Introduction

The shift in classroom atmosphere from grade-focused to reflective learners is illustrated by a 7th-grade class. Initially, students waited outside on “test pass-back day” focused only on their grades. A year later, they began by reviewing tracking sheets and discussing skills before even receiving tests, shifting emphasis from teacher judgment to student reflection.

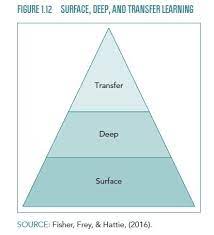

The shift toward assessment-capable learners was achieved not by extra homework or harder tests, but by fostering rigor that develops critical thinking, explanation of reasoning, and learning decisions. Rigor means combining challenge and support. Assessment-capable learners monitor progress and plan next steps while the agency acts on these insights. When rigor and agency combine, students advance through stages: Rigor, Student Agency, Surface Learning, Deep Learning, and Transformation Learning. This guide interprets “Rigor Reimagined: A Pathway to Learner Agency” and offers actionable classroom steps.

Professor Hatti on Assessment of Capable Learners Video

Refer to the Home Page section under How Integration Works Between Each Component: Rigor and Student Agency

What Does Academic Rigor Really Mean Today?

Misconceptions about rigor, such as equating it with extra work or fast-paced instruction that only benefits the strongest students, still persist and can harm learners.

Today, academic rigor prioritizes “thinking work” over “busy work.” Assigning many repetitive problems does not ensure rigor, but using a smaller set of thoughtfully chosen, challenging problems fosters deeper reasoning—even with less paper.

Researchers such as John Hattie and others in the Visible Learning field link rigor to clear purpose, active thinking, and effective feedback. (Hattie & Clarke, 2018) For more on assessment-capable learners, see the article ” Demystifying John Hattie’s assessment-capable learners.“

Genuine rigor has three parts that work together:

- Clear, understandable goals

- Challenging tasks that match those goals

- Support that helps every student reach them

This rigor-centered approach advances student agency. When students understand the “why” of a challenge, they feel empowered. Such an approach also promotes growth from basic knowledge (surface learning) to deeper reasoning (deep learning) and transformative identity shifts (transformation learning).

Rigor Reimagined: High Expectations With Smart Support

“Rigor Reimagined: A Pathway to Learner Agency” is based on a simple idea: maintain high expectations for every student and provide support that gradually decreases as students gain independence. Rigor is not a barrier; it is a ladder students learn to climb on their own.

In literacy, consider two tasks based on a shared text. Task A requires students to copy vocabulary definitions and answer recall questions. Task B asks students to select a key idea from the text, find supporting evidence, and write a brief explanation in their own words. Task B is more rigorous because it requires decision-making, evidence connection, and original expression.

In math, a low-rigor assignment might involve 20 practice problems using the same procedure. A more rigorous task would have students solve 6 increasingly complex problems, then compare two methods and explain which is more efficient and why.

This perspective on rigor emphasizes equity: every student deserves appropriately challenging tasks. Scaffolds support students as they begin challenging work and gradually fade as students become more independent in learning and decisionmaking.

You can read a deeper treatment of this view of rigor in Rigor Reimagined: A Pathway to Learner Agency.

The Goldilocks Level of Challenge That Grows Confidence

Effective challenge balances difficulty. Tasks that are too easy bore; those that are too hard discourage. The right challenge supports student growth.

With the right level of challenge, students may say, “This is hard, but I think I can get it if I try a different way.” They view struggle as informative, using errors to guide their next steps rather than as fixed judgments about ability.

When a challenge sits in this zone, learning speeds up. When challenges are appropriately matched, learning accelerates. Students pay closer attention to feedback and are more willing to compare their work to models and success criteria, making adjustments as needed. Over time, they learn to identify their own optimal level of challenge by asking, “What is the next step that is hard enough to help me grow?” Is this mindset central to assessment-capable behavior?

Assessment-capable learners approach assessment as an ongoing process for understanding current progress, setting goals, and planning next steps.

In Hattie’s work, these learners have a strong effect on achievement. (Waack, 2018) A clear explanation appears in the ASCD article, Developing ‘Assessment Capable’ Learners. In student-friendly terms, assessment-capable learners:

- Know what success looks like in their current unit.

- Can place their own work on a learning continuum

- Use feedback, data, and reflection to adjust their approach.

Rigor matters because it shifts focus from struggle to insight. Students who track their learning strategically respond to challenges, not by guessing or giving up.

In this context, rigor serves as a mirror. Challenging assignments reveal specific areas for growth. Students who interpret these reflections are more likely to address learning gaps. Over time, they become less dependent on teachers and external grades, developing their own standards and goals.

Key Traits of Assessment-Capable Learners in Rigorous Classrooms

In rigorous classrooms, assessment-capable learners tend to exhibit a common set of traits. They might sound like this:

- They know their current level. “Right now I can solve one-step equations, but I mix up the steps on two-step problems.”

- They name clear goals. “Today I want to focus on checking my answer with inverse operations.”

- They choose strategies that fit the task. “For this text, I am going to annotate the margins instead of using sticky notes.”

- They seek feedback. “Can you look at my explanation and tell me if my evidence matches my claim?”

- They use mistakes as data. “I lost points on explaining my reasoning, so I will add a sentence frame to my notebook.”

- They teach others. “Let me show you how I used the model to set up this problem.”

Rigor links directly to these traits: simple tasks stifle strategic thinking, while challenging work reveals thinking and growth opportunities. Resources on visible learners, such as Developing Capable Visible Learners, offer more classroom-friendly language.

How Rigor, Student Agency, and Self-Assessment Work Together

Rigor, agency, and self-assessment form a continuous cycle, with each element reinforcing the others as students advance. A rigorous task highlights students’ strengths and areas for growth. Agency is demonstrated when students decide how to respond, such as by trying new strategies or seeking feedback.

Self-assessment supports these decisions. Students compare their work to success criteria, peer examples, or previous attempts, then plan next steps. Accurate self-judgment leads to greater achievement. Hattie’s meta-analyses show a strong effect for students who do this with precision. (Hattie, 2009) If a classroom emphasizes rigor without agency, students may feel pushed and powerless. If agency is praised without challenge, students may feel confident but remain at a surface level of understanding. The greatest impact occurs when both are present: demanding work and learners equipped to respond.

From Surface to Deep to Transformation Learning Through Rigor

Rigor supports a learning journey that begins with basic knowledge, advances to deeper understanding, and can lead to transformative insight. Hattie and others describe this progression as moving from surface learning to deep learning, and then to transfer or transformation. A summary of these stages appears in Visible Learning: Surface, Deep, and Transfer.

Surface learning is not negative; it is the stage where students acquire words, facts, and basic skills. Deep learning connects these elements, while transformation learning changes how students view a topic or themselves. Rigor is present at each stage, though it takes different forms.

Consider the current and desired depth of tasks within a unit. This evaluation can reveal why some units feel less effective, even if they are busy.

Getting Surface Learning Right Without Getting Stuck There

Surface learning provides the foundation. Students must read words, recall dates, identify shapes, and follow single-step procedures. The key is how they engage with this content.

Rigorous surface work does not stop at copying from the board. It might include:

- Short retrieval practice where students recall key ideas from memory

- Quick “explain your answer” prompts, even on basic items

- Sorting activities where students classify examples and non-examples

Assessment-capable learners view surface checks as valuable feedback. For example, a student might mark a yellow “traffic light” on a vocabulary quiz, then choose to create flashcards and retest in two days.

Teachers can encourage this habit using tools such as exit tickets, one-minute writes, or brief self-rating scales. When students recognize that these checks guide future learning rather than serve as punishment, they engage more fully in the process.

Using Rigor to Move Into Deep Learning and Real Understanding

Deep learning begins when students connect ideas and ask questions such as, “Why does this work?” or “How does this relate to previous learning?” At this stage, rigor arises from cognitive demands rather than the length of assignments.

In ELA, deep learning may involve students comparing two characters’ responses to a challenge, using quotes as evidence, and discussing how culture or setting influences those responses. They move beyond retelling to analysis and justification.

In science, deep learning may involve designing an investigation to test the effect of a single variable on plant growth. Students determine what to control, predict outcomes, and justify their experimental design.

Rigor grows as students respond to prompts such as “Convince a skeptic,” “Find the flaw in this argument,” or “Explain why this method works better in this situation.” A helpful discussion of balancing surface and deep tasks appears in Finding the Balance of Surface and Deep Learning.

At this stage, student agency expands. Learners may select sources, choose appropriate graphic organizers, or decide how to demonstrate understanding. Self-assessment includes questions such as, “Did I explain my reasoning clearly?” or “Does my evidence support my claim?”

Reaching Transformation Learning and Strong Student Agency

Transformation learning extends further. Here, content not only informs but also changes how students view an issue, other groups, or their own potential.

In social studies, students might study local housing policies and present proposals to the city council on fair access, leading some to see themselves as advocates rather than just test-takers. In STEM, students may design water filters for local homes experiencing water quality issues, with success measured by real-world impact and lab reports.

At this level, rigor is found in open-ended problems, authentic audiences, and self-established standards. Students co-create rubrics, define quality, and reflect on both product and process. Many educators, including those at Empower Student Ownership of Learning in the Classroom, associate this stage with strong agency.

Assessment-capable learners engaged in transformation tasks ask questions such as, “Whose voices are missing from our research?” and “How will we know if our solution helped?” They view themselves as learners who can act, measure, and improve.

Practical Moves to Build Assessment-Capable Learners With Rigorous Tasks

Theory is valuable only when it informs classroom practice. Fortunately, small, clear actions can connect rigor to assessmentcapable behavior without requiring a complete curriculum redesign.

Consider these as levers to use within your current units. Select one area, implement it for a week or two, and gather student feedback.

Clarify Learning Goals and Success Criteria in Student-Friendly Language

Students cannot self-assess or exercise agency if goals are vague or written in technical language. Begin by rewriting standards in student-friendly terms.

For Example:

- Standard: “Analyze how a theme is developed over the course of a text.”

- Student-friendly: “I can explain how a big idea grows from the start to the end of the story.”

- Standard: “Solve multi-step real-world problems using proportional relationships.”

- Student-friendly: “I can break down a word problem into steps and use ratios to solve it.”

Convert these into “I can” checklists for students to revisit throughout the lesson:

- Before: “Which parts of this goal already feel green for you?”

- During: “Pause and check one box, which part are you using right now?”

- After: “Where would you place yourself on this goal today, and why?”

A prompt such as “Where are you now on this goal?” encourages students to provide evidence rather than rely on feelings. Over time, these daily check-ins help students develop assessment skills.

Use Feedback, Errors, and Reflection to Grow Agency

Feedback in rigorous classrooms focuses on the task and process. Instead of saying, “You are smart” or “You are wrong,” use statements like, “This part meets the goal because…” or “This step is missing, so your answer does not match the problem.” Treat errors as data. For example, say, “This mistake shows the second step is not yet secure. Which support would help you practice that step?” Students can then choose from options such as a worked example, a peer tutor, or a short video. Simple reflection routines help students translate feedback into action:

- A quick write: “One strength in my work today is…, one thing I will adjust next time is…”

- Traffic-light ratings: Students mark a goal red, yellow, or green, then explain why.

- Before-and-after samples: Students keep a “first draft” and “final draft” side by side and label the changes.

Each routine supports rigor by focusing on the quality of thinking rather than mere completion. Over time, students begin to seek this type of feedback and reflection independently, indicating growth in assessment capability.

Conclusion

Rigor, student agency, and the progression from surface learning to deep understanding and transformation form a coherent path toward assessment-capable learners. When rigor is viewed as a thoughtful challenge with gradually reduced support, classrooms become both demanding and supportive. Students learn to interpret struggle as feedback rather than failure and develop greater accuracy in assessing their own progress. This shift changes classroom conversations from “What grade did I get?” to “What does my work show and what will I try next?” The next step does not need to be large. Choose one change, such as clarifying goals or introducing a new reflection routine, and test it with your students. As students take greater ownership of their progress, the rigor of your tasks will feel more meaningful, and learners will rise to meet it.

References

Hattie, J. & Clarke, S. (2018). Visible Learning: Feedback. Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780429485480/visible-learning-feedback-john-hattie-shirley-clarke

Waack, S. (2018). Collective Teacher Efficacy (CTE) according to John Hattie. Visible Learning. https://visiblelearning.org/2018/03/collective-teacher-efficacy-hattie/

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Visible-Learning-A-Synthesis-of-Over-800-Meta-Analyses-Relating-toAchievement/Hattie/p/book/9780415476188