Collaborative Relationships for Learning

Improving Students’ Relationships with Teachers to Provide Essential Supports for Learning

In their book, Partnering with Students, authors Mary O’Connell and Kara Vandas provide strategies for better collaborative relationships of learning.

Collaborative relationships for learning are the first step in building ownership of learning with students as partners. Today, students need to prepare to set goals, to fail, to get up and try a new strategy, to fail again, and to persist until their goals are realized. So, are all students in our classrooms equipped with the skills and confidence to take ownership of their learning? What can we do for students who are not prepared?

Authors emphasize we must examine our beliefs about empowering students to own their learning. Here are questions to consider:

How can relationships impede or catapult learning?

How do I establish a classroom where learning is a partnership?

Examine Our Beliefs

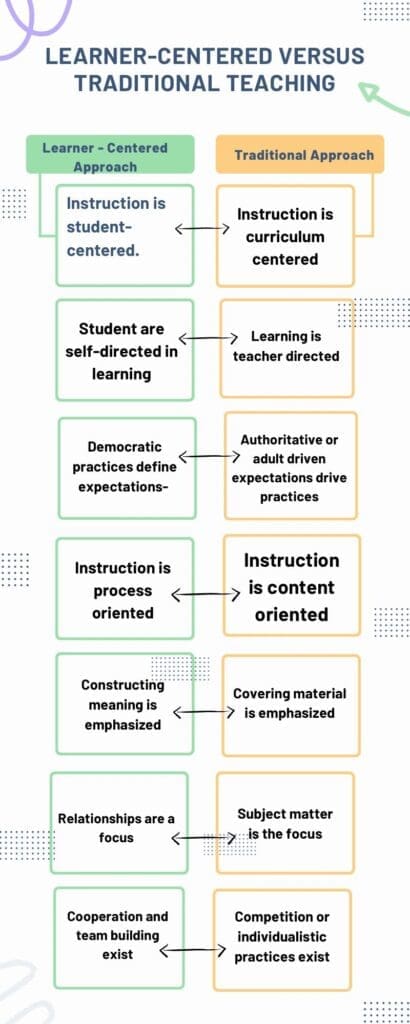

O’Connell and Vandas invite educators to begin examining beliefs and practices by reviewing the descriptions used to broadly differentiate a learner-centered approach and traditional teaching.

Authors ask to imagine you are a first-time visitor to your school and classroom. Authors encourage you to step out of yourself and listen and look anew at the surroundings as you meander through the hallways and enter a few classrooms. What do you hear and see that suggests there is evidence of a learner-centered approach or a traditional approach from the above list. In the middle column, please place a check mark on the continuum to show what you believe most typically occurs in the classrooms you visited. Afterwards, check your beliefs about your own classroom.

Invite Students to be Partners in Learning

O’Connell and Vandas urges you to invite students to be partners in learning once we have examined our beliefs about students and learning. According to O’Connell and Vandas, the focus here is to talk about students making decisions, crafting a classroom belief system, engaging in discussions about what worked and didn’t in class, and letting the power be shared in a partnership model. Authors want to shift the focus from seeing students’ deficits to relying on their strengths, so we can establish the relationships that propel us forward as partners in learning.

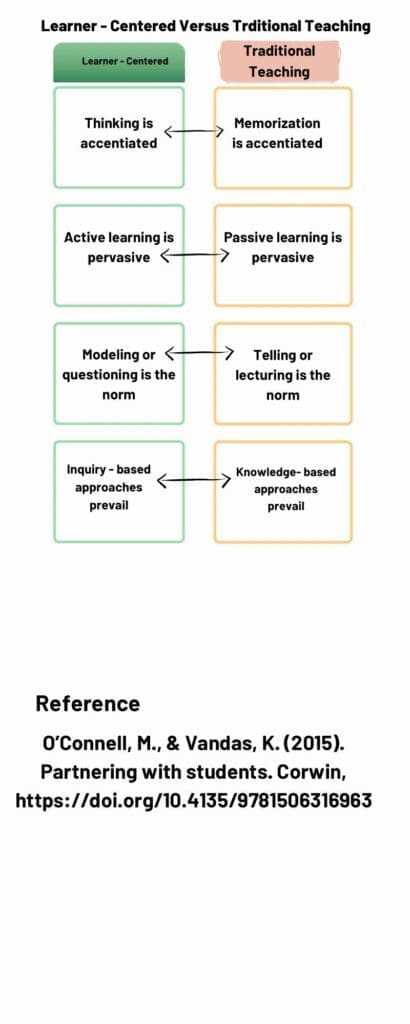

You may ask how I do this in my classroom. I want to build stronger relationships. I want my students to believe in themselves as learners. But how? Where is the road map that guides me on my journey? O’Connell and Vandas developed the TRUST Model to provide a framework of actionable steps and essential parts supported by research to establish students as active partners in learning.

The TRUST model may seem different from elementary to secondary classrooms in practices and procedures, but the model provides a framework for teachers to establish students as partners in learning. Authors encourage teachers to develop authentic interactions with students in the areas highlighted within the TRUST model. I will show strategies associated with TRUST model authors provided in their book.

Strategies for Better Collaborative Relationships of Learning (TRUST Model)

Talent

Beliefs That Influence Learning

Ask students to write about their experiences as learners or what they know about themselves as learners. You might consider the following questions to get their ideas flowing:

What makes a good or competent learner?

What does a learner do when confused or stuck?

How can classmates/peers help our learning?

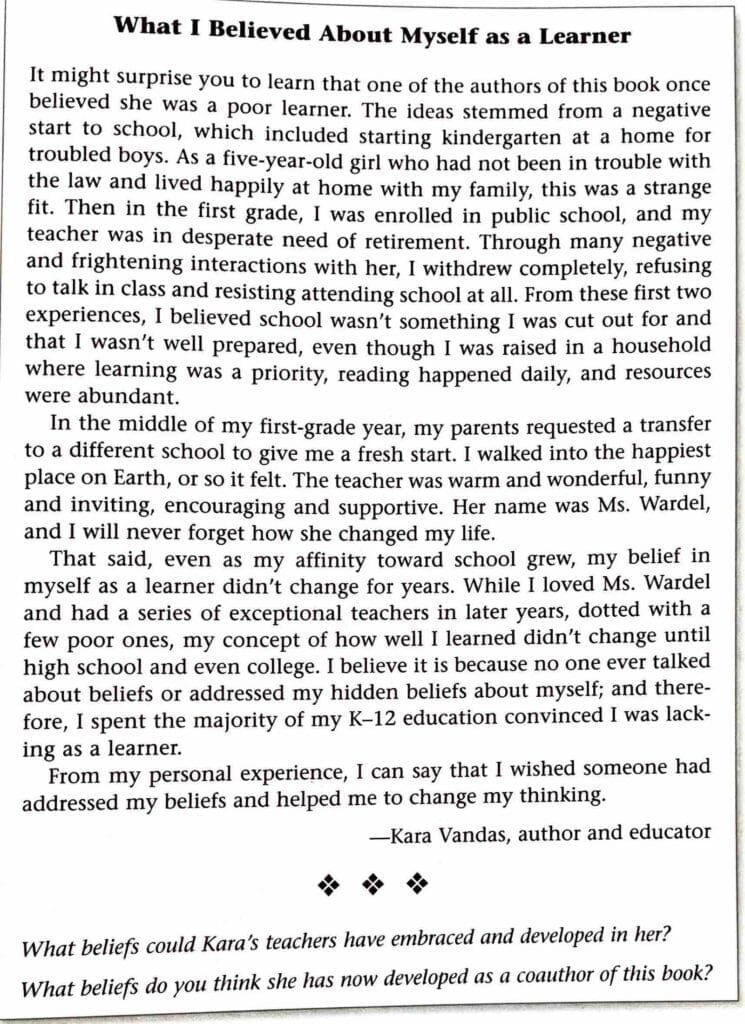

To introduce your students to the writing assignment, share and discuss the beliefs this author had about herself as a learner:

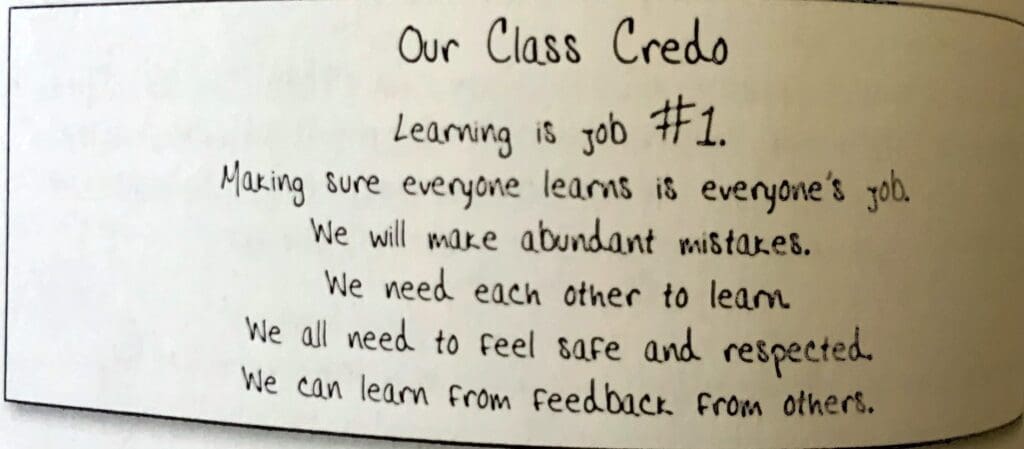

Developing a Class Credo

The Class Credo is a set of agreed upon beliefs about learning that support collaboration, reflection, risk-taking, and other important elements embedded in the Learner Beliefs. It is a living document and can be established. Credo documents should be revised, as learning experiences shape beliefs during the year. The document recognizes the role of every class member and the effect of his or her contributions. Credo captures the evolving, agree-upon beliefs of what it means to be part of a collaborative, learning community.

You can develop a class credo by asking students to list their strengths as learners. Start by asking students to make two lists in response to two questions:

What makes a good learner?

What makes a good classmate who contributes to your learning?

Authors recommend these lists can become a launching point for a discussion to develop a class credo to promote learning. Here is an example:

Rapport + Responsiveness

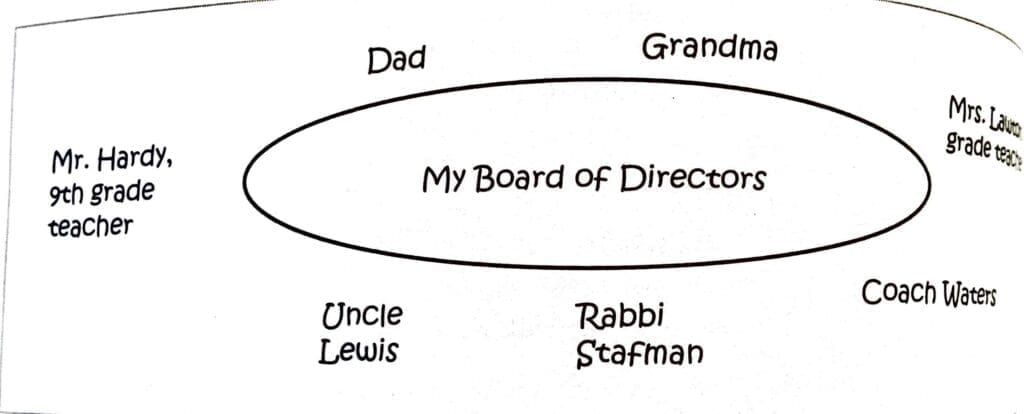

Board of Directors

Ask students to think about the people who have been most influential in their lives by providing support and direction. This is to help students consider how they have developed their beliefs and what is important. A Board of Directors is elected to help manage the life of a business. Authors suggest to think of people who sit on our own Board of directors. Ask students to identify the people who have built rapport, modeled responsiveness, and affected their life positively.

Students can then draw a Board of Directors table and write each person’s name and role (parent, sibling, teacher, clergy member, friend, etc.). Students might interview, share in groups, or write about these influential people and how they have affected their lives. As students share their experiences, connect to the Learner Beliefs, and build relationships through rapport + responsiveness.

Here is an example:

Mistakes as Opportunities to Teach and Learn

Model and share how you handle mistakes, errors, and misconceptions as opportunities to learn. When students perform poorly on classwork or on a test, accept responsibility for not teaching the material as effectively as you might have, and share this admission with your students. Ask for their ideas on how to improve the lesson. You are only human.

Begin an “oops!” chart or a “mistakes and misconceptions” chart: I thought I knew… but I didn’t. This is what I did to learn… Invite students to share and chart their experiences, along with your mistakes and insights.

“Us” Factor

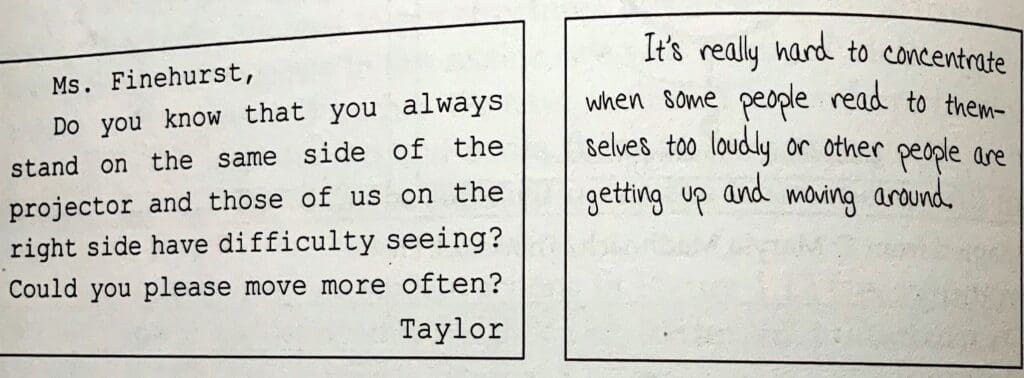

Issue Bin or Parking Lot

Authors encourage you to provide a way for students to surface issues affecting learning or to suggest improving the classroom environment, learning, and even your teaching. Here are simple ways:

Mount a piece of chart paper

Provide a space on a bulletin board

Offer a comment box for students.

Post something on a sticky note

Teacher then screens the notes and decides which submissions can be discussed as a class to generate possible solutions and those that must be addressed individually. It may be frightening to share issues directly related to your own performance, but you can discuss issues with students if they include their name with what they shared. Authors emphasize that by being vulnerable and openly sharing your students’ concerns, you are modeling an important life lesson: how to accept and act on feedback that is less than desirable. You are giving students a voice in their classroom and recognizing that they are important stakeholders.

Some examples of student-generated issues:

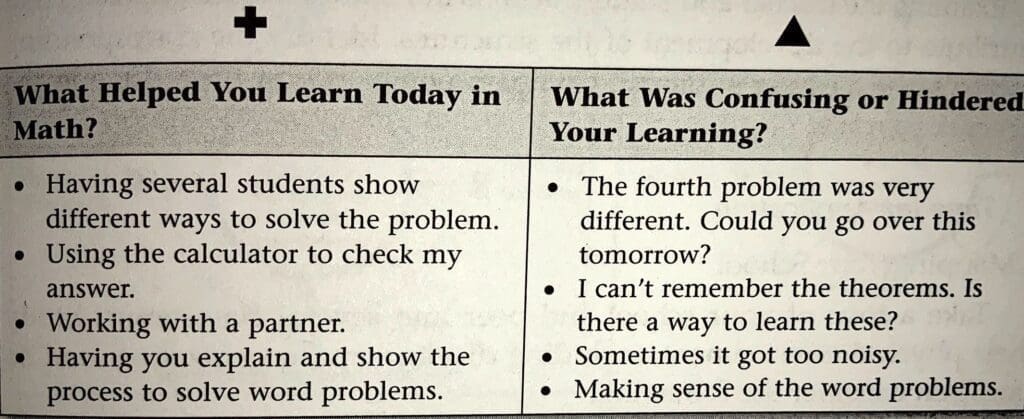

Plus/Delta

Authors suggest spending 3 to 5 minutes at the end of the class to discuss with students about the things that happened in class today that moved their learning forward (pluses) and the things that could help them learn more effectively (delta: the Greek symbol that connotes changes). You can create a T-chart on the chart paper to record the pluses on one side and the delta on the other. As a teacher, you can share how you will address the issues within your control.

Classroom example of Plus/Delta Chart:

If students showed they needed more examples or practice opportunities with you before doing independent work, students can offer ideas how this might look tomorrow. Ask students to suggest what they could do tomorrow to move the deltas to pluses. The following day, direct students to the pluses and deltas discussed, recall the suggestions for improvement, and make a commitment. You can ask students to do a quick write describing how they will address a delta to improve the learning environment. After the period, conduct another plus/delta, and you should see most deltas move to the plus side. Call attention to the Learner Beliefs being evidenced.

Structures

Mapping Your School

Tour your school and peer into several classrooms. Study their physical environment, including displays and organization, etc. Then consider:

Which rooms would you predict encourage and promote student collaboration?

Besides the physical arrangement, are there any charts or other visuals that describe expectations or procedures for group work?

How does your room compare?

What should you do if you want to structure a classroom conducive to collaboration and partnering with students?

Look Who’s Talking

To get a sense of the balance between teacher and student talk, consider timing yourself to see how much you talk and how much your students talk among themselves. Track the time for at least a week. Consider asking one of your students to keep track of the time and chart it for you. If you are serious about partnering with your students, share the information with the students and ask for their help. Once you determine the percentage of time you are talking, set a goal to reduce it and chart it for all to see. Imagine using a plus/delta to discuss the benefits of more student talk time, and how the time be used more productively for different strategies, questioning prompts, or activities. Your students will have lots of ideas. If you conduct an internet search and enter teacher talk, you will be rewarded with a multitude of ideas.

Time

Writing Is Thinking

Authors suggest taking the time for you and your students to create a journal or reflection log to chronicle the journey. Provide time for students to discuss the changes in their Learner Beliefs and practices, because they promote greater collaboration, partnerships, and learning.

Providing Learning

Authors encourage teachers and students to gather evidence of learning, find achievement gains, and document effective learning strategies.

Conclusion

Authors suggest that educators take the time to think about potential changes in your beliefs and theories of practice as you begin to navigate the exercises in the TRUST Model. Take some time to reflect and plan:

How can relationships impede or catapult learning?

How do I establish a classroom where learning is a partnership?