaffolding from foundational to deeper learning. The goal is for students to achieve higher complexity with greater autonomy. For example, you can use a quick exit slip at the end of a lesson. An exit slip aligned to a specific scale level can prompt students to reflect on their understanding by identifying the taxonomy level they believe they have reached. This frequent formative check allows teachers to adjust instruction based on student feedback. Performance scales help teachers plan, teach with clarity, and assess effectively.

A performance scale outlines the progression of knowledge and skills for a standard. It also supports frequent formative checks, responsive instruction, and timely feedback. For a practical overview of scales and standards-based planning, see:

Mastering Standards-Based Planning Process

Clustering Targets Into Lessons

A lesson is a cohesive unit of content, usually focused on specific learning targets and lasting one or several class periods. In contrast, a unit covers a broader topic over several weeks or months. Teachers group related learning targets into lessons, integrate targets across strands, plan for gradual release, and determine the cognitive demand and autonomy for each lesson.

- Early lessons target level 2 skills on the scale, build vocabulary, and connect to prior learning.

- Later lessons focus on analysis and the application of knowledge.

- Autonomy increases across the sequence.

- Some lessons may focus on one target. Others include several.

Progression example:

- In Lesson 1, students move within level 2 from retrieval to comprehension.

- Lesson 2, a similar pattern with a different strand.

- Lessons 3 and 4 bring back prior analysis and raise autonomy.

- Lesson 5, reach level 4, knowledge utilization, where students apply learning to the full intent of the standard.

Lesson Planning

Plan lessons around the standard and its targets, not just textbook chapters or isolated activities. Begin by drafting the level-4 assessment task, then scaffold backward. Break the standard into clear learning targets and align instruction and assessment to the taxonomy. This approach increases the likelihood that students meet or exceed the standard’s intent. For a primer on clear learning targets, see:

How to Align Learning Targets to Standards in a Simple and Repeatable Way

Planning Instructional Strategies

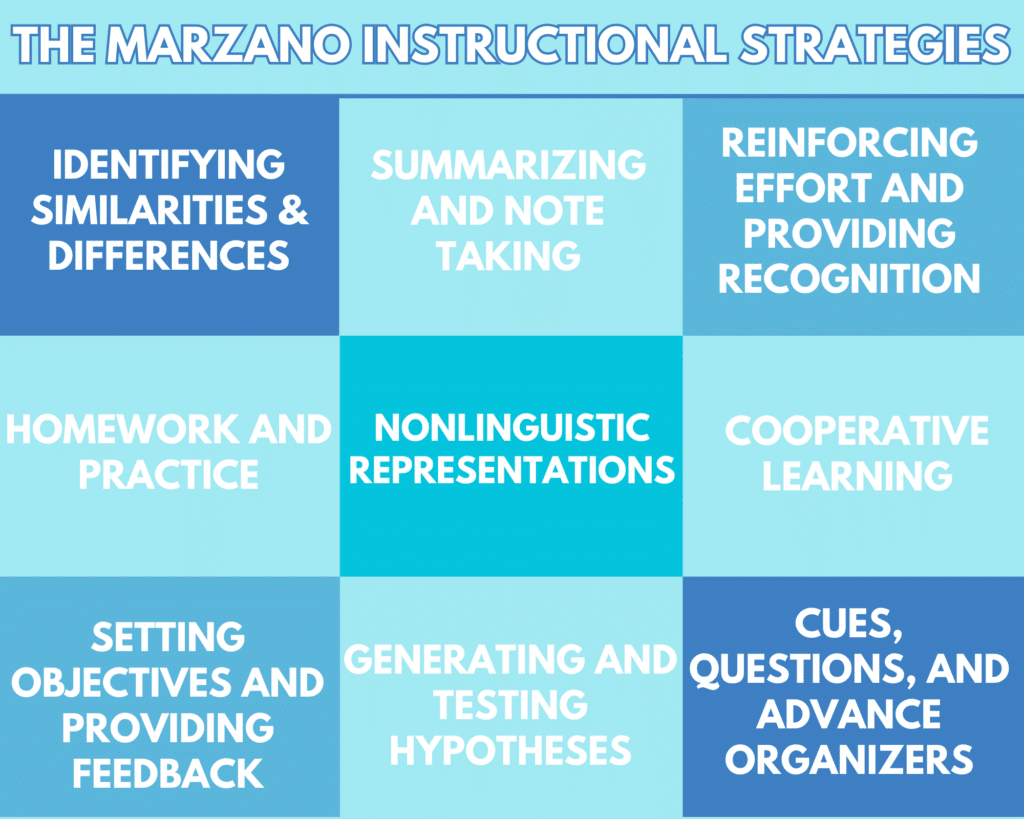

Moore, Toth, and Marzano present 13 strategies in the Essential model to guide students from foundational understanding to deep thinking and independent application (Moore et al., 2017). For example, consider teaching the concept of photosynthesis.

In the foundational phase, teachers introduce basic terms and simple processes of photosynthesis, focusing on key vocabulary such as ‘photosynthesis’, ‘chlorophyll’, ‘sunlight’, and ‘carbon dioxide’.

As the lesson progresses, students engage in reasoning and analysis, such as discussing how different light intensities affect the rate of photosynthesis. They may support their findings with experimental evidence or use error analysis to understand data variance.

For full autonomy, students apply their understanding of photosynthesis in a practical, complex task. For example, they might design a small-scale experiment to test how plants adapt to different environments, demonstrating independent application with minimal guidance.

- Introduce new content.

- Build terms, details, and simple processes.

- Maintain tasks at a lower complexity while ensuring accuracy.

Strategies for deep thinking

- Engage students in analysis and reasoning.

- Ask for explanations, support, and error analysis.

- Move tasks into higher complexity.

Strategy for full autonomy and knowledge use

- Students apply learning in complex tasks with minimal support.

- Autonomy depends on the target’s taxonomy level.

For related tools, see:

Marzano Resources webinar, A Guide to Standards-Based Learning:

Great Schools Partnership on performance scales and proficiency:

Conclusion

Building rigor requires intentionally increasing both complexity and autonomy. Start by unpacking standards and identifying specific learning targets. Place targets on a clear performance scale linked to the taxonomy. Cluster targets into lessons, plan for gradual release, and select strategies that match the required complexity. Use frequent formative checks to adjust instruction, provide feedback, and celebrate growth. Collaboration with colleagues supports sustainable progress. This week, try one new strategy from this guide and discuss your results with a colleague. Let this step bring theory into practice.

Reference

Moore, C., Toth, M. D., & J., R. (2017). The Essentials for Standards-Driven Classrooms: A Practical Instructional Model for Every Student to Achieve Rigor. Learning Sciences International. https://www.deslegte.com/the-essentials-forstandards-driven-classrooms-4716052/

Moore, Toth, C., Marzano, M. D., & J., R. (n.d.). Two Key Components in the Path to Rigor in the Classroom. educationblogdesk.com. https://educationblogdesk.com/two-key-components-in-path-to-rigor-in-theclassroom/embrace-powerful-learning-approaches/what-students-should-know-common-core-standards/

Rico, M. (2013). Figure #-1. Marzano’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. www.researchgate.net. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Figure-1-Marzanos-Taxonomy-of-Educational-Objectives_fig1_248400457

Mathematics, N. C. (2020). Procedural Fluency in Mathematics. Position Statement. https://www.nctm.org/Standards-andPositions/Position-Statements/Procedural-Fluency-in-Mathematics/

Moore, C., Toth, M. D., & J., R. (2017). The Essentials for Standards-Driven Classrooms: A Practical Instructional Model for Every Student to Achieve Rigor. Learning Sciences International. https://store.instructionalempowerment.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/esdc_lookinside.pdf

Moore, Toth, C., Marzano, M. & J., R. (2017). The Essentials for Standards-Driven Classrooms: A Practical Instructional Model for Every Student to Achieve Rigor. Learning Sciences International. https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/theessentials-for-standards-driven-classrooms-carla-moore/1125505961

Heflebower, T. (2021, August 5). A guide to standards-based learning (EDWEBINAR). A Guide to Standards-Based Learning. https://mkt.marzanoresources.com/l/837863/2021-08-20/vrbx3

Proficiency-based learning: A roadmap for educators. Great Schools Partnership. (n.d.). https://www.greatschoolspartnership.org/proficiency-based-learning/